S’bu Mngadi recalls an incident during the politically turbulent 1990s when a murderous intruder to the City Press offices revealed odd flashes of humanity in his brutality.

The late-afternoon knock on the door was rapid and agitated – reminiscent of the security police’s predawn raids that, for many, had led to death, disappearance or torture. I was alone in the City Press offices in Durban, on the fifth floor of West Walk on West Street, the coastal city’s it-street before current inner-city decay. I was on standby for breaking news and last-minute fact-checking for the next day’s paper.

The knocker’s urgency piqued my journalistic interest for a potential scoop. Unlike the local old establishment press owned and led by English gentry, City Press had from 1983 earned itself must-read status in the urban areas of (then) Natal, which was and is still the “last white outpost”.

Nonchalantly, I yanked the thick door open, leaving the locked Trellidor gate to separate me from the knocker.

Cursing my cowardice under my breath, I unlocked the steel gate and shuffled backwards until I fell on to the brown L-shaped couch in the reception area. The knocker did not miss a step and walked lockstep with me as if we were dancing, with the firearm still pointed at my chest.

Why my chest? The head is usually a shooter’s target of choice. The knocker stood commandingly over me while I half-sat, half-lay on the edge of the couch. The office telephone was a metre away. However, my potential death was nearer.

It was public knowledge that the knocker had killed several activists and their family members, as well as ordinary citizens, in Durban and surrounding towns. His signature method of murder was sticking the muzzle of the gun into the victim’s mouth before pulling the trigger, which often caused decapitation.

He was curious. Why was I making it my mission to report on his killing spree (which he called his “life”)? What was in it for me? He sought to know the journalist behind the byline. It was bizarre for a killing machine to suddenly care about the humanity of his soon-to-be victim. Killer-cum-sociologist?

In the haze of extreme shock, I begged the muzzle (not its holder) to allow me to grab a notebook and a pen from the reception desk, and he obliged.

I captured my “obituary” in shorthand and orally contemporaneously. I was in a near-semiconscious state.

READ: Sarafina to air on e.tv on Youth Day for 30th anniversary

My still tender life flashed before me like minidisks in a 1990s slide projector:

- Multiple forced removals of my paternal and maternal grandparents, descendants of landed Africans in the Natal Midlands;

- 1976 uprisings that inspired my political consciousness at the age of 10;

- Growing up in Clermont;

- Singing in a church choir;

- Youthful indiscretions: love, crushes, losing my virginity;

- University of Southern California (USC) days;

- My mom, an industrious woman. (Had it not been for ANC ineptitude and policy flip-flop on land reform, she and her living siblings would have reclaimed large tracts of ancestral land, including parts of the N3 between Ladysmith and Estcourt);

- Buying my mom a new house, using City Press’ generous two-year study leave salary while I was at the USC’s School of International Relations;

- The struggle, which it was the duty of every youth in Clermont to support; and

- House and student parties.

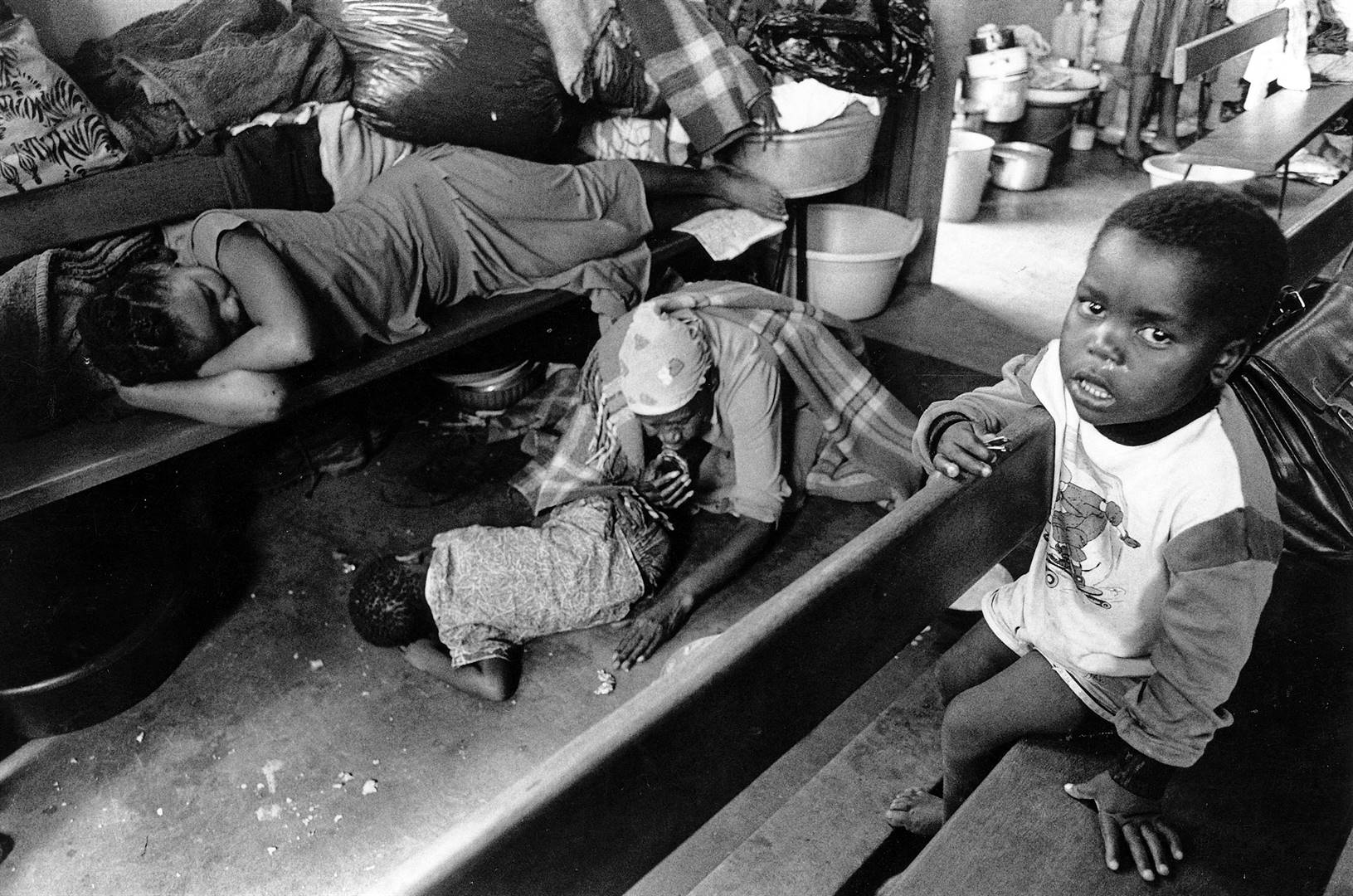

Finally, I reflected on Natal’s civil war, which had been under way since 1985 between Inkatha and the United Democratic Front (UDF) – ironically, a formidable and better organised proxy of the ANC.

Inkatha was funded by the military intelligence of the SA Defence Force (SADF) and the security police of the SA Police (SAP), which trained and weaponised the party’s members.

UDF self-defence units benefited from ragtag training provided by Umkhonto weSizwe cadres, the movement’s arms caches and supplies from (then) Swaziland, Mozambique and the erstwhile Transkei Defence Force. (By the time the civil war ended in the late 1990s, it had claimed 30 000 lives.)

One of this civil war’s protagonists – lauded by Mangosuthu Buthelezi as a “great shot” – was now about to take my life. The youthful, fit and bizarrely likeable Siphiwe Mvuyane seemed more fascinated by my shorthand than by my “obituary”.

I challenged him to remove his mask and tell his own story. The response was chilling:

My colleagues would find my notebook and publish the interview posthumously, I retorted. He would burn my notebook, he declared angrily, reasserting power relations in the death chamber.

Thanks to the brain fog of shock, I no longer recall the word I uttered to trigger Mr Evil to open up – but he did. It was gory. Heart-wrenching. Bloody.

In summary, he had been selected from the best of the recruits for specialist military training by the SADF’s military intelligence and the SAP’s security police.

On their deployment in Natal, there had been unparalleled mayhem in the province, which was already steeped in blood. Occasionally, the killing squads Mvuyane commanded went on “weekend kill missions” in Gauteng (then known as the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vaal triangle).

Our conversation included some awkward moments. Mvuyane vigorously protested my tally of more than 50 people killed by him. He said his “record” had not exceeded 20 deaths.

The image that haunted me of his killer squad’s grotesque handiwork was a mother with a six-month-old daughter strapped to her back in Upper Edendale, Pietermaritzburg, during the “seven-day war”.`

The conversation reached a turning point. Extreme exhaustion simply overcame me.

Should I tell him the interview was over, at which point he would shoot me, or should I keep him talking? The 51-minute encounter had zapped the life out of me. Holding a pen was a struggle. I ended the interview and the notebook fell to his feet.

I spoke, but did not produce words. He put his gun into its holster and half attempted to hug me. That gesture exposed a colostomy bag on his left hip – a reminder of a recent kill gone bad.

Mvuyane took charge. There was only one bullet in his gun’s chamber. If the first four shots failed to fire, the fifth one would be my “lucky bullet”, which would be his “gift” to me.

He made me stand against a white wall. I was frozen. My skin had turned greyish and my body was numb. I struggled to stand erect as Mvuyane stepped back.

I held my falling forehead with my right hand and put my other arm across my chest, as if to shield myself. I closed my eyes. I heard several bangs. Then a huge bang reverberated around the office, leaving me partially deafened.

However, no part of my body had been injured. When fragments of cement fell on me, I realised the killer cop had fired above my head. “That,” Mvuyane laughed, “was your lucky bullet.”

READ: WATCH | Short film to commemorate Youth Day

He collected the spent bullet and its casing and exited office 501 in West Walk, using a sheet of newspaper to open the door.

His parting words were to sarcastically advise me to install CCTV cameras outside the offices. City Press relocated to more secure offices a few months later.

Dazed, I called the news editor, who might have been Len Kalane or Charles Mogale – I no longer recall. I told him I had survived an assassination attempt by the notorious killer cop. I could hear the editor telling the subs desk that he had a “riveting” story of S’bu’s encounter with the killer cop.

In another world, my first call would have been to the police. But trust in security forces was nonexistent.

However, I called a family friend, Warrant Officer Wilson Lwandle Magadla, who drove me home. (Magadla’s pioneering investigations would prove the apartheid state’s central role in post-1990 black-on-black violence.)

I had a second violent encounter with Mvuyane and his goons. This time, I fought back ferociously, inside and outside Whispers nightclub.

Mvuyane’s state-funded killing campaign continued with impunity. He was arrested on May 14 1992 in connection with a cache of weapons manufactured by Mossberg & Sons of Connecticut, US. However, the case never went to trial because magistrates and prosecutors feared reprisals from the apartheid government.

Mvuyane eventually died in a gun attack during a party at the then University of Durban-Westville on May 1 1993.

READ: Fred Khumalo: Reporting from the frontline was a blast

Following the office attack, I stayed at City Press for another 17 months before relocating to Johannesburg to join the pioneering black-excellence magazine Tribute as deputy editor and later editor.

Before my transition, I heeded sage management advice to “hire a successor who’s miles better than you are”. Consequently, I recommended Fred Khumalo, and City Press’ management approved.

In 1996, I joined the Coca-Cola Company’s southern African division as vice-president and director of communications, public policy, sustainability and governmental relations. The position led to my working around the rest of Africa and in the Middle East.

In 2000, I relocated to Coca-Cola headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, US, as global vice-president and director. Despite taking a four-year break from the company, in total I served it in Africa and North America for 13 years. Since then, I have served other multinational companies in various executive roles across North America, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East for 14 years.

It all began at City Press in 1984 as a cub reporter with boundless dreams.

Mngadi was a reporter and bureau chief (regional editor) in Durban from 1984 to 1993. Currently, he is a partner in a leading global advisory corporation, headquartered in Paris. He writes in his personal capacity

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners