Tafadzwa Z Taruvinga’s memoir is about his experiences of poverty, xenophobia, racism and classism as he attempts to create a different life for himself and his family. Manosa Nthunya dives into this searing memoir.

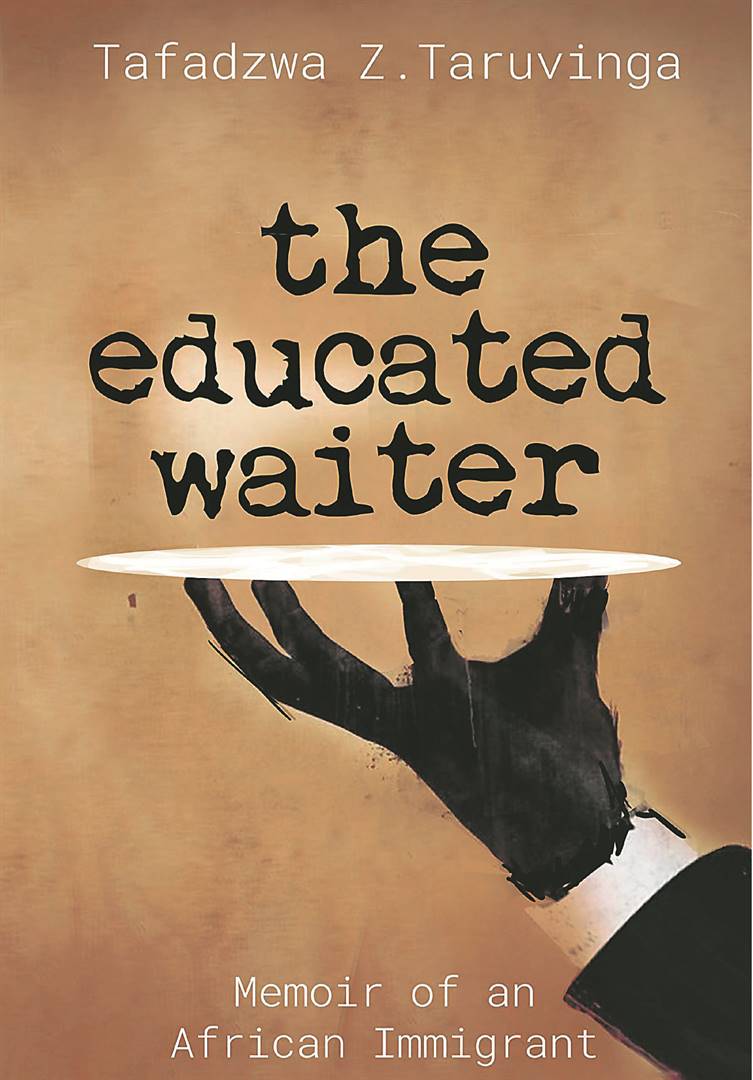

The Educated Waiter: Memoir of an African Immigrant by Tafadzwa Z Taruvinga

Published by MFBooks

240 pages

R249

When one reads a book, there’s always an unconscious expectation, although naïve, that it will have a beginning, middle and an end.

This is because books are always about something and after we are done reading them, we hope for some form of resolution – be it tragic or hopeful.

We unconsciously demand that things should knit together for the narrative to make sense.

This is however an experience I did not have after reading Tafadzwa Z Taruvinga’s book, The Educated Waiter: Memoir of an African Immigrant.

Troubled by this feeling days after I finished reading it, it became apparent to me why this might have been the case.

The immigrant, and in particular the African immigrant, is by definition someone who is always on the road.

And the question of resolution, for most of them, is one they are precluded from experiencing.

This consequently means that their narratives, by historical necessity, will not be conventional, making the experience of reading similar to the experience of migration – uncomfortable and unpredictable.

Taruvinga’s searing memoir is about his experiences of poverty, xenophobia, racism and classism during his journey to create a different life for himself and his family.

Like most people, he had hopes that attaining a world class education would be his way out of poverty.

And having moved from Zimbabwe to South Africa to study for an economics degree at Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape, his hope was to change the quality of life of those he had left behind and to fulfil his own dreams.

He rudely learns that even the best education has limits.

That is how he becomes a waiter – an educated waiter – as he reckons with the fact that being an African immigrant, even in another African country, comes with boundaries he could not have foreseen.

I ask him what this realisation meant: “I thought my education would be an automatic pass to prosperity and success in the corporate world and all the dreams I had. The irony was that I had this fantastic degree but it didn’t give me immediate access [to work opportunities].”

That access, however, is still unguaranteed because three years after applying for a work permit, he is still waiting for a response.

Taruvinga starts his memoir by recounting his experiences of poverty while studying at Rhodes University in 2002.

In one disturbing incident, he details how he had to eat a mixture of cornflakes and Knorr soup as he had completely run out of food.

“I poured the boiled water into the bowl and carefully added a few granules of Knorr soup powder over the crushed smithereens … I was hungry. For most [people] it would seem unfathomable, eating a meal that wasn’t one. But I wanted to graduate with a Rhodes University degree so badly that ‘Knorr cornflakes’ seemed like a reasonable meal.”

Being unable to afford food and shelter forced Taruvinga to look for a job. He found one, cleaning toilets in a restaurant.

“The idea that I would clean toilets felt depressing,” he writes. “I had left Zimbabwe to find greener pastures. My dream did not include scrubbing brown shit skid marks off a toilet bowl.”

But in order to have a meal, he had no other option.

Eventually he was hired as a waiter, a job he would depend on – to his surprise and the reader’s – for much longer than he thought.

After graduating Taruvinga had hoped that things would get better. He did not anticipate the racism and xenophobia he would encounter in corporate South Africa.

Now based in Johannesburg, he recounts a chilling experience of a colleague who demanded that he should make her coffee despite this not being his responsibility.

“Marieke insists on my making her coffee, first thing when she comes in every morning ... She makes it clear that Patricia the administrative assistant ... shouldn’t make any [coffee] for her. I, the finance assistance, should.”

This is an experience Taruvinga is confronted with in many of the jobs he finds (and has to leave), as he experiences discrimination in how people relate to him and in how much he is remunerated.

It is a vulnerability made possible by his race and by the fact that, as he says disparagingly, he is referred to, like many other African immigrants, as a “foreign national”.

Something that increasingly dominates his life, after struggling to get his degree, is getting a work permit, with great consequences of being unable to accept job offers.

It is however evident to Taruvinga that what is behind his inability to get a work permit is the discrimination that South Africa has against African immigrants as opposed to Europeans.

These are immigrants, he writes, who are called “expats, and are treated with respect and dignity, while African immigrants are referred to as “foreign nationals – and sometimes abased, as though they were rats surrounding a lump of cheap Gouda [cheese] by the dustbin”.

The repercussions of this, he writes, are that many African immigrants have to “wait for years before they are able to obtain all the listed requirements [by the department of home affairs], if they ever do. Many give up, along with the employers who were ready to welcome their new foreign recruits into their diverse teams.

It’s as though the South African labour market is resistant to the skills “from Africa” that it so clearly needs.

“This is a perplexing, and at most times infuriating, paradox,” he writes.

It is however not only in the labour market where such prejudiced encounters are pervasive as they also exist in the social sphere.

Taruvinga retells the horrific story of Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, the Mozambican vendor who made headlines when he was torched to death in 2008 in Alexandra township.

This tragic incident had a huge impact on him as it exposed the precarity that had become a feature of the lives of many foreigners in South Africa.

Nhamuave, he writes, was “burnt in minutes like charcoal, his charred body takes two weeks to identify. Two years later, in 2010, an informal inquiry will be held. No one is charged.”

While Nhamuave’s death brought great disappointment, the political and economic situation in Zimbabwe was getting worse.

The elections in 2008 turned violent and it was reported that there were “six politically motivated rape cases, 107 mysterious deaths, 137 abductions and 1 913 cases of assault” and during this time, Taruvinga writes: “Poverty tightens its grip. Workers commute to work in kombis, but, when they finish a day’s work, many can’t afford to commute back [home]. They have to walk.”

His inability to secure a good job, and an increasing feeling of vulnerability, leads to Taruvinga apply for an internship in Germany.

It is here, he hopes, where his fate might change but as things turn out, that does not happen.

This internship opportunity does not lead to a recruitment and just like in South Africa, he finds racism and xenophobia pervasive in Germany.

This is revealed, in one instance, when he goes clubbing with a new friend he made since arriving in Germany.

The two are refused entry into the club and it is evident that this refusal is based on their race.

When Taruvinga tells the friend that they should leave, the friend refuses.

Mwangi, who works as a caretaker at McDonald’s and has a Master’s degree from the Kenyatta University in Nairobi, tells Taruvinga that he would rather wait tables and suffer such abuses instead of returning to Kenya.

He says to Taruvinga: “Look at where we are sitting now. Right now. The streets of any city in any West European country are fully paved with granite stones.

“But does Germany have a lot of granite in the countryside? Nope. Where does the granite come from? Tell me … Zimbabwe, of course! And from any other African country where there is plentiful [granite] … Why should I not spend an hour negotiating to get into a club in Germany, rather than not being able to afford going to a club at all, back home in Kenya? Why should I settle for an office job there which pays me a quarter of what I earn here cleaning toilets at McDonald’s?”

The Educated Waiter is a memoir with a deep interest in the predicament of African immigrants and their often heart-breaking experiences in the contemporary world.

How did they, in Frantz Fanon’s words, again become “the wretched of the earth”?

Why, Taruvinga asks, is it the case that a continent with so many resources, Africa continues to be so poor?

And what responsibility do young Africans have in changing this precarious condition that has come to define their lives?

This uncompromisingly vulnerable memoir therefore attains its agency in that it denotes a contemporary human experience.

When I ask Taruvinga why he decided to write it, he says: “I got tired of struggling to the extent that I felt it needed to come out. In the last six years this book started speaking to me more vocally than any other. I felt an intense need to document it.”

I tell him that what I found moving is the way he depicts the role his mother has played in his life.

From the time he was young, having lost his father at the age of seven, Taruvinga’s mother, Mhamha, made every effort to take care of him and his siblings.

Even during his experiences of unemployment and becoming an educated waiter, his mother did not flinch in her support.

One of the most moving scenes is when Taruvinga has to return to Zimbabwe as South Africa, and other parts of the world he has travelled to in search of a better life, have failed to change his circumstances.

He decides to partner with his mother in her chicken business.

He helps her in buying and selling the chickens. It is while selling chickens that Taruvinga meets his first real love.

The adventure is brought to an abrupt end as the country’s economic crisis deepens.

Taruvinga finds his way back to South Africa to try his luck again despite his reluctance to do so.

“I want to live and work here [in Zimbabwe]. I don’t want to go back to South Africa, unless I can get a good job there … It’s hard to forget how exhausting the social complexities of the place can be. The racism, the xenophobia, the violence. Besides, I don’t want to live far from home. I want to be able to regularly visit Mhamha,” he writes.

But with Zimbabwe’s economy in free fall, he is forced to return to South Africa and once again work as an educated waiter. It is apparent on this return that Taruvinga has been completely shattered.

He writes: “Keeping myself motivated is a mammoth task. I work. I eat, sometimes. And at other times, I live on stolen leftovers. In the morning I poop and brush my teeth and I shower. And go to work and I eat again and I sleep. That’s all I do. I live a mundane, repetitive existence. I think I’m depressed.”

At the end of our conversation I ask him what he hopes the reader will take from the book.

“Hope. Things have the potential to get bad or uncomfortable and they do so in the lives of a lot of people. And when that happens it’s very easy to stop moving on and pursuing one’s dreams. One needs to keep moving forward.”

And that, in the 21st century, has become the quintessential experience of the African immigrant.

“Moving forward” without even the fantasy of a map to act as a guide.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners