During the ANC’s salad days, big business enjoyed a complex and contradictory relationship with the government. On the one hand it helped offset the party’s calcified credo of socialist economics, thus bolstering the Rainbow Nation’s democratic prospects.

But, in another sense, the accommodation that big business found with the government (and, through it, with organised labour) in statutory bodies like the National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac), served to sanction ANC hegemony.

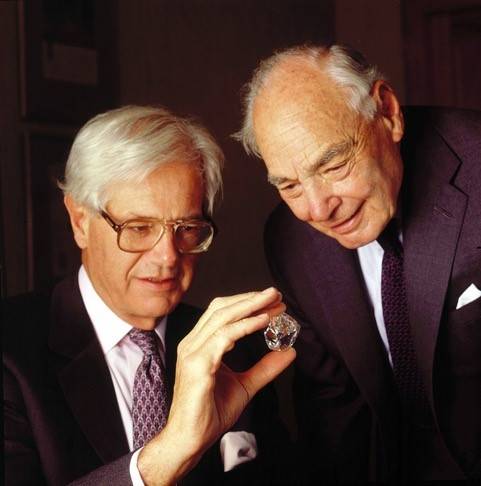

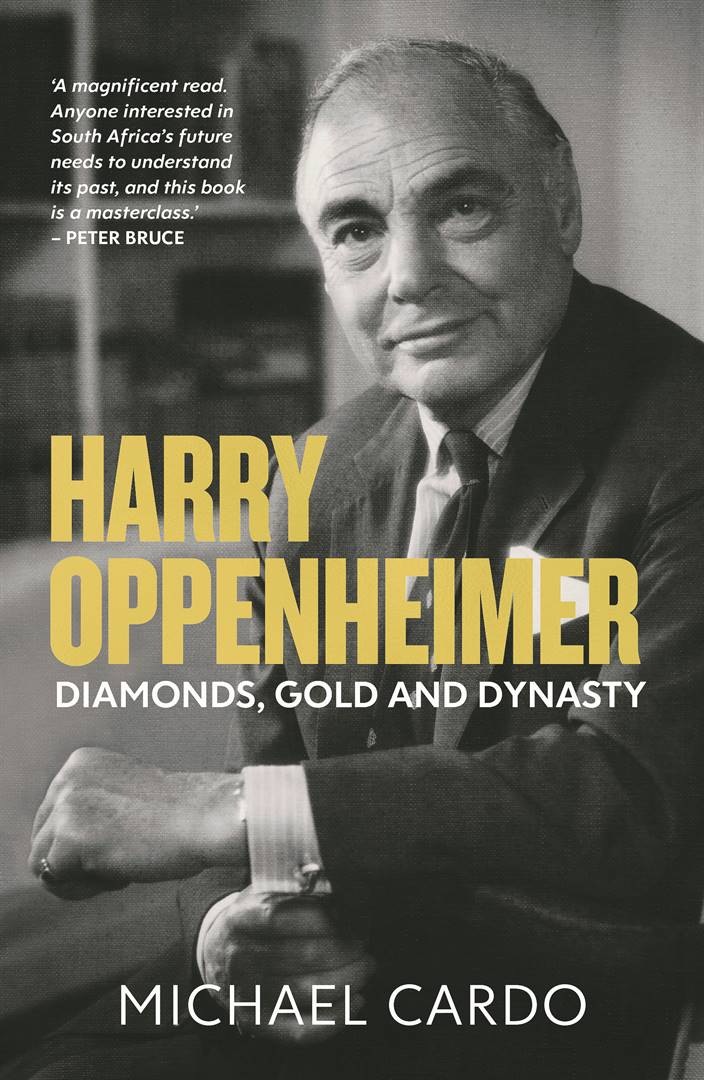

Unlike Nedlac, the Brenthurst Group, convened in the studious seclusion of Harry Oppenheimer’s Brenthurst Library, was an informal initiative which brought together senior representatives from big business with ANC movers and shakers under Nelson Mandela’s leadership. The aim was to foster dialogue, establish trust and build consensus on South Africa’s economic future.

The engagements were benignly overseen by the plutocrat and the president, rather than actively propelled by them. Nevertheless, here was the moment, its leftist detractors charged, when a coterie of powerful white capitalists and emergent black rulers, embodied by Oppenheimer and Mandela, struck a Faustian bargain. In secret, they hammered out a pact, the effect of which was to leave the structures of economic power largely undisturbed.

White business captured the ANC’s economic policy-making process; it emasculated the Macro-Economic Research Group (the SACP- and Cosatu-friendly outfit which advised the ANC), and caused the party of liberation to stray from a broadly social-democratic trajectory on to a conservative, neoliberal path.

The truth was more prosaic than such conspiracy theories permit. The ANC’s major economic shifts were occasioned by the collapse of communism and the force of global pressures, among them the fiscal and monetary prescriptions of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

READ: Mondli Makhanya | We will rue our inaction

The party’s economic repositioning predated the formation of the Brenthurst Group in 1994. In point of fact, the intermittent conclaves in the Brenthurst Library made a marginal, but not material, impact on ANC thinking.

The impetus for the Brenthurst Group came from the ANC. It was Alec Erwin, the former trade unionist soon to become Mandela’s deputy minister of finance, who contacted Bobby Godsell at the end of January 1994, at Mandela’s behest, and got the ball rolling on the get-togethers. Mandela was keen for the ANC’s economics brains trust to meet with “a group of leading businessmen”, Julian Ogilvie Thompson wrote confidentially to Donald Gordon, “to lay the foundation for a constructive pattern of relationships” with the business community after the election. The first meeting was hastily arranged and took place on February 22.

Alongside Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, the ANC fielded its key economic planners – Erwin, Trevor Manuel, Tito Mboweni – together with Franklin Sonn and a national executive committee member, Cheryl Carolus; they were flanked by a mini-federation of trade unionists, Mbhazima “Sam” Shilowa, John Gomomo and Jay Naidoo. The business attendees constituted the crème de la crème of white corporate power: HFO [Harry Oppenheimer], Clive Menell (Anglovaal), Warren Clewlow (Barlow Rand), Marinus Dalling (Sanlam), Mike Levett (Old Mutual), John Maree (Nedcor), Conrad Strauss (Standard Bank) and a slew of executives from the Anglo American stable.

“Their collective industrial power represents virtually the entire formal economy of South Africa,” gasped one journalist, two years later, after the existence of the secret synod became known.

Mandela kicked off the discussion by stressing that the ANC had an “open mind” on the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), the party’s socioeconomic policy framework drafted by Naidoo. The RDP set ambitious targets for land redistribution, housing and the provision of basic services, but it was essentially an election manifesto rather than a systematic plan. The economic section was riddled with ambiguities: it promised massive state spending while pledging to avoid undue inflation and balance of payments difficulties.

The RDP was widely disseminated and endlessly consulted upon by the Tripartite Alliance partners; international financial institutions scrutinised the document, and it was submitted for approval to the governments of Britain, America, France, Germany and Japan. By the time the RDP white paper was gazetted in November 1994 – Naidoo became the minister responsible for its implementation – it had undergone multiple revisions. The draft before the businessmen assembled in the Brenthurst Library, Mandela reassured them, was not a statist blueprint; the idea was to “empower civil society” to play an active role in delivery, and the ANC had consciously sought to avoid stressing development at the expense of growth.

“There was a guarantee of no radical policies that could damage our economy,” Anglo’s Michael Spicer underlined optimistically in his notes on Mandela’s opening remarks.

Oppenheimer spoke next. He paid personal tribute to Mandela, and affirmed that a “close understanding” between business and the ANC alliance was desirable.

There was an “urgent need to tackle poverty”, HFO concurred, but he cautioned that poverty should not be addressed in such a way as to discourage growth. Manuel then expanded on the RDP’s salient features. HFO’s approach in the inaugural meeting of what was to be the genesis of the Brenthurst Group, and in the dozen or so encounters that took place over the following two years, was decidedly hands-off. He sat back, performed a sort of ceremonial role, contributed infrequently and gnomically, and gave Strauss free rein to chair the gatherings on business’ behalf. The two sides traded courteously in generalities. It was left to Ogilvie Thompson to underscore that reconstruction and development hinged on economic growth; he suggested that the word “growth” be inserted into the title of the RDP.

“It was an almost wholly useless exercise,” Godsell later recalled of the Brenthurst colloquies, “because on both sides people were excessively polite.”

It is true that the Brenthurst businessmen proposed several amendments to the RDP to make it more investor-friendly – including a firmer commitment to fiscal discipline, deficit reduction and trade liberalisation – but those suggestions were hardly original or unique, nor did they make the critical difference.

“ANC policy evolved in a convoluted way,” Spicer recollected, “and we often struggled to understand where it was headed.”

Mandela once called a meeting to discuss the “excess number of civil servants”, many of whom, Ogilvie Thompson recounted the president bemoaning, “simply ‘play cards’”.

READ: Sustained rolling blackouts hurt job creation

Yet the first occasion on which business requested a meeting, Strauss observed at the time, was as late as July 1995, to register its concerns over the Labour Relations Bill. Up till then, the ANC had made all the running. Godsell’s minutes and Spicer’s notes provide no evidence that big business extracted significant concessions from the ANC at meetings of the Brenthurst Group. Oppenheimer, like the other businessmen present, would have hoped for a fully liberalised economy relieved from the burden of exchange controls. That was never on the table.

The labour regime which emerged out of the Labour Relations Act was rigid: it protected and benefited workers, not their employers (or, for that matter, the unemployed).

In 1996, the government more or less abandoned the RDP in favour of a macroeconomic strategy more closely aligned to the “Washington Consensus”. Initiated by Erwin and championed by Manuel, it was named Gear (Growth, Employment and Redistribution). Gear was the outcome, in one academic’s overwrought view, of “an intense ideological ‘onslaught’” and “religious crusade” by “powerful right-wing pressure groups”, who emerged as ideological conquerors in June 1996. Quite possibly the ANC’s retreat from the RDP was accelerated by the Brenthurst Group’s corporate conquistadors.

Roughly nine months before Gear’s release, some of them revived the dormant South Africa Foundation (SAF) – unlike the Brenthurst Group, the SAF was an entity which had never concealed itself from public view – and in March they presented an SAF document, Growth for All, to Mandela. It made the case for a flexible, two-tier labour market system, privatisation of state assets and export-driven growth. The ANC responded with horror. Mboweni led the attack, particularly on the SAF’s call for labour market deregulation.

READ: Private operators can generate additional revenue for Transnet

Mbeki, who ran the engine room of government while Mandela bestrode the decks as honorary captain, was publicly silent but privately infuriated. He found the Growth for All document high-handed, prescriptive and pre-emptive. He stewed over the timing of its release.

Gear, Mbeki anticipated, would be seen as a defensive response to Growth for All, and thus raise the hackles of the labour movement and the left. Ironically, at the same time that the government’s switch from the RDP to Gear drove a wedge between Mbeki, Cosatu and the SACP, Mbeki fell out with the SAF and “the Anglo crowd”. He felt alienated by their conduct and bristled at what he perceived to be racial slights. (Strauss, frustrated by his failure to nail down a slot in Mbeki’s diary, had famously vented to Mbeki’s PA: “If he cannot manage his diary, how can he manage the country?”) At that point, Mbeki effectively shut the door on any kind of special partnership with big business.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners