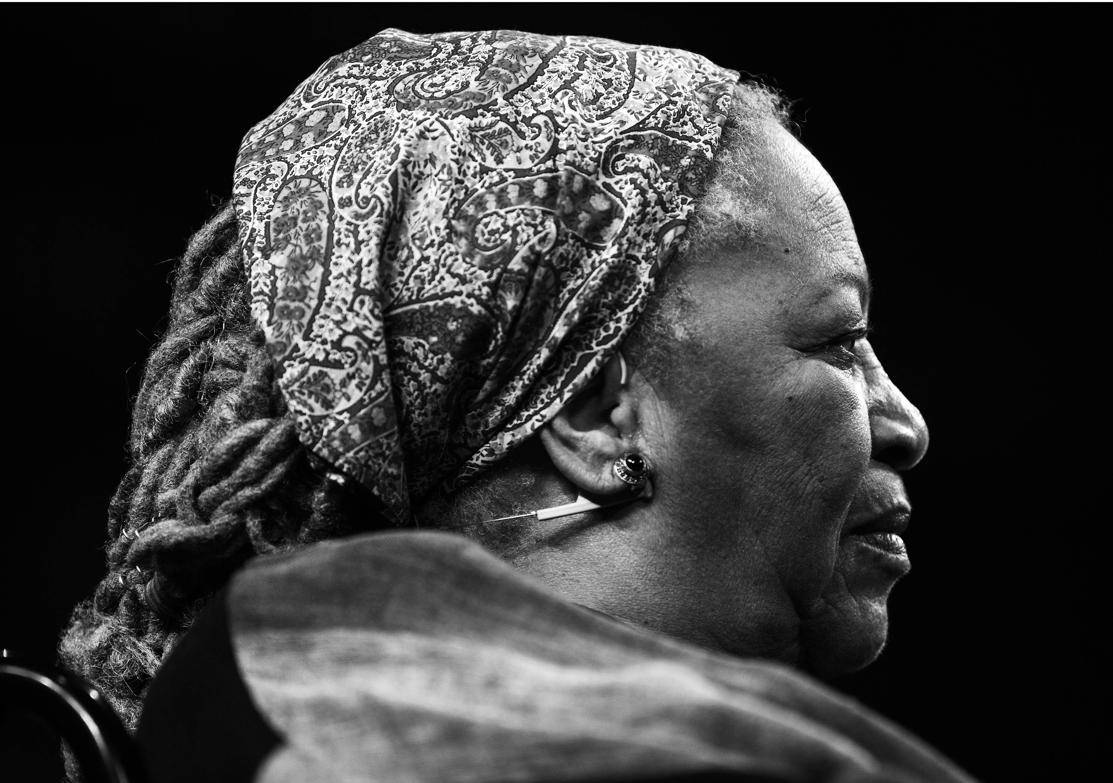

In a moving tribute to Toni Morrison, the American writer who touched the heart of black life across the planet, Manosa Nthunya can’t help but accept that the greater struggle is still very much alive

There’s a rather troubling similarity between the death of Toni Morrison and that of Nelson Mandela. They both, it seems to me, died as quite unhappy people. When Mandela passed away in 2013, the Slovenian philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, observed that Mandela must have died a bitter man as the acclaim he had received from all corners of the world, including from socialists and corporate business, was an indication that his life and political sacrifices had in fact done little to change the social and economic status of the people he had sacrificed his life for.

Žižek wrote: “We can safely surmise that, on account of his doubtless moral and political greatness, he was at the end of his life also a bitter old man, well aware how his very political triumph and his elevation into a universal hero was the mask of a bitter defeat.”

It is this defeat that has become glaringly obvious in present-day South Africa, where daring to mention Mandela’s name, particularly in the affirmative, one runs the risk of being seen as morally compromised; of not understanding that the economic crisis that the country currently finds itself in was in fact, in part, a consequence of Mandela’s making when he chose, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, to engage in “closed negotiations” with those who are today threatening to leave the country and consequently destroy its economic system.

On the other hand, in praising Mandela, Morrison said: “Nelson Mandela is, for me, the single statesman in the world. The single statesman, in that literal sense, who is not solving all his problems with guns. It’s truly unbelievable.”

The rude irony, of course, is that Morrison passed away two days after a white nationalist used a gun to kill 22 people in a racist act meant to communicate his despair over the changing racial demographics of the US, which he seemingly could not accept. The tragedy that belies his actions is that the very same “white” America he today wants to preserve has in fact claimed “America” as home because of a genocide that was unleashed on Native Americans, from the 15th century, and the continued discrimination they are subjected to as they are marginalised in America’s political, social and economic activities.

In interviews that Morrison gave after the election of Donald Trump as US president, she described him as “so ignorant, so vile, so shallow, so self-centred, egocentric, vengeful” and “corrupt without embarrassment”. It was, indeed, difficult for Morrison to understand how a racist president could have been elected to the highest office in the “free world” right after it had put its first black president in power. Interestingly, though, when Barack Obama was elected president, Morrison said, on numerous occasions, that she found it curious that this had happened when she was aware of how there were murmurs from the far right calling for a return to America’s so-called golden age. This was a period after World War 2 when America experienced an explosive economic boom. It was, however, a boom that, predictably, did not drastically change the political and economic situation of African-Americans.

I can therefore surmise that, similar to Mandela, who dedicated his life in service of black South Africans, Morrison, who dedicated her life to literature, and “who in novels characterised by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality”, as her Nobel prize in literature citation read, must also have died unhappy, as she was well aware that the enormous dignity that characterised her representation of African-Americans in her literature was under threat in her final years.

And here lies a bitter historical lesson for those of us in South Africa. Fighting against an oppressive system is no guarantee that the system will ultimately be defeated. It may as well be the case that the iconic status that Morrison and Mandela enjoyed at the times of their deaths was just an honour to their attempts to change circumstances that they could not ultimately, individually or even collectively, achieve. Evidence from both their countries suggests that the poor, and women, continue to be despised even as we are increasingly being told that we have entered the fourth industrial revolution.

The praise that Morrison received when she was alive and after her death is testament to the fact that during the time that she was with us she told her truth in the best way she knew, and that was through her searing art. She has been an extraordinary and a peerless interlocutor and has greatly sharpened how many of us think.

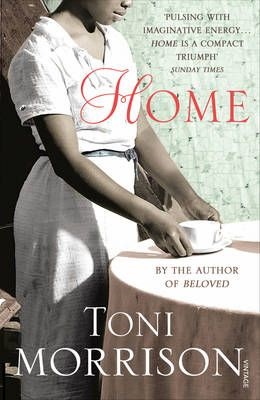

While Morrison’s most popular novels are Beloved, The Bluest Eye, Sula and Song of Solomon, my personal favourite is Home, published in 2012. This slim novella follows the life of Frank and Cee Money, and interrogates themes of home and belonging in America in the 1950s. In many ways, when read in 2019 in the context of a fallen empire, the novel’s important questions about history, home and the future are questions undoubtedly haunting black Americans today.

In South Africa, on the other hand, many young people have started to ask deep questions about the country’s democracy as most of them feel, despite attempts to convince them otherwise, that they have in fact benefited very little from South Africa’s democracy. Indeed, even the benefit of being able to express their views is one that is met with mockery. It is unclear to many of them if the “freedom of expression” or “crumbling economy” that they are consistently told about can adequately respond to a stomach that “groans a friendly smile to hunger”, as aptly depicted by South Africa’s poet laureate, Mongane Wally Serote, in his poem City Johannesburg.

If these are the questions that many South Africans are today posing and as they seem, to many, to increasingly threaten the “stability” of the country, it should always be borne in mind that the victims of social upheavals and of economic inequalities are always mostly women and, in our context, black women.

A large part of Morrison’s intellectual life was devoted to showing the suffering that black women in America have experienced under different tragic historical circumstances. In her acclaimed novel Beloved, she chronicles the consequences of slavery on her protagonist, Sethe, who decided to slit her infant’s throat to prevent her child from becoming a slave. The repercussions of this act are lethal. The infant, Beloved, returns as a ghost to haunt the family, to refuse them any peace. What Morrison communicates here, which South Africa would do well to learn, is that attempts to hide or bury history never work because history, like a ghost, always returns to haunt whatever stability a nation may want to have.

Morrison’s novels have probably received the most praise for showing the tremendous strength of her African-American woman characters. Despite the great challenges they face, they rise to the occasion as they are always almost able to form supportive communities that allow them to survive. If, then, in expounding on Žižek’s sentiments on Mandela’s death, I suggest that Morrison must also have died bitter, I would like to warn that, in remembering Morrison’s legacy in South Africa, and as we importantly celebrate Women’s Month, our political leaders and all of civil society would do well to always remember that the vast majority of victims of social upheavals and drastic inequalities are black women, despite the remarkable resilience they continuously show while dealing with monumental challenges.

We therefore owe it to our history, and our future, to ensure that we do not make their continued suffering come to seem like a historical inevitability.

- Nthunya studies the work of Morrison and Zoë Wicomb as a PhD candidate in literature at Wits University. He studied literature, history and philosophy at Rhodes University

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners