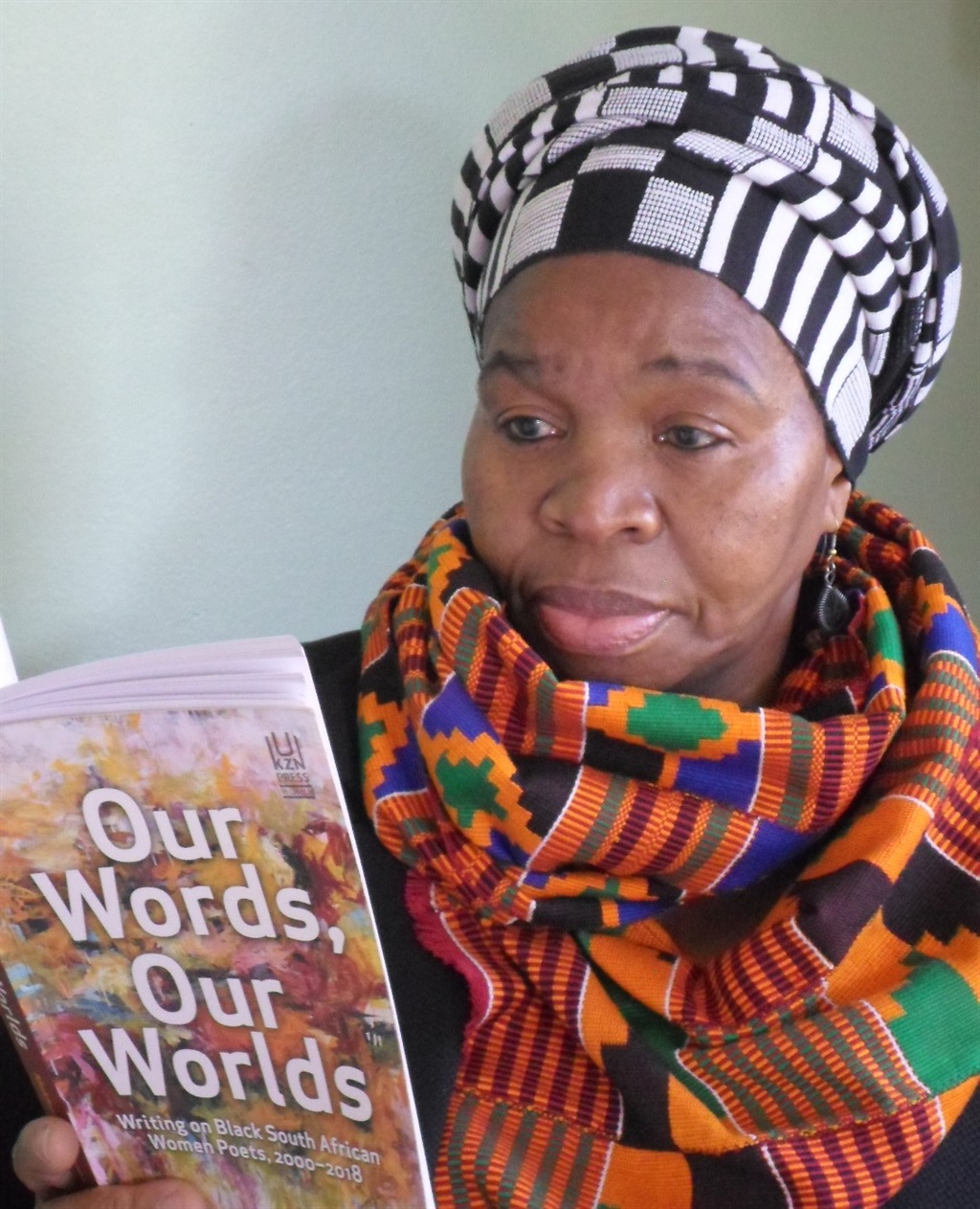

Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000-2018

Edited by Makhosazana Xaba

UKZN Press

328 pages

R315

.....

I was recently given an opportunity to teach literature part time at a university in Johannesburg and, in the poetry section, I chose to teach the poems of Lebo Mashile and Mongane Wally Serote, some of my favourite South African poets. While the noble vocation of teaching is meant to inspire critical thinking and deep reflection, the teacher never knows how the students will respond to what is being taught.

This was my experience while teaching Mashile’s I Smoked a Spliff with Jesus Christ Last Night from her 2005 collection, In a Ribbon of Rhythm. Things turned out to be more controversial than I had anticipated.

The poem is an examination of love and loss and there’s an imagined conversation between the speaker in the poem and Jesus Christ. The speaker tries to make sense of life after an unexpected and painful breakup.

The lines that caused controversy are when the speaker says: “But he was Jesus, and I’m a sister/so I’ve been through more shit/Cuz I’m black, and life is hard in Jozi when you’ve got tits.”

Immediately after reading these lines a male student raised his hand to ask: “Why is Lebo comparing herself to Jesus when she has never died on a cross? Does she know the pain and betrayals that Jesus went through?”

To my surprise, I heard a loud unison “Yesss!” from all corners of the classroom, including from female students. As the class was becoming somewhat rowdy, I noticed that four female students had raised their hands.

After I asked one of them to respond, she said: “But she’s black and Jesus is certainly not black and he is also not female. Can Jesus therefore say he knows Lebo’s experiences? Why, sir, do women continue to suffer if Jesus died for them on the cross?”

Again, to my surprise, the students responded with an even louder “Yesss!”

After these two incidents I could sense that the students were also surprised at what had happened, as the class went quiet after the uproar.

It was evident that perhaps for the first time since leaving home, most of them had never thought about the contradictions that might inhere between their religious beliefs and what seemed to be their awareness of the ways in which women have been marginalised in society.

At that point I knew I had to act responsibly, despite my own views on religion. I made it clear that Mashile’s poem was not anti-Jesus and that it was always possible to be a Christian or be of any religious or cultural persuasion and still believe in the equal rights of the sexes. Many people around the world have chosen to do the same. It therefore, I told them, depended on how they chose to make the argument.

I start with these reflections as they show, I hope, some of the difficult discussions that black women’s poetry has brought into the South African classroom.

***

Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2018 is a collection of essays edited by Makhosazana Xaba. It examines the impact that black women have had in the development of poetry in South Africa.

It is an experimental book divided into three sections. The first section contains academic essays, the second is personal essays from South Africa’s leading female poets, and in the last section are interviews with several poets as they reflect on the state of South African poetry.

In the first section Xaba offers an in-depth historiography of South African poetry post-1994 but her focus is on the years between 2000 and last year.

Xaba writes that part of what motivated her to look into this history is a question that was posed by the feminist author and academic, Pumla Dineo Gqola, when she asked: “What do we make of the dramatic shift in who publishes poetry in contemporary South Africa from a handful of recognisable white men and women writers, to a proliferation of Black women poets?”

Xaba’s chapter looks at this shift and argues that this change has been made possible “by the inevitable coalescence of the gains of the three waves of feminism at a critical period in South African history” and “the tectonic social and political change from legalised and institutionalised racism to a constitutional democracy”.

She offers a deeply rich analysis of what has been published by black South African women over the past few years and its thoroughness, I suspect, will serve as inspiration to younger researchers.

Other contributors in this section are VM Sisi Maqagi, Barbara Boswell and duduzile zamantungwa mabaso. In Boswell’s important chapter she interrogates the ways in which black female bodies have been constructed by history and argues that post-apartheid South African female poets have responded to this history by troubling its assumptions.

When she reads Natalia Molebatsi’s poem, Ode to the Vulva, Boswell writes that Molebatsi renames and recalls a “negatively overdetermined sexual and sensual body part” and that “it is through loving this most insulted of body parts – that to which black women are often reduced in order to objectify and dehumanise them – that freedom is claimed”.

Boswell’s essay also asks questions about which bodies are seen as sexually desirable and which ones are not. She argues that if we continue to make some bodies feel marginalised, because of how they appear, then we continue to perpetuate the legacy of the past that was based on placing bodies in hierarchies of importance.

A powerful light is cast on the question of language in mabaso’s essay. She is deeply critical of the ways in which South Africa’s democratic dispensation has dealt with indigenous languages as it seems to have accepted that English will be the dominant language.

She writes, scathingly, that: “There is not enough work being done to make our languages be the languages of self-actualisation. And so indigenous language writers exist in the margins. Treated like temporary languages, used in teaching and learning in early education or as entertainment for tourists when presenting what South Africa is all about.”

The essay by mabaso is a plea to continue using and promoting indigenous languages in all spheres of society lest the colonial legacy is shown to have prevailed. This is a view shared by Vangile Gantsho who says: “We really need to make a concerted effort not to allow our generation to be the reason why languages die. We owe it to our children and our grandparents to preserve all that is beautiful about the people we are.”

***

In the second section of this collection, South Africa’s leading poets reflect on their journeys in becoming poets and on the importance of this genre for them.

What comes out of these personal essays is a story that it too familiar in South Africa – the ways in which misogyny continues to be lethal as it not only structures the opportunities that are made available for black women but it also attempts to tell women how they should write and what they should write about. Some of the names in this section include Myesha Jenkins, Toni Stuart, Sedica Davids, Tereska Muishond, Phillippa Yaa de Villiers, Mashile, among others.

Stuart writes that for her, the power of poetry lies in the fact that: “Poetry allows us to share our weaknesses and to make ourselves vulnerable. Sharing that vulnerability through the act of reading our words out loud allows us to discover our strengths. In turn, when we take up the role of the listener, we hold space for someone else to express their vulnerability and thus step into their strength.”

Says De Villiers: “Being a poet is a privilege, a licence to publicly imagine the world as it appears to us. We are allowed to present the world in a fantastic form, invented by us.” This seems to be particularly important for De Villiers because as an adopted child she “learnt to pretend – to blend in. My childhood was largely characterised by vast silences, absences of words”.

An important historical period in the development of South African poetry is contained in the stories of Jenkins, Ntsiki Mazwai, Napo Masheane and Mashile.

In both their essays, Jenkins and Mashile speak to the origins of their popular group Feela Sistah! Spoken Word Collective that was formed in 2003.

Jenkins writes that the group was born out of the frustration of not being recognised as women poets while at a writer’s workshop in Port Elizabeth.

She writes: “Outside while we were smoking, Ntsiki Mazwai and I were fuming because we were not being called on during discussions and open mics, not being heard in plenaries.”

And this is how Feela Sistah! came into being.

Mashile writes that this group was extremely important to her development as a poet. She says that it “was an enormous breakthrough because it offered a sense of community with women whose work dealt with similar subject matter to my own”.

“Feela Sistah! would liberate me in many ways and would eventually grow into a pop culture force that none of us could have anticipated,” she writes.

***

The last section is of interviews with Diana Ferrus, Mthunzikazi Mbungwana, Nosipho Gumede, Malika Ndlovu and others as they reflect on various issues.

One of the most interesting interviews is with Ferrus whose poem, I’ve Come to Take You Home, has become a classic in South African poetry as its power was responsible for the return of Sarah Baartman’s remains from France.

Asked where she thinks the power of poetry lies, Ferrus says: “Poetry is able to move the heart, poetry can take the reader/listener ‘prisoner’ and work with his/her mind and bring about a different person at the end of the reading.”

When Molebatsi is asked about the state of South African poetry in 2010, she says: “We are not there yet because we still don’t go beyond our local into a global context. Many poets focus on rhyme and not the meaning of each word. Our poetry has to be justifiable and it has to be defendable, word for word.”

Molebatsi’s interview sends a strong reminder that unless the material conditions of the people of South Africa are changed, the possibilities of expanding the number of black female poets in the country will remain limited.

She says: “Poetry is about time and space, and these aspects of life are stolen from you the moment you are born in the township. People yearn still for a bigger and better piece of land.”

Our Words, Our Worlds is a timely collection and it is without a doubt, as the acclaimed poet Gabeba Baderoon writes in her introduction, “an instant classic”.

It is one of the most important books to come out of South Africa and it will, for the foreseeable future, be a treasure trove that will inspire many writers.

Most of the essays in this collection attest to the fact that South Africa’s constitutional democracy was hard-won despite the enormous challenges it still faces.

If the racialised economy and the vicious misogyny that greatly impact on black women’s lives continue, the poets declare, they will be here to bear witness.

Nthunya is a PhD candidate in literature at Wits. He studied literature, history and philosophy at Rhodes University

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners