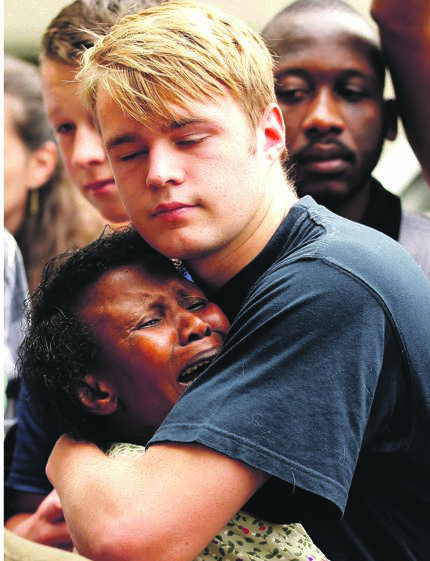

In our deeply racialised society transitioning from ingrained habits is slowly evolving in the quest for nonracial forms of social cohesion, write Njabulo Ndebele, Crain Soudien,Gerhard Maré and Nina Jablonski

Opportunities to apply one’s undivided attention to a serious social problem, especially in academe, are rare and worth seizing.

In 2012, a number of us, led by professors Nina Jablonski and Gerhard Maré, were given the opportunity by the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (Stias) to think about the question of race and racism in the context of what it means to be human in the world today.

Responding to the imperatives of our location, our minds were naturally seized by the summons of being human in South Africa.

The broad aim of what we called the Effects of Race (EoR) project was to understand better the effects that race and racism in the past 500 years of world history have had on our capacity to be full human beings.

Stias gave us three years to develop the project.

It also enabled us to bring on board four groups of scholars who were working on the related issues of how the ideas of race were developed and how they were learnt and unlearnt in the environments of the school and the university within the broader society.

The EoR project members met annually for two to three weeks each year at Stias’ home, the Wallenberg Centre, from 2015 to 2017, and again for a brief period this year.

We engaged in a deliberately slow dialogue on what we knew about race and racism, including how these notions came to be and how they function and are upheld in contemporary society.

For a few short weeks in successive Cape winters, the EoR project created a fire of ideas.

The discussions were wide-ranging and comprehensive, and reflected the diverse traditions in which we had trained.

We were not all of one persuasion or mind. What united us was a commitment to listen to one another.

Whatever deep insights we might have had as individuals, and however discordant those insights might have been relative to those of another, we did not silence anyone around us.

In the process of interrogating the dehumanising effects of race and the pervasive toxin of racism, we worked to retain our own essential humanness.

What did we learn and what do we now wish to share about the benefits of those many years of dialogue?

We argued, as humans do and have done for tens of thousands of years.

We first examined one of the most persistent and pernicious aspects of race, namely, that it is perceived to be a biological fundamental.

We examined decades of evidence attesting that race does not exist in our bodies.

Skin colour, the primary discriminator of humans, has been shown to be related only to the intensity of sunlight.

The more intense the sun, the more pigment and the darker the skin.

Light skin is literally depigmented skin, an evolutionary adaptation to less intense and more seasonal sunshine.

In the course of the evolution and movement of people over the world, the same skin colours have evolved multiple times.

This is what the early race-makers did not know, but it was upon this faulty scaffolding that the science, philosophy and practice of race was constructed, and from which the process of learning race began.

The idea of race served its purpose well. It divided humanity into distinct types of peoples based on their locations and colours and, eventually, according to a motley collection of physical traits and supposedly distinctive intellectual and cultural attributes.

Soon, hierarchies of races were established. These crudely served the projects of slavery and then, in the modern era, apartheid in South Africa.

Race, it is important to make clear, is an effect of racism. Race and racism do not work in the same ways in different parts of the world.

Race means one thing in South Africa and another in Australia. People classify one another differently in different places and at different times.

Historical contexts are, therefore, essential to examine.

Race, as a human production, works differently according to where it is marshalled. It is the very adaptability and slipperiness of race that has given it much of its power.

These are, we emphasise, not new ideas. And they are hard to digest and to work with practically in one’s life.

Even after acknowledging that race is a social construction, people continue to use the category in uncritical kinds of ways.

Why? Because race is associated with power and, particularly for many who have benefited from it, is desirable.

Understanding the ways in which race seduces us today, both in defence of it and sometimes in ways it is attacked, provides clues for its defeat in future.

Being human is to recognise the overpowering similarities between humans that so outweigh the differences as to render them impotent.

Read: What we can learn from apartheid

This is how race’s canvas will be destroyed.

But it demands that we confront shared concerns, issues that are not able to be allocated to one group and not another.

The relationship between intellectual work and its application in the resolution of pressing social issues is not straightforward.

Where race and racism are concerned, and particularly in societies facing the necessity for profound social change, the political and moral issues at stake often coincide.

Such coincidence prompts an imperative to distil from the research whatever has implications for significant policymaking and systemic transformation.

For these reasons, we believe that the outcomes of our deliberations should attract both local and global interest.

In the deeply racialised society of South Africa, transitioning from ingrained habits of social classification towards porous forms of community, public identity is slowly evolving and needs to continue to evolve in the quest for nonracial forms of social cohesion.

Public education, from early childhood through to tertiary education, has the potential to play a significant role in shaping conditions for shared and necessary social knowledge to undergird new, more democratic, nonracial and non-ethnic expressions of cohesion.

The Constitution is a solemn public covenant that was designed to enable accountable transformative changes to the country’s entire public system.

The fulcrums of transformation are the three tiers of government.

Each represents a site of accountability. Breathing life into, and cutting across them, is the constitutional democracy’s public education system.

National education is designed to support the most serious of national commitments and undertakings.

These undertakings pertain to replacing histories of racialised thinking and living with new forms of community.

The transformation of school cultures in both public and private schooling in South Africa is central to this task.

This includes visioning curriculums that are foregrounded in literacy in a required minimum of South African official languages and that promote the cultivation of empathic teaching and learning.

The ossified pedagogies and teachers of some “good schools” must be recognised as obstacles to societal renewal.

We recognised in our discussions that many social experiments to create an alternative community are transitory movements which come and go.

Even though their potential might be recognised and even welcomed, they seldom achieve grounding and traction and soon die out.

The resilient legacy of existing public systems proves too powerful to change, having become deeply resistant to absorbing, let alone supporting, new forms of thinking and living that have the potential to supplant them.

The urgency of this task is a call to national renewal.

This renewal requires a universal understanding and general comfort with the reality that the predominant “look” of the population will be defined by those living in their millions in the country’s townships, who bore the historical brunt of cross-cutting European conquest and occupation of South Africa.

Both the widespread miseries and presumed benefits of historical race will, thus, be replaced by democratic human effort, individual or cooperative, finding expression under the freedoms and equalities guaranteed by the Constitution.

The legacy of race as historically constitutive of culture would no longer define social, political, economic and cultural reality.

Individual merit will replace choices shaped by entrenched biases and people will not be classified into stereotypes that harden into prejudices.

It needs to be re-emphasised that notions of race, as developed and practised in the recent centuries of world history, were social inventions that could be replaced by different and better ways of moderating relationships between people.

There are grounds for a non-sentimental optimism that the vast majority of people in the country are actively in search of new ways of being human – a new human order – in the country and in the world.

This project, a part of that energy, is a contribution to that historic endeavour.

Ndebele, Soudien, Maré and Jablonski worked with members of the Effects of Race project

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners