South Africa has a healthcare dichotomy, and the inability to reconcile the needs of both public and private interests has led to a deepening crisis of inequality.

On the one hand, you have a largely dysfunctional state-run system, characterised by crumbling infrastructure, poor delivery and a seeming inability to come to terms with the needs of the majority of the country’s citizens. This is not to say it does not have some level of success, but to suggest it is adequate or efficient is disingenuous and dangerous.

To be sure, the government allocated R222.6 billion for the provision of health services for the country’s 57.7 million citizens this year.

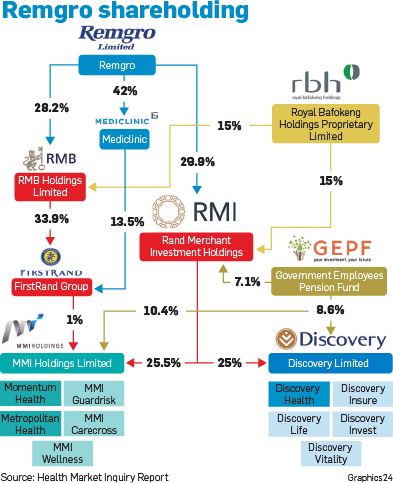

On the other hand, you have a densely concentrated private health system, marked by outpriced medical aids and hospitals locked in a symbiotic dance of payment and delivery, drawing skilled doctors into its vortex of networks which are available, essentially, only to an estimated 9 million citizens who have the income to participate.

This is unsustainable.

The much-vaunted National Health Insurance (NHI) is beginning to gather pace in implementation, yet faces very real challenges which, if not addressed, will scupper what is arguably one of the country’s most ambitious and crucial interventions since the implementation of the social grant system. It’s failure will lead to a critical failure of the country’s national health service.

As with any other critical services the country requires, and one that is enshrined in our Constitution as a human rights imperative – education, electricity, water, housing and health – the engagement of the private sector carries with it a fraught morality.

How does government engage with a entity that is, at its core, driven by the need to maximise the return on its capital investment to the benefit of private/institutional shareholders, while at the same time ensure that the NHI – which is poised to become the biggest procurer of health services – is fairly priced, efficient and sufficiently effective to serve the country’s health needs?

To get to grips with the modalities of the private health system, the Competition Commission released the final Health Market Inquiry report this week after a five-year investigation into competition in the sector.

The conclusions were neither kind nor sparing. They paint a damning picture which, if not specifically named as collusion, can certainly indicate a market of self-serving interests, where private hospitals, medical aids and doctors exist.

At the coalface sits the citizen, the person in medical need, who is neither considered nor catered for beyond the provision of a service that they have no power in negotiating and can measure neither the outcome of nor the quality of the care received. They are unable to do this as there is no mechanism within either private or public health that gathers this data.

Additionally, medical funders or medical aids have been allowed to operate in a regulation-free environment which has distorted competition. No clear offers of service, too many medical aid options and exclusionary practices which put the health of many who cannot afford it at risk.

The consumer is at the whim of the providers’ discretion and, in fact, is a victim of a “perverse incentive” where fee-for-service drives hospitalisation which in turn has unnecessary cost implications.

The deconstruction of this symbiotic system is necessary to ensure that fair and adequate access to healthcare is available for everyone.

The Competition Commission’s recommendations in this regard are wide-ranging and deep, and it warns that market failures will persist if a partial intervention only is applied.

Among its recommendations are both the regulation of the supply side and the regulation of the demand side of health. Several regulatory bodies are suggested to manage the outcomes of both and ensure competitive pricing and accessibility.

To combat the high concentration of hospital care by the three players – Netcare, Mediclinic and Life Healthcare – the commission will review their approach to creeping mergers. It also recommends the establishment of a dedicated healthcare regulatory authority (SSRH) to regulate the suppliers of healthcare services which includes health facilities and services. The SSRH will have four main functions: healthcare facility planning (where hospitals are situated and licensed); economic value assessments, monitoring health services and health services pricing.

Crucial to future pricing will be a multilateral negotiating forum for all practitioners to set a maximum price for prescribed minimum benefits. Where no agreement is reached, an arbitration process will come into play.

For practitioners, there are interventions to promote competitive pricing and a move away from fee-for-service contracts.

Funders or medical aids are encouraged to offer a single, standardised base option to increase competition. This will offer consumers a chance to compare prices and reward those that are innovative and are able to offer lower prices. In addition, the introduction of a risk adjustment measure to medical aids will remove the incentive of medical aids to compete on risk. Schemes should compete on metrics and not age,health or risk profile.

While the Competition Commission’s final report is an elegant document, which rationally describes the flaws of the sector and the recommendations to bring it back into line, at the centre of this lies the role of the government.

Its failure to implement a rigorous regulatory regime can be blamed largely for the rampant rise of the private health sector and the vacuum in which it operates. Its control over the public health sector has been poor.

For its part, the government lacks capacity for effective administration, it is unable to retain doctor skills and appears to turn a blind eye to ailing infrastructure or to building new hospitals.

It cannot rely on the private sector to save it.

What it can and must do, is to use its looming procurement influence to negotiate pricing in its favour. It must, as an imperative, force the participation of the private sector, without consideration for shareholder interest beyond a certain threshold.

It must, too, get its own house in order. To add a bad apple to a healthy basket will spread the rot everywhere.

Ultimately, if there is no consensus between these opposing factions, our health system is doomed to collapse.

|

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners