Françoise Malby-Anthony, a chic Parisienne, fell in love with South African conservationist Lawrence Anthony and together they founded a game reserve. But after Lawrence’s death, Françoise faced the daunting task of running Thula Thula without him. In this extract from her book An Elephant in my Kitchen, she recounts the harrowing experience of poachers attacking their rhinos.

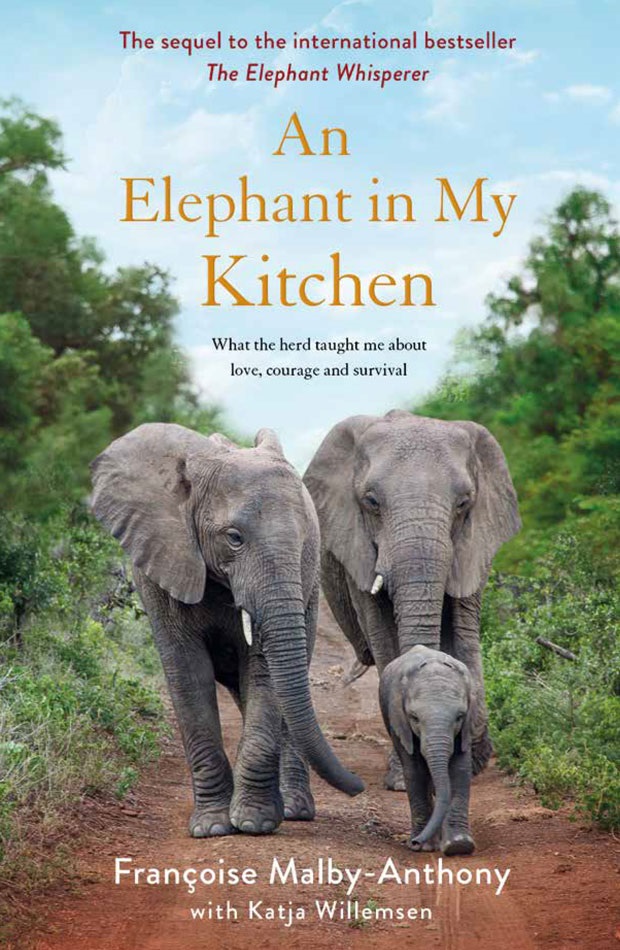

An Elephant in my Kitchen by Françoise Malby-Anthony and Katja Willemsen

Publisher: Pan Macmillan South Africa

I stood in front of the kitchen fan, twisted my hair out of my neck and tried to focus on what my chef Winnie was saying.

It was the third sweltering day of 40-degree temperatures and I was dead on my feet.

We all were.

The news of Lawrence’s death hadn’t yet sunk in but there was no time to stop. The lodge was full and we were doing our damnedest to soldier on.

‘I think mango and avocado salad would be a good starter in this heat,’ Winnie suggested in her gentle way.

I nodded vaguely. Lawrence had loved mangoes.

I looked up towards the noise coming from the office. Someone was broadcasting the same message over and over on the two-way radio.

‘Elephant Safari Lodge, do you copy?’

Silence.

‘Vusi? Mabona? Do you copy? Nikuphi nina?!’

I couldn’t make out who the ranger was but he sounded panicked.

I was about to answer when my mobile rang.

‘Is that you on the radio, Promise?’ I asked.

‘Françoise, poachers. Thabo took a bullet.’

I gripped the phone. Thabo, our rhino calf. ‘And Ntombi?’

‘She’s fine but won’t let us near him. We can’t tell how badly he’s hurt. We need Mike here yesterday.’

I sat down, fighting off a wave of nausea. The two weeks since Lawrence died had been a blind scramble of decisions and new situations but nothing was as scary as this.

‘You still there, Françoise?’

‘Just trying to figure out how to get hold of Mike,’ I said.

We always used Dr Mike Toft for animal emergencies, but he was three hours away by car, or thirty minutes and 30,000 rands by helicopter.

I hoped to God that he wasn’t tied up in another crisis.

‘Does Alyson know what’s happened?’ I asked.

‘She’s on her way.’

‘Good. If anyone can get close to Thabo, it’s her. Stay with them and call me if anything changes. Leave Mike to me.’

Alyson was our rhino calves’ stand-in mum and primary carer and they trusted her completely, but that didn’t mean they would let her check his wounds.

Besides, injured wild animals are unpredictable and dangerous.

Lawrence had always handled animal emergencies and I had no clue what to do.

I glanced at my phone. Still no call from Mike. In a couple of hours it would be dark and too late to attempt treatment.

I was shocked that the poachers had the gall to breach our electric fence in broad daylight.

They hadn’t even bothered to use silencers.

Ever since Thabo and Ntombi were old enough to leave the safety of the orphanage to be free rhinos in the reserve, they had been protected by armed guards. Perhaps the poachers knew that Lawrence had just died and assumed that security had dropped?

I felt helpless and out of my depth. I radioed Promise for an update on Thabo.

‘He’s just standing there, not moving. Spooked and in shock. There’s a lot of blood but Ntombi still won’t let us close, not even with Alyson here. The damn hyenas have already smelled blood and are pestering him.’

I sank back into my chair in despair. Thabo and Ntombi had been doing so well on their own. About a year ago, Alyson and the rangers had started the long process of familiarizing them with the bush. They took them out on daytime walks to teach them where the watering holes were and to help them discover bush smells, vegetation and animals that they would encounter.

Every night they were brought back to the safety of the boma, until one evening they didn’t want to return.

Nerve-wracking for us, but we knew it was a healthy sign and time to let them roam free.

I began to pace the room. How would I pay the vet fees? What if Thabo died? First Lawrence, now Thabo.

I’m usually good in a crisis, but I couldn’t get my thoughts straight and still couldn’t get my head around the fact that armed men had come into the reserve to kill Thabo and Ntombi.

I only realized much later how naive that was. You can’t patrol forty-five kilometres of fencing every minute of the day and night.

When Lawrence was alive, security took up a huge chunk of his time.

He had been closely involved with patrols, snare and fence monitoring, and dealing with all the poaching incidents.

My poodle Gypsy panted in the heat at my feet. I felt her big black eyes on me and stroked her absent-mindedly, checking my phone.

Still nothing from Mike. I picked Gypsy up and held her against me, burying my face in her fur and fighting back tears.

She snuggled deeper into my neck. I felt her warm breath on my skin and wished I could stay in her sweet embrace forever.

But I couldn’t. I had an animal in trouble and I couldn’t sit back and do nothing.

‘Let’s get to work,’ I whispered and carried her with me to the office.

She sat on the chair at the other side of my desk and kept a watchful eye on me while I focussed on bolstering security in case the poachers returned.

I couldn’t run the risk of pulling our existing guards away from their patrol areas, so I phoned the security company Lawrence used for emergencies and they promised to dispatch two extra armed men in the morning.

We weren’t off the hook by a long shot because I had only enough money for them to stay for one month, but it was a start.

I would protect Thabo and Ntombi even if it bankrupted me. They would not be killed on my watch.

Mike Toft called at last with the bad news that he was in the middle of another poaching crisis and wouldn’t get to us that day. I told him the rangers had seen Thabo take a few steps.

‘That’s good news. If he’s walking and not in obvious pain then the bullet probably didn’t damage any bones,’ he said.

‘He won’t be comfortable but it doesn’t sound life-threatening. I’ll be there first thing in the morning. Keep him safe until then.’

The poachers hadn’t managed to get the horns they had come for and I was terrified they would return. No one slept a wink that night. Thabo and Ntombi were skittish and didn’t want the rangers close to them, so the men tried hard to give them space while still keeping them safely within eyeshot.

Thabo eventually lay down but Ntombi stayed vigilant and spent most of her time chasing off hyenas.

Rhinos have terrible eyesight but a superb sense of smell, so Ntombi knew these small but dangerous predators were around and became so distraught, snorting and stress-shrieking, that the rangers stepped in and helped her chase them off.

By 6 a.m., two ex-military men arrived to reinforce our security. They walked bolt upright and their restless eyes constantly scanned their surroundings. What a relief. An hour later, Dr Mike Toft arrived. He immediately darted Thabo while Alyson and the rangers kept Ntombi at a safe distance.

‘It’s a flesh wound,’ he announced.

Alyson radioed the news to me. ‘The bullet missed the bone by millimetres.’

I will always be grateful that those poachers were such useless marksmen.

Good came out of this terrible attack, because it spurred me on to launch our own rhino fund.

I realized that without money, my animals weren’t safe and that having our own fundraising organization was the only way I could be sure always to have emergency cash on hand.

Money flowed in, enough to pay the extra guards for more than a month and to buy extra weapons and security equipment.

I hate guns, but poaching is a war and the only way to fight it is by being prepared for the worst – and that means being armed.

I will never forget those frightening twenty-four hours after Thabo was shot, but they helped me to define the purpose of my life without Lawrence and I understood with such clarity that the mantle of protecting Thula Thula’s wildlife had become mine, and mine alone.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners