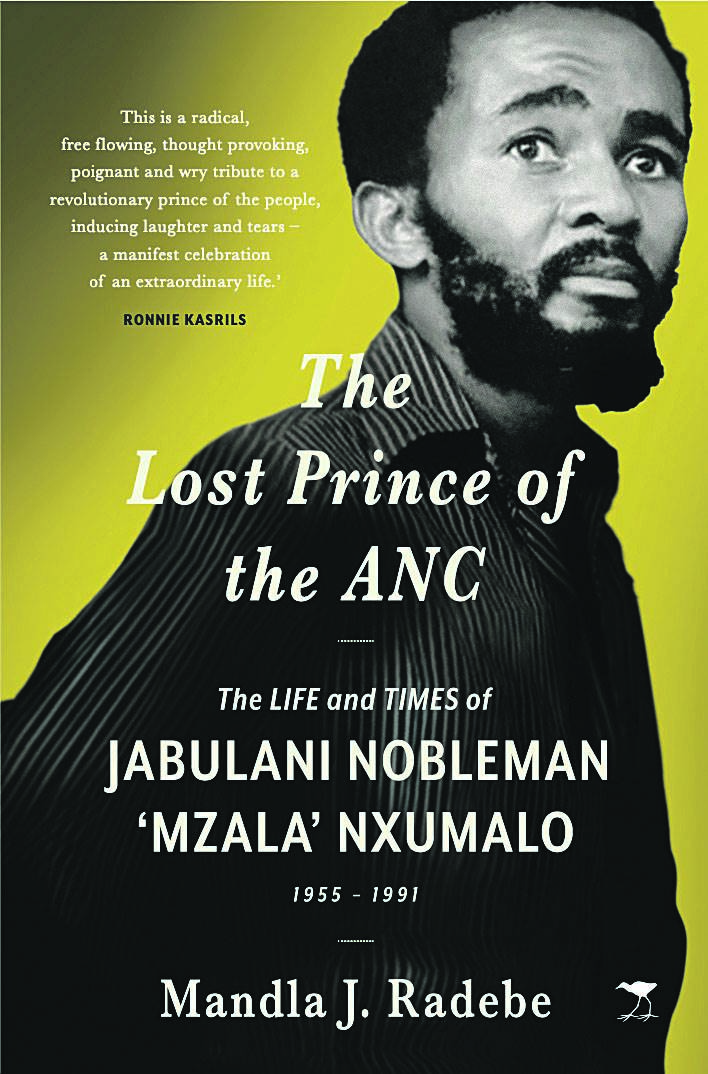

In this edited extract from his book The Lost Prince of the ANC: The Life and Times of Jabulani Nobleman ‘Mzala’ Nxumalo, author Mandla Radebe analyses some traditions within the ANC in exile, as critiqued by one of the organisation’s foremost thinkers.

Mzala continued to argue that, when new people came into exile, bringing new ideas and questions – the generation of comrades such as Thabo Mbeki, Pallo Jordan, Francis Meli and Sizakele Sigxashe – troubling challenges were suppressed in the name of “maintaining ANC traditions”. The age of the organisation was invoked as a way of reinforcing this suppression. Mzala did not see the logic to some of the so-called tradition arguments; he considered this as just a cover for unwillingness to entertain new thinking, which implied new people.

A tone of veneration was supposed to be used when speaking to the power-holders. When speaking of [Alfred] Nzo, one refers to him as “the SG” [secretary-general]. And one had to go through these people to get to Tambo, although Tambo sometimes on his own jumps over these people when he sees a situation that requires his intervention.

By the time of the post-Soweto influx, he said, the power structure in the organisation had hardened, with the ”clique” having established a modus operandi among themselves. They had “learnt how to reproduce a type of underling who was to their liking”, a “yes man” and a “choir”.

In this regard, Mzala characterised four types of the younger generation in the ANC.

READ: Editorial | This is the culture of the ANC

The first type, he said, comprised those who were noticed, chosen and promoted by the leadership because of their loyalty and unquestioning attitude. “In return for their loyalty,” he pointed out, “they are praised and built up into ‘little idols’. If they ever once begin to ask questions or show less than 100% personal loyalty, then they are unceremoniously dumped.” Mzala made an example of Welile Nhlapo (also known as Welile Mkhize), whom he described as “an outstanding youth leader in SASO [the SA Students’ Organisation] before 1976”. Because the ANC needed credible people from this group, Nhlapo was made head of the youth section.

Mzala identified the second type as a group of loyal individuals, partisan to the ANC as an organisation but critical of the leadership. In the main, he said, this is the post-1976 group that went into MK [Umkhonto weSizwe]. “Some became discontented because of stagnation in [the] camps when nothing seemed to be happening. If they expressed this discontent, they were regarded as a threat, and the favoured method of silencing them was to accuse them of being agents.” Although suspicious caution was necessary because the agent problem was real, this was also a useful method to silence dissent. Others were not accused of being spies, he posited, “but were squelched by being accused of being ‘anti-leader’, which was considered a very bad label to have pinned on you”.

In Angola, there were some people who were imprisoned by the movement for eight years and nothing was ever proven against them; when they were let out, they demanded explanations and never got any. The Angola mutiny was the clearest case of demonstrating the problem of lack of democracy in the ANC. People in this category who got too dangerous would be attacked in Sechaba, etc.

When one traces Mzala’s history in the movement through his actions and writings, it becomes clear that he belonged to this group. As a product of 1976, Mzala was not one to be silent. This was against his character. He sided with comrades who were critical of the leadership and openly punted the “people’s war” strategy. Not many comrades had the courage to tell the organisation that it was ”building pyramids in Egypt”. For this, he was one of those comrades labelled an “agent”.

READ: The ANC: An organisation at war with itself

The way he left the country did not make things easy for him. Dumisani Nduli recalls a group that tried to label Mzala a spy, using some dubious argument that he was seen carrying a phone when students torched the administrative building at the University of Zululand in 1976.

Mzala classified the third type as those who were “just there” and made no waves. At public meetings, they shouted “Viva!” and “Down with X!”, sang the national anthem – but later, in the shebeens, after they had a few beers, they complained bitingly, called leaders nasty names. In the shebeens and bars, the first type – the “blue-eyed boys” – were berated with names worse than spies and were seen as yes men by this third type. He said one of the milder epithets was “the members of the members” because, while they were members of the ANC, they could be regarded as “special” members.

Mzala characterised the fourth type as those people who had recently come out of prison. He saw them as closest to the second type: they are critical of lack of democracy. Some of them are veterans of the Angolan camps and have carried that grievance with them. In prison, there was actually more democracy and much more open discussion, in spite of the Rivonia “elders” not being all that attuned to it (with the partial exception of Sisulu).

For Mzala, none of the four types extended to cover those in the movement who had been genuine “mischief-makers”, critics who were not serious about achieving the organisation’s goal.

He used the Kabwe Conference to demonstrate his point. The Angolan delegates had organised themselves to try to sway the conference, he said. “They wanted to challenge delegates who weren’t elected but got credentials anyway ... When they tried to raise questions on how delegates had been accredited, they were met with a ‘choir’ of boos, etc, well orchestrated.” Mzala contended that, since the unbanning and the release of political prisoners, many more openly “heretical” ideas were being expressed in meetings. He thought the leadership no longer had control and thus could not silence the critics. He was simultaneously predicting and advocating that the present power-holders were “simply caretakers and that, in December, there will be quite a cataclysmic change. December won’t be anything like Morogoro and Kabwe, where things were tightly controlled.”

By “December”, Mzala was referring to the first consultative conference of the ANC to be held in the country. He was basing this prediction on the reaction after the Groote Schuur meeting, where “branches berated [secretary-general] Nzo for not consulting about what positions the ANC would take, and not reporting back afterwards”. On May 4 1990, the apartheid government and the ANC met; in what became known as the Groote Schuur Minute. An agreement was reached on a common commitment towards the resolution of violence and intimidation, commitment to stability, and a peaceful negotiation process.

READ: Mashatile in pre-conference extortion drama

According to Mzala, there were angry people at the London branch meeting when he [Nzo] came there later; they said: “We are not just journalists waiting to take down notes on what the line is now.” Earlier, when Walter Sisulu came to Lusaka [Zambia] the first time, he was bombarded with a storm of protest and complaints against the leadership about the lack of democracy.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners