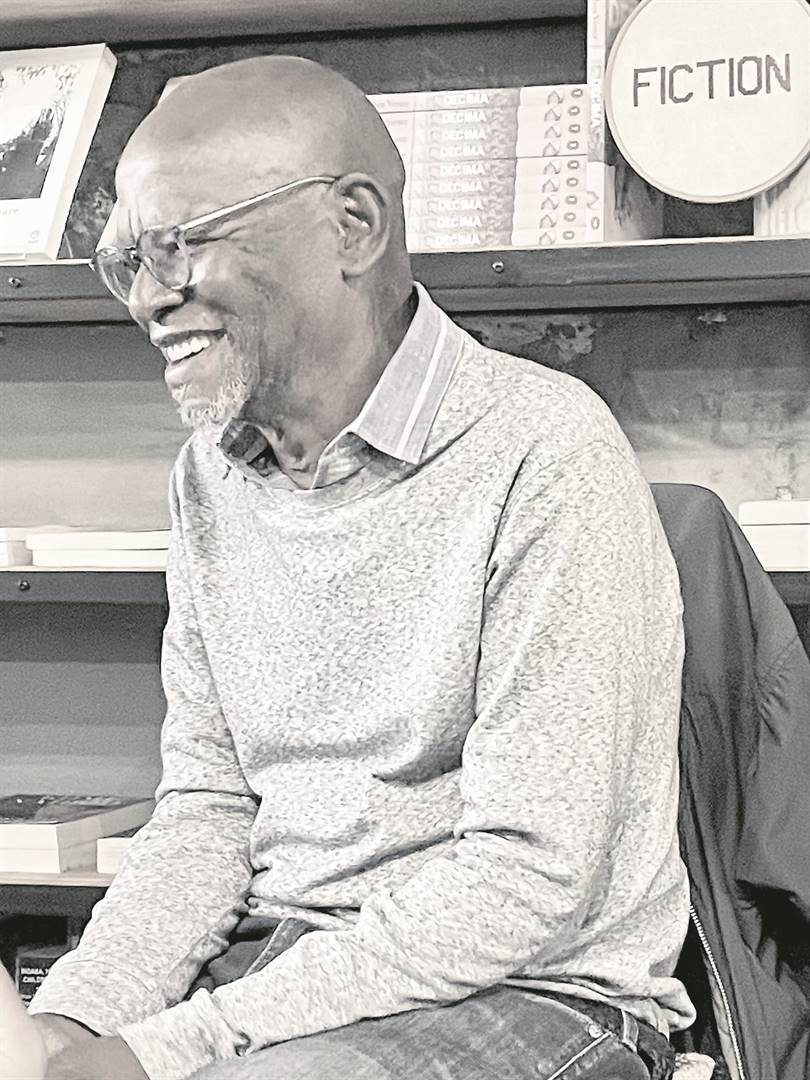

AUTHOR: Morabo Morojele

PUBLISHER: Jacana Media

When I started reading this book, it suddenly dawned on me that this was going to be only the fifth novel that I’d be reading about Lesotho.

My first literary encounter with the mountain kingdom was through Maseru, My Horse, a short novel that was prescribed for Standard 8 pupils back in the early 1980s when I was in high school.

The second one was Zakes Mda’s breathtaking She Plays with the Darkness, which I read in 1991. The third was, incidentally, Morabo Morojele’s novel How We Buried Puso, which I read in 2007. The fourth was Mda’s Wayfarers’ Hymns.

I am deliberately not mentioning Murder at Morija by Tim Couzens because it is not a novel. And now I have just finished novel number five set in the mountain kingdom.

READ: REVIEW | Zakes Mda's latest novel is a wonderfully rich tale of loss and reinvention

When I was growing up, stories about Lesotho and the Basotho people featured strongly in the folktales my grandmother used to tell us. These were tales about the cannibals who lived in caves in the mountain kingdom long ago; stories about King Moshoeshoe’s wisdom, stories about a monster called Kholumolumo.

Yet we don’t read a lot of these stories in contemporary books. Perhaps it’s my fault, maybe I haven’t been looking hard enough for books from or about that country.

By contrast, I have devoured in excess of 40 books set in Botswana – mainly by such writers as Lauri Kubuitsile and Alexander McCall Smith. One of McCall Smith’s books, The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, was even made into a movie featuring American musician Gill Scott.

I had to raise the concern about either the paucity of books from and about Lesotho, or the lack of marketing around them. While Lesotho is physically part of South Africa, the country has a distinct identity and history. This identity defines the set of challenges that Lesotho faces, as opposed to the issues that South Africa is grappling with.

And that is where Morojele’s latest novel, Three Egg Dilemma, comes in.

The importance of this book is not just that it is set in Lesotho and is authored by a Mosotho chap, but it is about what it seeks to achieve. Or what I believe it seeks to achieve.

The book is a powerful portrait of Lesotho as she is right now. No piece of journalism that I have been exposed to thus far matches the power of this book in telling the story of contemporary Lesotho.

READ: Siyabonga Hadebe | Lesotho 'land claim' is a dangerous colonial distortion

In prose that is dreamlike and so painfully beautiful, the novel tells the story of what happens to ordinary people when a country’s power-mongering elite goes to war.

The story is told in the voice of EG Mohlala, a well-travelled and well-read Mosotho intellectual who has retired from it all: from his life, from romance, from life itself. He just sits at home, drinking with some of his tenants, neighbours and ill-assorted friends.

The agony of it all flows in the streets, it seeps through the gaps under the citizens’ locked doors, through the broken windows, through the leaking roofs – to contaminate the lives of citizens who have run out of places to hide. Where do you hide when even your home is not safe?

In one instance, when the hoodlums led by a warlord called Zuluboy wreak havoc in the hitherto peaceful and relatively upper-class neighbourhood where our narrator lives, he is left with no option but to run away from his own house. He and a handful of friends take refuge in a nearby cave, until Zuluboy and his followers leave the neighbourhood.

In his adroit observations, the narrator tells of his neighbours: a group of ganja-smoking youths who believe that they are rastas, although the narrator clearly doesn’t believe these kids know what Rastafarianism is all about.

Then there is his friend Sticks, who sells boiled eggs in the streets to eke out a living. There’s the shop-owner, Mada, at whose establishment the bulk of this sad and shocking story plays itself out.

Most importantly there is Puleng (who later gets named Pearl by her employer who finds the Sotho name “difficult” to pronounce).

The narrator spends a lot of time talking about, talking to, dreaming about Puleng. He feels a lot of affection for her, but, being the conscientious person that he is, he realises that she is young enough to be his own daughter, and thus decides to curb his enthusiasm.

But there is a disturbing scene when he grabs her, and almost rapes her.

It’s a disturbing moment because, thus far, the reader likes EG. The reader is sympathetic to his travails and believes he is a good guy. And then this!

The scene speaks volumes about how the powerful can get away with murder – both figurative and literal – in times of both peace and war.

The character who completes the dramatis personae is ’Mota’s Ghost. We first encounter the ghost in the early chapters of the book when it simply enters the car that EG is travelling in with his friends.

In later chapters, the ghost keeps reappearing, gradually insinuating itself into the lives of the characters of the book and into the mind of the reader. By the end of the book, the ghost is so central to the story that it is difficult to imagine a denouement that does not feature it.

While the author clearly did not mean the book to be entertaining – it’s about war, about zama zamas, about disease, starvation, deprivation – it is surprisingly engaging. And funny.

The humour is generally dry. But there is one really light moment that some of you who have relatives who have been to prison will relate to.

The scene is about Sticks, the narrator’s “bestie”. Sticks is a shady character who is in and out of prison.

Let me quote the scene at some length:

“One of the prisoners stole it and squeezed it between his buttocks, where the prison guards would not search too eagerly upon their return. For a week or so, it was passed from cell to cell in exchange for tobacco, the prison currency. The minister must have missed it, a favourite perhaps, because one day as they were being released from their cells for their customary cold water wash, the guards ordered each of them to hold the few belongings, their clothes and their blankets and bibles in their arms at the front of their cells, and proceeded to search each one.”

You can’t help but laugh out loud at that. I also love the fact that though this is a book about fighting, most of the violence is hinted at. It is not gratuitously reproduced on the page. Yes, there are some startling violent scenes. But not many.

Oh, did I mention that Morojele, who is a jazz drummer, writes sentences that can be enjoyed just for their musicality?

I love the fact that, though this is a book about war, a sick country, a country ravaged by hopelessness and despair, a country depraved and deprived, the humanity of the characters is what stays with the reader long after the book has whispered its last sentences to them. It is a book that should remind us that Lesotho is not the tenth province of South Africa. A book that celebrates the resilience of our Basotho brothers and sisters.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners