Schools retain discourse and hegemony of Christian nationalism, writes Nuraan Davids

Despite reform measures, South Africa’s public schools continue to promote a Christian ethos at the expense of other religions or faiths.

This is evident in many ways, some quite overt, others less so.

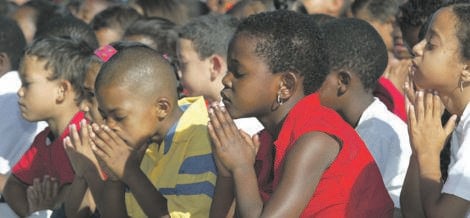

Consider, for example, how a number of schools conduct their assemblies preceded by a hymn and a prayer, or the choice of the invited speaker, who is often from the local church.

In some instances, “out of regard”, learners from different faiths, or those who do not prescribe to any, are allowed to excuse themselves from these assemblies.

Consider also the choice of music sung by the school choir, or the annual school play, most commonly known as the Nativity play.

Similarly, in classrooms, when teachers invoke the wrath or displeasure of God in order to discipline learners.

There are three major concerns with what is being described here.

The first centres on just how prevalent the disregard for diverse religions, cultures, traditions or philosophies at schools is.

The second is on the capability and, more importantly, willingness of teachers to step out of their own religious identities and not only consider those of others, but recognise values and world views that connect learners, rather than those that separate them.

And the third focuses on the implications for democratic citizenship education.

Read: Religion must self-regulate

Our department of education’s 2003 National Policy on Religion and Education is premised on the promotion of religious diversity, “moral regeneration, and the promotion of values in our schools”, by exposing learners to the diversity of religious traditions that constitute our nation.

The replacement of religious instruction with religion education (RE) sees a shift from a monomorphic narrative to a diverse and inclusive policy that is intent on promoting mutual recognition between citizens, regardless of their religion, culture or ethnicity.

To achieve this initiative, the policy posits that the relationship between religion and education “must flow directly from the constitutional values of citizenship, human rights, equality and freedom from discrimination, and freedom of conscience, religion, thought, belief and opinion”.

However, as welcoming as this policy might be to those who understand the necessity of acknowledging and promoting pluralist identities and values, the policy demands a “religion literacy”, which might not be as welcomed by teachers, principals and parents.

While research raises concerns about teachers’ poor subject knowledge of different religions, even when teachers have insights into a multireligious approach to teaching RE, they could not recognise that teaching and encouraging Christian prayer, for example, is also a form of proselytisation – which revealed the deep-seated Christian framework still operating in post-apartheid culture.

Read: Photography: Youth, religion & South Africa

Consequently, there have been numerous cases involving the state and parents, in which attempts have been made to either insist on the retention of Christian-based schools, or compel schools to adhere to the current policy on RE – that is, that one religion cannot be given preference and that schools are essentially religious-free zones.

From the outset, therefore, the policy has provoked resistance among not only teachers and principals, but parents and religious bodies.

Central to the criticism from parents is that, although the state purports to separate religion from the state, its action to propagate religious diversity is interpreted as an interference in religion, rather than a neutral separation.

Central to the state’s position is that we need religious literacy for the recognition of different world-views and cultural practices, as well as the capacity for mutual recognition, respect for diversity, reduced prejudice and increased civil toleration, which is necessary for citizens to live together in a democratic society.

Despite desegregated school spaces, the lived experiences of most learners are neither connected nor integrated with the prevailing ethos of a school.

Not only do learners struggle to find points of resonance in race and language, but they fail to encounter any evidence of a diversity of religions, cultures and traditions.

When schools disregard this policy, they are retaining an apartheid-based discourse and hegemony of Christian nationalism.

There are two clear messages here. To learners who share a Christian world-view, the message is that your beliefs are the only ones that matter, and that you do not have to learn about the beliefs or views of your classmates.

The message to learners who do not share this world-view is that who they are and what they believe and practice will not be afforded any recognition.

For both sets of learners, their socialisation into citizenship in a pluralist and democratic society is fundamentally compromised and antagonised.

There are direct links between what children learn and encounter at school and the kinds of citizens they eventually become.

The less children engage with difference and diversity, the narrower their world-views, and their capacity to cross over into different perspectives.

We see how incidents and rhetoric of intolerance and incivility continue to hamper and undermine notions of peaceful co-existence and respect in our democracy.

Schools should not have the right to neglect their constitutional responsibility in developing and cultivating learners who are mindful and able to function in diverse, pluralist societies.

When schools and parents resist learning about others, they fail to learn about themselves and they fail to see their shared humanity with others.

Schools must be accountable to their function of serving a public good.

This means nurturing learners who take pride in pluralist ways of being, who are mindful of discrimination and exclusion, and who see themselves as both participants in and contributors to South Africa’s democracy and the advancement of peaceful co-existence.

Davids is professor and chair of the department of education policy studies at Stellenbosch University. Her research interests include democratic citizenship education, Islamic education and gender issues

TALK TO US

Do you share the concern about Christian hegemony being imposed on learners in the schooling system?

SMS us on 35697 using the keyword PLURALISM and tell us what you think. Please include your name and province. SMSes cost R1.50. By participating, you agree to receive occasional marketing material

|

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners