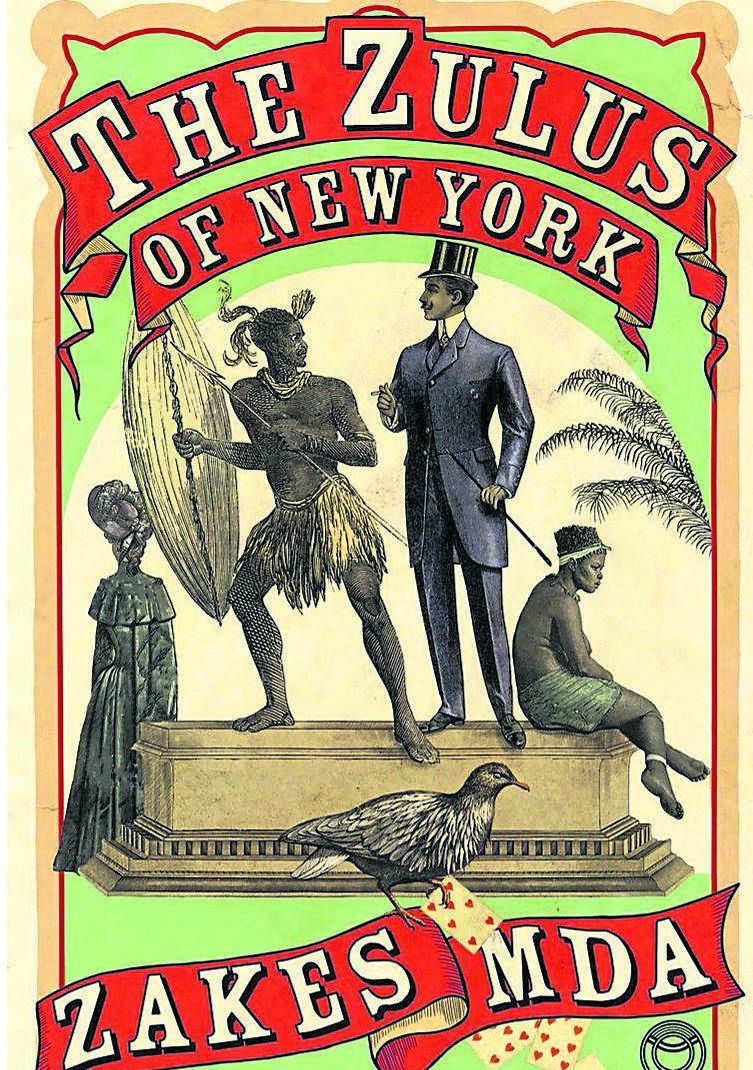

Zakes Mda’s latest novel, a devastating tale of the display of black bodies for white amusement, was launched last week. It is also a subversive work; a retelling of history that is steeped in humanity and wit. Charl Blignaut sat down with him

Was there really a human curiosity called the Daughter of Hottentot Venus who went on display more than 100 years after Sarah Baartman?

Did the Zulu King Cetshwayo really wear a black overcoat with red trimmings to go to the toilet while being guarded by women?

Was there really a late 1800s trend called slumming, where the rich dressed in rags to take a holiday in the ghetto? Were the Zulus honestly the Kardashians of their day, a buzzword in popular culture?

The answer to all of these questions is yes. Painter, playwright and novelist Zakes Mda chuckles when I ask the questions.

“Well, of course. I don’t invent history,” he says with that characteristic twinkle in his eye.

He may not have invented the historical truth of the performing Zulus in the human circuses of London and New York in the 1800s, but he does retell it from the position of the previously silent black bodies that occupied it.

When we meet in Johannesburg the day after the launch of The Zulus of New York in Pretoria, he lights up when he sees me and opens his arms for a hug – he’s a man with an ability to make anyone his friend, and one who constantly deflects the attention from his writing to your reading.

I have done many interviews with the nation’s favourite literary uncle, and I know that you can ask Mda anything and he’ll answer honestly and frankly.

You can ask him about Ramaphoria and chest-beating red berets, about corruption and bee farming and toxic masculinity, and he’ll give you his frank answer. But I want to ask him about his new book, which has enchanted me since the cover was revealed and which I finished reading the night before.

The human circus

The Zulus of New York begins in 1878 in KwaZulu-Natal with our hero Mpiyezintombi “Battle of the Maidens” Mkhize, a right-hand man to King Cetshwayo, who will find himself cast from the kingdom.

In 1880, Mpi arrives in London and is called Em-Pee, a Zulu performer in the pseudo anthropological circus of impresario, inventor and tightrope walker The Great Farini.

Em-Pee never dreamt of a life amid the Two-Headed Nightingale and the Dwarf Earthmen, and he will never be satisfied with it.

In 1885, he finds himself in New York, where his life changes forever the moment he sets eyes on Dinkie the Dinka Princess in her cage – on display, a curiosity. She is owned by Monsieur Duval of Duval Ethnological Expositions. She is a slave, even though slavery was abolished in the US in 1865.

The Zulus of New York contains, like all of Mda’s novels, an epic love story.

It is, like all of his novels, ultimately the story of the artist as an outsider. The artist who calls whales, the supernatural sculptor of Mapungubwe, the man who adopts the art of mourning. And, like all of his novels, its humanity rises to the top of the stinking pile of history.

Little Suns was an exploration of your family history. But how did The Zulus of New York manifest in your research?

Well, this one came about when I read an academic paper on the Zulus in New York and that phenomenon.

Because it was a huge pop culture phenomenon, The Great Farini and so on. The scholar was a friend of mine, Bob Edgar. And I thought, oh, that’s so interesting to explore.

So you read up on Farini?

Who was born William Hunt in Canada, in his own right a great circus performer who, on a tightrope, walked across the Niagara Falls.

He used to perform with the Flying Farinis. And he came to Cape Town and explored into the interior of South Africa to the Karoo, and came back and said he had discovered the Lost City of the Kalahari, which he wrote long tracts about.

He was a man of inventive character. He was creative, you see.

And then, of course, he would take a few Bushmen, or Hottentots as they were called then, back to England to be part of a human curiosity display and he would create biographies for them.

Just like reality TV today. You create biographies for these real-life characters, that is why you even had the daughter of Sarah Baartman there and audiences lap it up.

He introduced Zulus to the repertoire?

After the Battle of Isandlwana [in 1879], there was this explosive publicity in England. I’ve looked at the newspapers of the time. Especially the London Illustrated News, which was one of the glossies with painted illustrations.

So, after Isandlwana, there were explosive images of these savages who had defeated the greatest army in the world from the biggest superpower in the history of the world.

Farini saw the chance – if I bring in some proper Zulus or some black people from Africa and dress them up as Zulus, I’ll make a lot of money. And he did.

Friend or foe

The line between the ferocity and the friendliness of Mda’s Zulu troupes is a balancing act throughout the novel.

Em-Pee cannot abide pretending that the Zulus were flesh-eating savages with enormous penises, roaring for blood.

He is happier to starve for the sake of authenticity, wanting to display the beauty of Zulu dances and songs. This brings him into conflict with the circuses that can put bread on his table. Through Mpi’s unsensational eyes, we learn of his history.

How do you approach the histories that you retell?

As I was explaining to my audience last night, there are two dominant types of historical novels.

There’s the one where the author tries to subvert history, the postmodern historical novel that reimagines history.

And when you read that novel, you know exactly what the writer is doing – it’s great fun, you take history in a direction you think it should’ve gone rather than the one it actually did take. There’s that writer.

I’m not that writer. I’m the one who wants to be true to historical record and not change anything that is recorded as having been the history.

Why? Because my intention is more than just telling the story, it is also to highlight that history; to teach history in a more entertaining manner.

So it’s important that my reader should know I have thoroughly researched that.

But, most importantly, it is to tell history from a different perspective – a new perspective – because the history that you usually get in history books is the story of the dominant classes, and that writing of history is driven by the dominant classes, be it the colonialists or the ruling classes.

It is the story of the victor, as you have often heard.

But I am more interested in looking at it from the perspective of the ordinary people who were affected by those events and even drove those events, instead of telling it from the perspective of the general or the king. Instead, I am telling it from the perspective of the soldier.

The thing about this is the black retelling of a dominantly white narrative.

It was important for me to give that anonymous Zulu dancer a voice. They were there – we’ve seen their pictures – but we never got to know who they were.

Okay, we got to know some of them, like Zulu Charley, the one who married an Italian girl.

Very few of them have a biography and even then his biography only begins when he’s in the US and he falls in love with this Italian girl and the New York Times writes about it.

When they write of the Battle of Isandlwana, they are telling the grand narrative.

“And then they appeared from this flank and from that flank and the commander was so-and-so and the colonel of the British was so-and-so.”

But it isn’t about the human beings who were involved there – what they eat, what they do on a daily basis.

My stories are about the mundane; they are about the king going to sh*t. I had to research all that.

Fortunately, there is material that people have ignored. For instance, there’s a woman called Paulina Dlamini, who was one of the girls in King Cetshwayo’s isigodlo – these harems that the kings have.

She grew up there and observed all these things, and then later on, after Cetshwayo was defeated by the British, she joined the missionaries and became a Christian and learnt how to read and write.

Then, with the assistance of a missionary, wrote her story. So her biography is published by UKZN Press.

But your two lovers are fictional characters.

My two lovers are purely fictional, but created from what used to happen. There were the Dinka women who would be kept in cages because of their exotic features. They are tall and dark and sinewy.

There were Zulu dancers dancing there. All I did was give them biographies from the lives of the time.

Just like reality TV

Mda’s novel is theatrical – it’s all about display and performance, a clear extension of his playwrighting skills.

In fact, some theatre producers have already approached him about turning The Zulus of New York into a play.

And Channel 4 in the UK has been in touch about a miniseries. It’s perfect for the pop of our time.

There are heavy histories weighing on Mda’s story – stolen land, colonial plunder, slavery – yet he delivers his tale with a light and often witty touch, the writer as trickster.

We talk about the weight of history and the politics of his tale. But Mda is not focused on politics, he is interested in telling a story of human beings.

Politics enters the universe organically, by the nature of who his human beings are and the space they find themselves in.

I was astonished by the bit where you write about the slummers – rich English who dress in rags and stay in the slums as a kind of poverty tourism combined with sex tourism. And also how the upper classes start coming to the circus displays.

Yes, the slummers were after pure poverty porn. It was extremely popular in those days. And when these human curiosities started, they were for the common people.

The higher-class people went to concert halls and opera houses, and that was their thing.

People like Farini changed it all. He’d add an academic spin, like Darwinism. Survival of the fittest was a popular theory and they’d bring these primitive people and animals as well, marmosets and whatnot, in cages, and they’d give talks.

Some very nebulous Darwinism – a lot of it invented to make it all the more dramatic.

They even invented stories of how these people were captured and said that they were a prince of some island; creating fake biographies.

This made it attractive even for the higher classes. Darwin was part of pop culture like the Zulus.

It’s no different from what we see today. It’s “social experiment reality TV”, like Married at First Sight – it’s not a social experiment, it’s an exploitative and rigged reality show. There’s this wonderful moment in the book where we meet a large mixed-race man called Mr Dominic Alef, who has created himself as The Wild Zulu.

And even that happened. A lot of people from New Orleans paraded as Zulus.

In fact, New Orleans continues with that tradition to this day. You go to Mardi Gras and there’s a whole team of New Orleans Zulus in blackface.

Well, they’re already black people who then blacken their blackness further. So the Zulu troupe there has its origins in these performances I write about.

Read: Book Review: The Love Diary of a Zulu boy

The wisdom of the Dinka

Mda’s love story in The Zulus of New York is perhaps his most epic yet – and that’s saying something. Mpiyezintombi as very much the lion, the earth. And Acol represents fish and water. They come together like planets really to form a whole. It’s an epic pairing.

Mda almost claps his hands with delight when I tell him I read the characters this way. He calls it a beautiful reading and, once again, denies it has much to do with him – saying it is up to his characters, who he created with practical purpose.

Towards the end, The Zulus of New York takes a profoundly spiritual turn. Again, the great writer shrugs with a twinkle in his eye. It isn’t him who should get the credit, he says.

The book, ultimately, is a bold attempt to restore dignity to black life.

The Dinka people of the Sudan have a philosophy, or even a religion – because sometimes with Africans, you can’t distinguish between the two – which is centred on dignity.

From the time the child is born, their goal is that this child should attain dignity, especially through their initiation into manhood and womanhood. And, for them, dignity has an aesthetic, it is a performative thing.

So I was impressed by that because I’m writing about two human beings who have been dehumanised.

Where should they get their power and their strength back? Ah! Fortunately, the Dinka have the answer, which is their philosophy of dignity.

Thus, then the woman teaches the man because they don’t have that where he comes from.

He has a philosophy of ubuntu, which is quite different, which is why the woman is not freed by the man but uses her own resources to liberate herself even within captivity and she teaches the man to free himself. So it was for those practical reasons.

It was very important that this woman must not be rescued by this man. I wanted her to liberate herself using her own inner resources.

Then her possession, really, her jok, becomes her weapon. The thing that was making her ill is transferred to an anger that can help her heal. It’s very profound. You have lines like “a god can only control the people who created the god”. It’s quite a big and wonderful statement.

And, by the way, that’s not my thought, that’s the Dinka. It sounds like a sophisticated philosophical thought I had. Well, I believe in that too, but just incidentally. The Dinkas actually express it in those terms.

And it has a catch that, even if it has a happy ending, they will never be together. Are your lovers ever together? They were in Ways of Dying.

I don’t remember Ways of Dying. It was so long ago. But I do remember Little Suns. They were together because they walk together to the stars, they climb the mountain and jump from star to star together.

In this one, I am actually telling you it has a happy ending because it’s so easy for someone to interpret it as a sad ending because those lovers do not sail together into the sunset.

No, no, don’t be sad, be happy. They have overcome.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners