The recent violence between South Africa and foreign nationals, following the alleged killing of a South African taxi driver in Pretoria by a Nigerian drug dealer, is an indictment of the entire African continent.

As Africans, we should hang our heads in shame.

When the founding fathers of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) – Kwame Nkrumah, Haile Selassie, Jomo Kenyatta and others – established the organisation in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on May 25 1963, they dreamt of a united Africa characterised by economic and political integration, as well as social cohesion.

The OAU came to the fore after the brutal encounter with colonialism, which not only subjugated Africans politically, economically and socially, but also served to divide and rule by stressing and politicising ethnicity.

The stereotypical politicising of ethnicity took root and has since been enhanced and dangerously entrenched among Africans.

When xenophobic violence flared up in South Africa in 2008, surely the dream of the founders of the OAU was at its lowest point.

There were earlier examples. In fact, the likes of Nkrumah and Selassie must have been highly disappointed when xenophobia raised its ugly head in Ghana in 1969.

There was a terrible setback to their Pan-African agenda when thousands of undocumented immigrants, mainly Nigerians, were forcefully chased out of Ghana after the government of Kofi Busia enacted the Aliens Compliance Order of November 18 1969.

The expulsion of Nigerians from Ghana was certainly unpalatable to the Nigerian government.

When the economy of Nigeria hit rock bottom following the oil crash in 1982, foreigners became a scapegoat.

The government under President Shehu Shagari issued an order on January 17 1983, decreeing that all immigrants who did not have proper papers had to leave Nigeria or face imprisonment.

The “Ghana Must Go” revolution, as the slogan went in Nigeria, affected over 2 million West African immigrants, about a million of them from Ghana.

They were expected to pack their bags and leave Nigeria in the space of two weeks, in time for the January 31 deadline.

As if that were not enough, a further 700 000 or so foreigners were expelled from Nigeria in 1985, including some of those who had proper documentation.

This put further pressure on Ghana, whose economy was not doing well at the time.

A distressing aspect was that families were torn apart, as some Ghanaians were married to Nigerians.

The social and mental scars remain to this day.

This demonstrates that all is not well with the OAU founders’ dream of social integration and cohesion on the African continent.

In addition, there are differences between various ethnic groups in African countries, resulting, in some instances, in ethnic cleansing, as the terrible case of Rwanda in 1994, when perhaps a million Tutsis were killed, illustrates.

Another case in point is that of Zimbabwe in the 1980s, when the government of President Robert Mugabe unleashed extreme violence against Ndebele civilians suspected of being terrorists.

Gukurahundi, as the massacre came to be known, maimed and killed thousands of Ndebeles.

These incidents demonstrate that African societies have too often lost their moral compass.

These disastrous episodes require us to remember that, as Africans, there are many ties that bind us, way beyond the seeds of division sown by some among us.

In particular our history, culture and heritage bind us as Africans, as migration studies demonstrate.

We should draw from this, enabling us to see that Africans are connected to each other by profound links of culture, philosophy and shared historical experience.

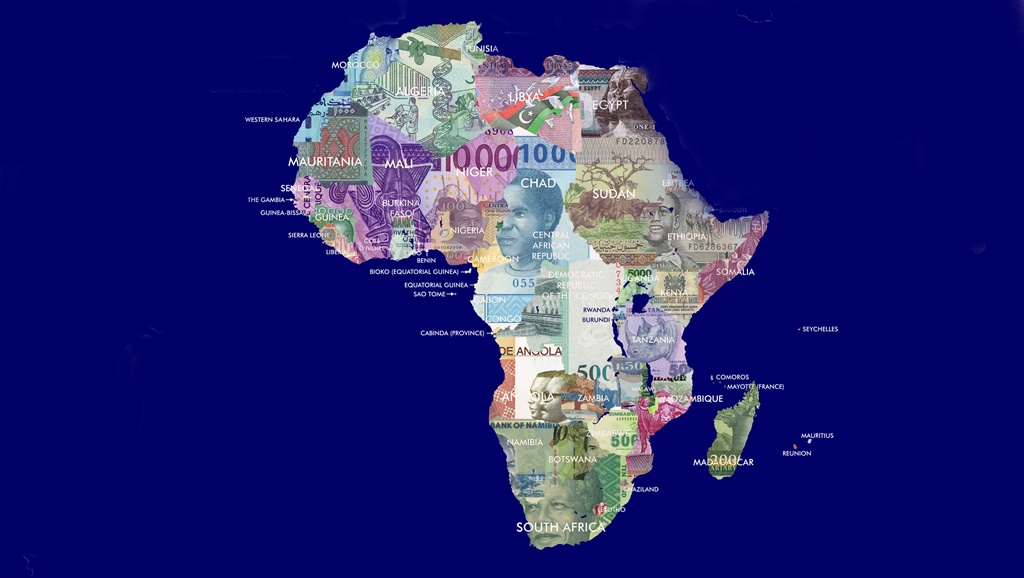

Before the partitioning of Africa by European colonisers, formalised during the Berlin Conference of 1884 to 1885, Africa was borderless.

Though there were conflicts between chiefs and kings, Africans moved seamlessly.

Historians agree that the Bantu-speaking people hailed from near the contemporary boundary of Nigeria and Cameroon.

Over a period of time, they migrated to central, east and southern Africa where they settled.

Ndebeles from Zimbabwe originated from the present day KwaZulu-Natal.

Their leader, chief Mzilikazi kaMashobane, broke away from the Zulu nation in 1882 in defiance of King Shaka.

Mzilikazi and his followers crossed the Zambezi River and settled in the south of Zimbabwe in what later became Bulawayo.

Shaka’s generals, who also defied him, include Soshangane who eventually settled in Mozambique in the Gaza province.

Zwangendaba kaZigudu, the king of the Ngoni in about 1815 to 1848 also hailed from KwaZulu-Natal.

He settled in Mapupo in the western part of Tanzania.

Today, the descendants of the people of this kingdom are scattered in different parts of Tanzania, Malawi and Zambia.

The concept of ubuntu, botho, or ubinadamu in Kiswahili, has always been central in our value system as Africans.

It is through ubuntu that we demonstrate the spirit of humanity, giving, accommodating, sharing, loving and caring.

This spirit has kept us going from time immemorial: without it, xenophobia can easily mushroom.

Reverence for the ancestors is widely practised across many communities on our continent.

This is well captured in Professor John Mbiti’s groundbreaking book, African Religions and Philosophy, which demonstrates that, as Africans, we have long had our own belief systems.

We pride ourselves on this and in no way does this deep feeling of reverence and connection with the ancestors, as we are made to believe, make us children of a lesser god.

Our languages as Africans are interlinked.

For example, the language of the Lozi from the Western Province in Zambia is greatly influenced by Setswana.

This is because the Lozi were conquered by the Makololo army from present day North West in South Africa, led by Sebetwane, in about 1830.

Similarly, we have drawn from the Khoi. For instance, the Xhosa word ‘igqirha’ (spiritual healer) has been borrowed from the Khoi word ‘qira’ and has the same connotation as in Xhosa.

The decision by the South African government to include Kiswahili in schools from 2020 will not only decolonise the curriculum, but go far in educating citizens about the continent.

This heritage month, we should celebrate our cultural diversity as Africans, aspects of which are reflected in this article.

Doing so will bring about much-needed social integration and cohesion, the ingredients of a nonracial society and, above all, firmly place the scourge of xenophobia and tribalism in the dustbin of history.

- Mancotywa is the chief executive of the National Heritage Council

How can we rekindle the spirit of ubuntu in South Africa, especially in our culturally diverse cities?

SMS us on 35697 using the keyword UBUNTU and tell us what you think. Please include your name and province. SMSes cost R1.50. By participating, you agree to receive occasional marketing material

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners