As Speaker Jacob Mudenda finished reading Robert Mugabe’s resignation letter, the response was deafening. The members of the two Houses rose as one in instant celebration, with dancing and cheering. The ousting of Robert Mugabe as Zimbabwe’s president took the world by surprise. In this book, veteran Zimbabwean journalist Geoffrey Nyarota explains how and why the events of November 2017 happened as they did.

In the early evening of November 19 2017, the first stages of President Mugabe’s highly anticipated resignation were somehow both drama-filled and anticlimactic.

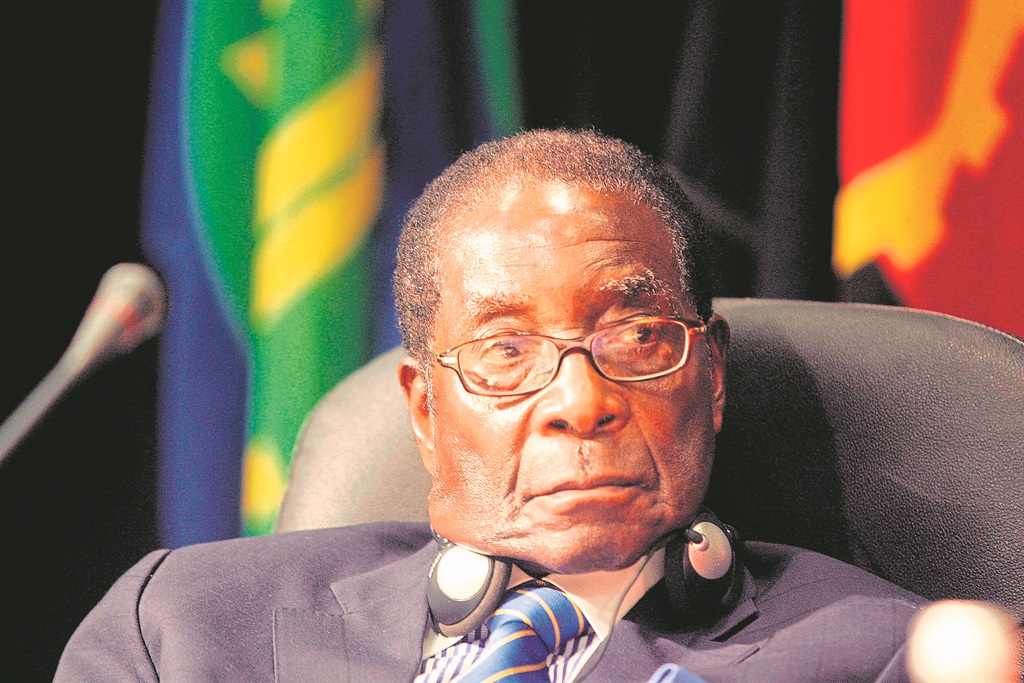

On the day of his final reckoning, this widely feared and supposedly untouchable leader had not cut much of an impressive or fearsome figure.

He was led into a prepared room at the State House, almost like a sheep to the slaughter.

There, he slumped rather pathetically into the chair reserved for him at the solitary table.

Dwarfed on either side by the imposing figures of General Chiwenga to his right and Father Fidelis Mukonori, who had become a constant companion and adviser to the president, to his left, Mugabe simply focused on the papers before him.

He hardly dared to raise his head. Gone was the customary confidence, bordering on defiance, that had become both his practice and his trademark whenever he addressed the nation, sometimes for several hours on end.

Arranged on the table, waiting to spread his words around the world, were two ancient-looking microphones, one of them from the notoriously compliant state broadcaster, which was now under military control.

Otherwise, there was only a single ZBC television camera.

The rest of the media, comprising a burgeoning contingent of local and foreign journalists who had descended on Harare like vultures to document the dramatic turn of events, were prohibited from entering the State House.

As a result, the event’s coverage was rather spartan despite the historic weight of the occasion: Mugabe was expected to resign as president of the country, commander-in-chief of the ZDF, president and first secretary of Zanu-PF, and chancellor of Zimbabwe’s state universities.

The atmosphere was tense. But as Mugabe sat there before the television camera, it struck me as incomprehensible that Zimbabweans had ever been petrified of him at all.

After so many decades, he looked like any other harmless old man – vulnerable and perhaps a little frightened.

In reality, though, it was the men lined up to Mugabe’s right who had instilled such fear among the people on his behalf. Now those generals had turned on Mugabe.

Next to General Chiwenga sat Zimbabwe’s security chiefs. They included Dr Augustine Chihuri, commissioner general of the Zimbabwe Republic Police; Lieutenant General Philip Valerio Sibanda, commander of the ZNA; Air Marshal Perence Shiri, commander of the Air Force of Zimbabwe; and Commissioner General Paradzai Zimondi of the Zimbabwe Prisons and Correctional Services.

Standing at the far right and striking a rather dissonant note in civilian garb was the acting director general of the CIO, Aaron Daniel Tonde Nhepera.

On the other side, by Father Mukonori, were Dr Misheck Sibanda, the long-serving chief secretary in the Office of the President and Cabinet, and George Charamba, the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Information, Media and Broadcasting Services, who served as the official spokesperson for President Mugabe.

It was the same Charamba who had only recently been castigated in public by Grace Mugabe during her rally in Bindura.

Members of the public who were anxiously watching on television were expecting a succinct statement by the president that he was finally resigning from office.

His years in power had been tumultuous and excruciatingly painful for the majority of Zimbabwe’s ordinary citizens.

More than three decades of dire economic decline had resulted in a dwindling availability of everyday goods, not to mention serious cash-liquidity crises in banks and other financial institutions.

They were years characterised by the ostracisation of Zimbabwe from the international community.

As Mugabe prepared to read, there was a moment of embarrassment as he fumbled with the sheets of paper in his hands and some detached themselves, only to be quickly rescued by General Chiwenga, who leaned forward to retrieve them from the floor.

Quite astonishingly, rather than returning them to the president, he handed the papers to Dr Chihuri, who accepted and held onto them. The reason for this odd exchange has remained a mystery.

But the often voluble ZNLWVA later claimed that this small act of clumsiness was no accident.

There were reports that the fallen papers retrieved by Chiwenga had been the president’s letter of resignation. It was thus alleged that Mugabe had used the opportunity to discard his speech in order to avoid delivering it.

When he was sacked as leader of the Zanu-PF party the previous day, a Saturday, Mugabe had been given until noon on Monday to resign as head of state.

If he did not, he would face the risk of being impeached when Parliament, then on recess, reconvened on Tuesday 21 November.

With this deadline in place, Zanu-PF published a draft impeachment motion. The draft stated that Mugabe had become a ‘source of instability’ and had shown disrespect for the rule of law.

It also placed the blame for Zimbabwe’s economic nosedive over the past fifteen years entirely on Mugabe’s shoulders.

While the nation expected him to steel himself and reward them with his instant resignation that Sunday evening, Mugabe proceeded, much to the consternation and chagrin of those watching him, to read a statement that was tantamount to a routine State of the Nation Address.

The event struck most as a colossal disappointment. In his final televised speech to the public, Mugabe had not even offered significant concessions to a nation of anxious citizens.

Among the most disappointed, however, were the army generals who had orchestrated the military takeover during that week.

All that millions of people had hoped to hear was a simple declaration: ‘I hereby tender my resignation from the position of president of the Republic of Zimbabwe.’ Instead, there Mugabe sat, glum and nervous, a mere shadow of his reputation, with his eyes fixed on the papers now neatly arranged for him to read.

The idea that his speech had been swapped is certainly not implausible. It was suggested by those who appeared to be in the know that there had been a last-minute realisation that the president, in terms of Section 96 (1) of Zimbabwe’s Constitution, could only resign by tendering a letter to the Speaker of the House of Assembly. Simply having him read a statement to the nation would not be legally or constitutionally binding.

In fact, Chiwenga had hinted as much when he revealed that negotiations had gone well between the generals and the president, and that Mnangagwa was on his way back to Harare from his brief exile in South Africa.

Chiwenga had correctly pointed out that it was not the responsibility of the military to announce the resignation of the president to the nation.

This might explain the withdrawal of Mugabe’s papers and their concealment by Chihuri, which left the president looking uncharacteristically unsure of himself.

During his twenty-minute speech, Mugabe merely acknowledged that Zimbabwe was a country beset with problems. And to the utter astonishment of all who were watching, he vowed to soldier on. ‘The era of victimisation and arbitrary decisions must end,’ he said.

Unbelievably, Mugabe went on to declare that he would preside over the forthcoming Zanu-PF congress, then a few weeks away in December, despite the fact that the party’s Central Committee had dismissed him as president and first secretary just a few hours earlier.

‘I will preside over its processes, which must not be prepossessed by any acts calculated to undermine it or to compromise the outcomes in the eyes of the public,’ Mugabe maintained. He did not explain how he intended to oversee the congress if he was no longer the leader of the party.

Since it was patently clear that Mugabe had no intention of resigning from office that Sunday night, the nation’s focus became riveted on the noon deadline the following day. Yet it came and went, and the president had still not provided his resignation.

The House of Assembly immediately started to galvanise for a final onslaught on Mugabe through impeachment.

Mugabe’s first encounter with trouble on Tuesday 21 November was a general boycott of that morning’s cabinet meeting. Only three ministers, Michael Bimha, Joseph Mtakwese Made and Edgar Mbwembwe; chief secretary to the president and cabinet, Dr Misheck Sibanda; and Attorney General Prince Machaya showed up. Mugabe had convened that particular meeting at the State House instead of in the usual cabinet room at Munhumutapa Building.

That same morning, upon his arrival back in Harare, Mnangagwa issued his first statement. He implored the president to take heed of what he called the insatiable desire for change by the country’s population.

‘The people of Zimbabwe have spoken with one voice,’ said Mnangagwa, ‘and it is my appeal to President Mugabe that he should take heed of this clarion call and resign forthwith so that the country can move forward and preserve his legacy.’

Later in the afternoon, lawmakers from both Houses of Parliament, reinvigorated by the events of the past week, assembled in the Harare International Conference Centre, which was large enough to accommodate the joint sitting.

They proceeded to go through the formalities of pushing forward the impeachment motion.

Among Mugabe’s alleged flaws that were cited were his falling asleep in public during meetings and permitting his spouse, Grace Mugabe, to “usurp presidential powers”.

The motion was tabled by Senator Monica Mutsvangwa of Zanu-PF and seconded by James Maridadi of the MDC-T, the main opposition party.

But Mugabe, who remained a cunning politician to the end, scuttled the whole process. Amid proceedings, an usher hesitantly walked into the hall and approached the Speaker, Jacob Mudenda.

While handing over a letter, the usher mumbled a short message. Although his voice was too soft for onlookers to hear, the meaning of the exchange was obvious. His Excellency, President Robert Mugabe, had finally resigned.

The timing of the letter’s arrival effectively denied the honourable members their first and only opportunity to humiliate Mugabe through impeachment, as they had been busy planning to do.

The members erupted in celebration as Speaker Mudenda went through the process – perhaps a mere formality in the circumstances – of reading out the president’s resignation letter.

What follows is a transcript of that letter as it was read to the joint sitting of the senate and the House of Assembly:

On that sombre note, Mugabe’s reign – characterised by over three decades of political intimidation, violence, gross abuses of human rights, deprivation through shortages of basic commodities and the inadequate provision of essential services – drew to a close.

As Mudenda finished reading Mugabe’s letter, the response was deafening.

The members of the two Houses rose as one in instant celebration, with dancing and cheering.

- The graceless fall of Robert Mugabe will be released soon. You can order it here.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners