Hero of Zambian football Kalusha Bwalya enjoyed life at the top of the sport, but was brought down by greed, writes Ponga Liwewe.

To his legion of worshippers, he is known as “King Kalu”.

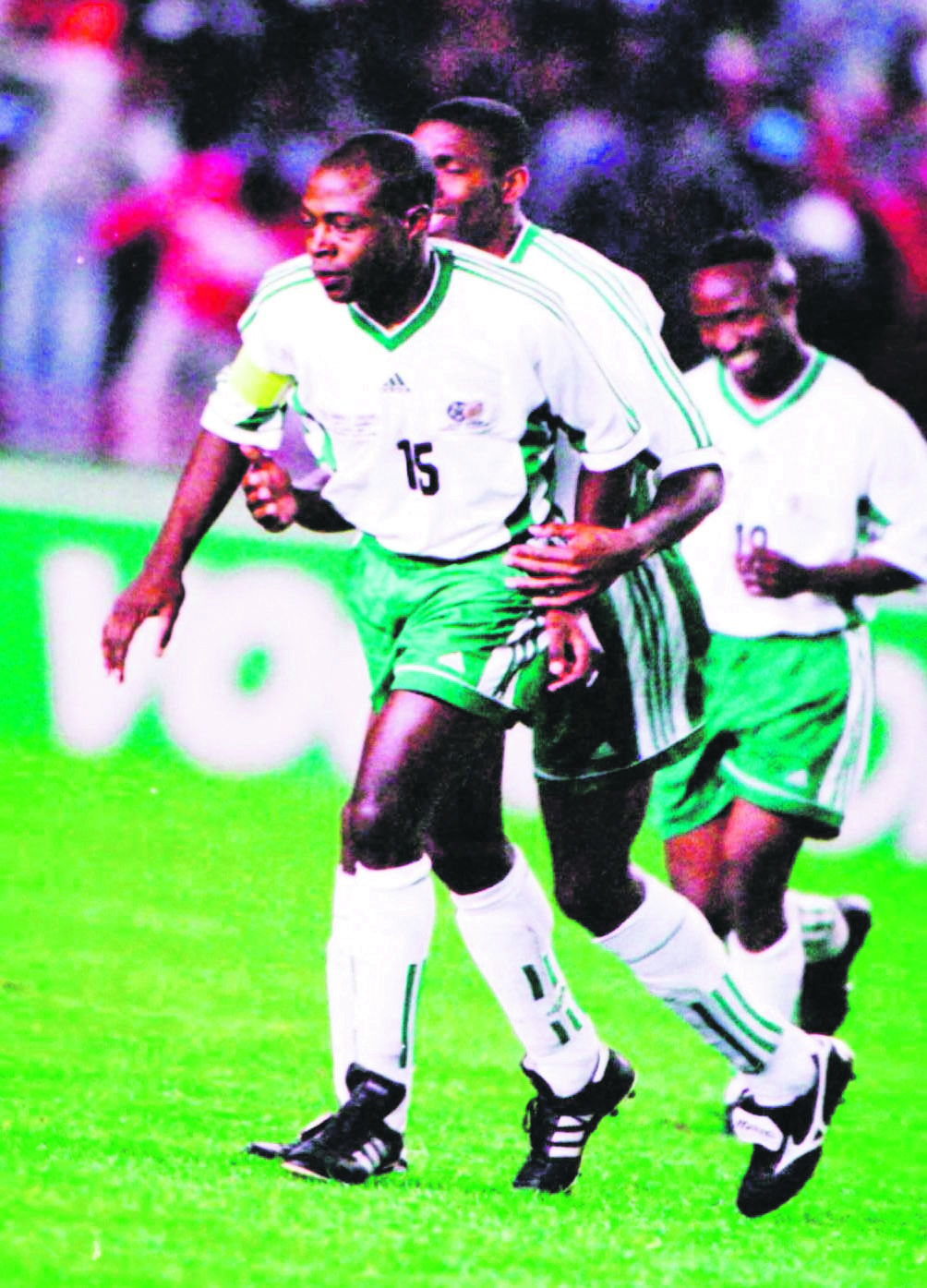

In Zambian football, his status is unchallenged as one of the top players in the country’s illustrious football history. His CV is littered with stories of success – African player of the year in 1988 and top scorer in the 1996 Africa Cup of Nations. These are just two of the accolades Kalusha Bwalya won during his years on the pitch.

On August 10, the king lost his crown. The adjudicatory chamber of Fifa’s ethics committee released a statement announcing a two-year ban and a fine of 100 000 Swiss francs (R1.4 million) for breaching Fifa’s code of ethics.

Fifa’s decision was the culmination of an investigation by the UK’s Sunday Times newspaper, which published an exclusive story highlighting corruption around the Qatar bid for the 2022 World Cup. The lead player was Mohamed bin Hammam, a one-time confidant of now disgraced former Fifa president Sepp Blatter.

The UK Sunday Times Insight team carried out a comprehensive investigation that included gaining access to Bwalya’s emails, which contained damning correspondence between him and representatives of Bin Hammam, from whom he was requesting financial support for himself and the Football Association of Zambia (FAZ).

“As per our conversation, please Mr President, if you could assist me with about $50 000 [R711 223] for my football association and personal expenditures. I hope to repay you in the near future, as the burden is a little bit too hard for me at this moment,” he wrote.

The “little bit too hard” burden prompted him to make a further request in 2011 as he declared himself “a little thin on resources”. This was followed by a payment of $30 000. The earlier $80 000, it should be noted, did not get to the FAZ’s account.

To understand how he got himself into this situation, it is necessary to go back to the beginning – to when his football journey began five decades ago in the dusty streets of the mining community of Mufulira in northern Zambia.

His father, Benjamin Bwalya, was a football official who later went on to become a committee member at the FAZ. He was instrumental in getting his talented sons into the football limelight.

Kalusha’s football journey took him from the city council team, Mufulira Blackpool, to the more prominent mine-owned club Mufulira Wanderers. He flourished there and, while still in his teens, was wearing the colours of the Zambia national team.

By 1985, at the age of 22, he had outgrown Zambian football and made a move to mid-level Belgian side Cercle Brugge, where he quickly became the club’s best player. Three years later, he led the Zambian team at the Olympic Games in Seoul, where he emerged as the second-highest scorer with six goals, just one behind the fabulous Brazilian Romário.

His performance in Seoul saw him signed on by top Dutch side PSV Eindhoven, where he initially struggled to make an impression before gaining more playing time under Bobby Robson. After Robson’s departure, he was deemed surplus to requirements and was part of a purge of senior players when Aad de Mos took over. At 30, the prospects of playing for another European club diminished. He then joined Club América, one of the most popular teams in the Mexican football league. The change gave him a new lease of life and saw him become a cult hero there.

To fans in the terraces, he could do no wrong. Off the field, however, relationships with his team-mates and others were not smooth sailing. After his move to Europe, he became more aloof from his team-mates in the national team, and he began to make demands on the team management and association that were, at best, questionable. He demanded a single room while the other players paired. On at least one occasion, his first wife Erica joined him in the team camp during preparation for a crucial match. Bwalya also insisted on receiving extra payment whenever he played for the national team for what he termed a “loss of wages”, even though the clubs he played for paid his salary when he was on national duty, as was the norm.

More disturbing was his antagonistic attitude towards the equally successful Charly Musonda, who had followed him a year later from Mufulira Wanderers to Cercle Brugge as a 16-year-old precocious talent. After one season, Musonda transferred to the Belgian and European giants Anderlecht, leaving Kalusha in his wake. This irked him and matters came to a head when the two differed in front of the nations’ cameras over whether the Zambian national team should continue to play matches after the horrific Gabon air crash, which killed 18 of the team’s players.

Musonda’s position was that Zambia should take a long break to rebuild and, as he made his point, he was sharply interrupted by Bwalya, who retorted: “What do you mean we should stop? We have to go on!”

Two decades later, when Musonda’s three sons began to make an impression on the football stage, their reluctance to appear for Zambia’s junior team was linked to the fractious relationship between the two and, considering the fact that Bwalya was the president of the FAZ, Musonda’s caution was understandable.

At the 2000 Africa Cup of Nations, the Zambian team split apart over a bonus dispute. The overseas players, led by Bwalya, shared $50 000 carried as bonus money, leaving out the local players who were in the majority. This caused unrest, leading to a player strike that was only averted at the last minute. Goalkeeper Davies Phiri flatly refused to play and was replaced by the ineffectual Emmanuel Mschili, who conceded twice in a 2-2 draw with Senegal. Zambia left the tournament at the first hurdle.

After the match, Bwalya announced his retirement from international football. At 36, the curtain had finally fallen on a career that spanned 19 years. He would return for a brief appearance in 2004, featuring in a World Cup qualifying match against Liberia in which he came off the bench towards the end and scored a thunderous free kick, bringing the crowd to its feet in jubilation. All this would be undone a few weeks later, when, in the final of the 2004 Council of Southern Africa Football Associations (Cosafa) Castle Cup against Angola, he was the only player to miss a penalty in the shootout, giving Angola a 5-4 win on Zambian soil. For the first time in his extraordinary career, he was booed by disappointed fans as he left the pitch. It was the last time he would kick a ball as a competitive player.

In 2003, he was drafted into the South African bid for the 2010 World Cup by organising committee chief executive Danny Jordaan. He brought Bwalya into the fold as an ambassador, but would pay a hefty price as Bwalya later actively campaigned against Jordaan in his attempts to become a Cosafa and Confederation of African Football (CAF) committee member. Bwalya’s disdain for Jordaan began even before his outspoken second wife, Emy Casaletti, left her marketing role at the 2010 World Cup bid committee after a mixed performance in her portfolio.

After the successful World Cup bid, Bwalya switched his attention to local football politics and was voted in as the vice-president of the FAZ. His four-year term was marred by open warfare between him and the association’s president, Teddy Mulonga.

In 2008, Bwalya stood against Mulonga for the presidency and swept him aside in an election that was rife with vote buying and intimidation. It was the beginning of an era that would see a lack of accountability, factional fighting and mismanagement.

Nothing illustrated this more than the ill-fated national team trip to play a friendly match against Ghana in London, when only eight Zambia national team players made the trip, forcing the coach to call up Zambian students living in London to make up the numbers.

Football House (the FAZ headquarters) became an arena of shenanigans and buffoonery. Revenues from international matches were unaccounted for as the Zambian team made trips to play Brazil, Chile, Kuwait, Japan and other teams abroad. For the game against Brazil, sources revealed that a seven-figure sum was paid as a match fee. More telling was the absence of any entry in the FAZ books relating to the match.

Bwalya also involved himself in transfer deals for players. According to sources at Nchanga Rangers, while still a player at Correcaminos UAT, he played a part in the transfer of Harry Milanzi to the same club. To date, Nchanga Rangers hasn’t seen a cent of the transfer fee.

When Collins Mbesuma transferred from local club Roan United to Kaizer Chiefs in South Africa, Roan United found themselves holding the short end of the stick.

The biggest transfer scandal involved the movement of Emmanuel Mayuka from Kabwe Warriors to Maccabi Tel Aviv in Israel. Bwalya was subsequently summoned by the National Sports Council of Zambia to explain his role in the transfer, and was suspended for his refusal to appear. He was also severely criticised in a parliamentary report looking into the matter.

With his grip on local football cemented, Bwalya turned his attention to CAF and Fifa. He quickly ingratiated himself with the then CAF president Issa Hayatou by going door-to-door, “encouraging” delegates to make the right choice during elections. When Jordaan and current CAF president Ahmad Ahmad – both from the southern African region – stood as candidates for positions in the CAF executive committee, Bwalya took his opportunity to undermine Jordaan by fully backing and campaigning for Ahmad. He was later heard saying gleefully after Jordaan’s loss that, “as long as I am around, Danny will never get into CAF. Over my dead body.”

The big money-making opportunity came when the bidding for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups began in earnest. Qatar’s Bin Hammam and Bwalya initially became acquainted when Bwalya was appointed as an ambassador for the South African bid, and they have kept in touch over the years.

As Bin Hammam’s star grew with Qatar’s successful bid for the 2022 World Cup, he was emboldened to go for broke. His fatal error came in the final days of the campaign for the Fifa presidency. The mistake was to offer $40 000 in cash to each of the Caribbean Football Union presidents at a meeting in Trinidad and Tobago. Not all were prepared to destroy their reputations for the pieces of silver on offer, and declined to accept the cash. Chuck Blazer, the secretary-general of Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football, ever the Blatter man, and under intense pressure as a turned informer for the FBI in the US, passed on the information to Blatter, and Bin Hammam’s fate was sealed.

Bwalya’s domestic decline began in 2016 with his loss to Andrew Kamanga, a successful businessman who had previously served as chairperson of Kabwe Warriors Football Club. After the series of monumental blunders outlined above, the association’s members rallied behind Kamanga in 2011. They were thwarted at the last minute by the withdrawal of a vote of no confidence motion when the sponsor – allegedly for the price of a large television – had it taken off the agenda.

Five years later, in 2016, Kamanga made another bid for the presidency and, against overwhelming odds, defeated Bwalya by the slim margin of 163 to 156 votes. It was the biggest upset in the history of Zambian football elections. According to eyewitnesses, Bwalya, who had left the hall and returned to his hotel room before the final vote was counted, broke down and wept at the news of his loss.

After an initial inquiry into the vote-buying allegations in 2012, Fifa concluded its investigations through the adjudicatory chamber ethics committee in April. Bwalya was found guilty and sanctioned four months later. The action effectively ended his tenure at the top echelons of football.

Where he goes from here is unclear. After playing football at the highest levels and becoming a household name in the African game, his journey has careened downhill. Today, public opinion is divided over whether he is a hero or a villain.

It is yet another sad tale of how greed and corruption can eradicate a lifetime of work and achievement in an instant.

. City Press sports editor’s note: Bwalya has vowed to fight tooth and nail to clear his name

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners