It was known as Black Wednesday. On October 19,1977, The World and Weekend World were banned. The editor of The World, Percy Qoboza, who became the editor of City Press in 1984, was taken into detention and held for five months under section 10 of the Internal Security Act in Modderbee Prison.

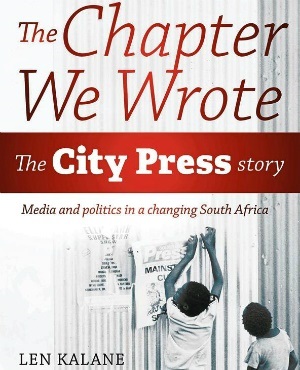

This is an extract from

Chapter eight: Inja’mnyama

Percy Qoboza was many different things to many different people.

He was, you could say, the kind of man you loved to hate, and this would not be an unreasonable surmise.

Qoboza would be your best friend today, and your worst enemy tomorrow. He really blew hot one moment, then inexplicably cold the next.

We called him Inja’mnyama, an isiZulu word meaning “the black dog”. And he liked the nickname. It was used more in deference than in a derogatory manner.

Qoboza had almost single-handedly charted a new course in black journalism – a new form of black journalism dealing with the social and political issues at hand to spur on the struggle against apartheid and injustices.

Calling him Inja’mnyama was therefore our expression of profound awe, deep respect, maybe even fondness. But this depended largely on the status of your relationship with him at any given moment.

Qoboza encouraged the Jim Bailey culture of after-hours office drinking. In our drunken stupor, as the effects of the alcohol set in, chants of “Inja’mnyama” would invariably be part of the revelry. Some of us would be thankful for his munificence, as drinks and eats – always provided out of his own pocket – were abundant whether at his house or in the office.

Qoboza, a would-be priest-turned-journalist, was, as colleague Sekola Sello once noted, not given to using subtle language. Sello wrote: “If he thought you were a piece of you-know-what, he said it in the most crude and direct isiZulu or Sesotho imaginable. This trait, I think, he picked up from his friend and mentor, the ageless Selwyn ‘Duke’ Moleko.”

He was also, as Sello described, a son of the soil. Qoboza, he wrote, relished the company of the ordinary rather than the high and mighty.

Indeed, Joe Thloloe, who worked with Qoboza for years, recalled how Qoboza would send his driver to buy iskopo (sheep’s head, also known as a “smiley”) and he would sit and eat it there, among the people. He also loved his drink, Thloloe said – neat brandy.

Thloloe said: “He loved skaap-kop – most days he would send his driver to a house opposite the Orlando Police Station to buy him his smiley.

The driver would come back with the smiley wrapped in newspapers and Percy would eat it with pap in his office.

He also loved brandy, and presided over the Litre Club – a group of journalists who met in Mofolo Village every night and consumed at least a litre of brandy.

They had a roster for who would buy it, and every so often a litre would become two litres or more.

In the morning, Percy would be bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, and was merciless with any members of the club who arrived late for work.”

By the time I got to socialise with Qoboza, he had switched to gin. I once asked him why. Pointing his finger towards the heavens, the response came with a curt “I nearly saw my mother!” Qoboza almost drew me into this heavy, dangerous drinking culture, but luckily I escaped.

The routine was the same: we would start at the office and proceed to his home or to the “Summer Residence”, where we would continue to drink late into the night. Every day.

There were good times, good discussions and good fights. He was very vindictive, we all knew that, so you had to watch your step with him.

He either liked you blindly, as he did Duke Moleko, or hated you intensely. If he considered you an enemy, he would really turn the screws on you.

Once, he interrupted his leave for a few hours to go to the office to fire one of his editorial executives, and, mission accomplished, went back home to resume his vacation.

At the receiving end of this unprecedented wrath was Leslie Sehume, the sports editor who was also a known Qoboza rival and challenger for the editor’s seat at The World newspaper.

Sehume had slipped up when word came out that he was part of the Committee for Fairness in Sport, one of the many tendrils of the Information Scandal. In Qoboza’s eyes, Sehume had sold out – the perfect excuse to get rid of him. Until his death, Qoboza relentlessly hounded and vilified Sehume. One thing was certain, Qoboza sure knew how to spray vitriol.

There is a main road cutting across Senaoane in Soweto on its way towards the old Potchefstroom Road (now Chris Hani).

Where the street assumes a gentle curve, the Qoboza house would come into view in front of you on the right – you couldn’t miss it.

The “big house” still stands, but was sold after Qoboza died. Perched on top of his postbox near the gate was a fist clenched in a black power salute with the word “justice” inscribed on it.

In his living room, just like in his office, there was a picture of American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr hanging on the wall. Next to King’s portrait was a framed copy of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Qoboza was so obsessed with the civil rights movement that he even had an audio version of King’s speech on vinyl, which, a year or two before his death, he bequeathed to me, along with a recording of Handel’s Messiah.

Barefoot and wearing just his checked Bermuda shorts, he would sit on his veranda and enjoy sundowners in the company of Duke, watching Soweto’s street life pass by.

Being dogmatic, this was his routine, weather permitting.

That’s where I found him one spring afternoon in 1983 – topless and shoeless, gin and tonic at the ready – when I parked my car next to his gate on a mission to sensitise him about the offer to come and join City Press.

This time around, however, he was alone – Duke Moleko had since passed on. Finding him all by himself was very strange, as he appeared to have had monophobia, and always preferred to have people around him. This time, I was thankful to have him to myself.

Sello said of him:

Sello is right. I personally never understood Qoboza; you could say he was an enigma for the better part of his professional life and nobody really knew nor understood him, not even his closest friends.

Joe Thloloe also described him as “a complex, multilayered personality – as most of us are”.

Stan Motjuwadi once said: “It’s dangerous to be Percy’s enemy . . . I wouldn’t like to be one. I wouldn’t like to be his friend either . . . it is even more dangerous to have him as a friend.”

Sello noted, however, that “Qoboza was direct and sledgehammer-like in his editorials and columns. His pen was understood by the learned and the not-so-learned with equal pleasure.”

Among readers of his newspapers, The World, Weekend World, Transvaal Post, Sunday Post and City Press, Qoboza was held in high esteem, Sello said.

Qoboza was an avowed critic of apartheid policies, as we all know, advocating and championing the cause of the masses and the downtrodden.

He was a hero and had a profile unrivalled among his peers.

He was legendary and larger than life.

With his pitch-dark complexion, his nickname wasn’t misplaced at all. He seemed to embrace it and to marvel at the sound of it – Inja’mnyama. The Black Dog.

Born and bred in Sophiatown, Qoboza soon relocated to Soweto after the apartheid removals. He told me that he joined up with a township mob known as the Black Swines, which had territorial battles with other gangsters.

Then there was Black Wednesday – 19 October 1977. Security police came to his offices at The World, where he was editor, and took him into detention under state security laws. The day also saw a clampdown on other political activists considered to be threats to state security, many of whom ended up languishing behind bars at Modderbee Prison in Benoni, without charge.

Seven years after Black Wednesday, when he was associate editor of City Press, Qoboza recalled the day in the City Press October 21 edition:

Seven years ago today, the government of this country went mad.

After the 1976 Soweto riots – which gradually escalated into the biggest national upheaval since Sharpeville – the government, particularly the then Justice Minister Jimmy Kruger, completely lost direction and engaged in what was probably the biggest act of political insanity this country has ever known.

With the stroke of a pen, Kruger banned 19 black organisations, two newspapers and detained more than 50 black leaders. It was a day that has come to be known as Black Wednesday.

I think it was to be expected from a government that had completely surrounded itself with the most draconian pieces of legislation the world has ever known. My own time-table was predictable. It started on Monday, October 17. At exactly 4pm, my

family was surprised by the sight of a gleaming hearse parked at my gate.

Out jumped a friend, the late K Mageza, who used to run a funeral parlour in Soweto. He had, as he explained to my stunned family, just received a phone call to come and pick up my body. According to the caller, whom Mageza identified as a white man with a heavy accent, I had just been run over by a car and died on the spot.

My family phoned the offices of The World – where, mercifully, I was found alive – and utterly depressed.

Everybody was relieved.

On the morning of October 18 came the devastating call from Prime Minister John Vorster. He warned that he was getting impatient with The World and Weekend World. His point of ire was that we were at the time running a poll in the paper in which we asked our readers to tell us whether or not they considered Dr Nthato Motlana’s Committee of Ten to be truly representative of the feelings of the people of Soweto.

The office was flooded with responses – with the vast majority voting for Dr Motlana. It was an overwhelming response which showed tremendous

support for Dr Motlana and the Committee of Ten.

Vorster wanted me to abandon the poll. I explained to him that his government had banned the Committee of Ten from holding public meetings in which the blueprint for Soweto would be discussed and approved or rejected by the people. Every meeting called by the Committee of Ten, it will be remembered, was banned by Jimmy Kruger.

I tried very hard to explain to Vorster that by running the poll we were merely gauging and giving expression to the will of the people. But it was difficult to explain anything to that man. He was a despot – intoxicated with power he enjoyed to the limit.

It’s not understandable when you come to think that Vorster and his colleagues were active supporters

and admirers of the naked racism of Nazism. He repeated what he had said earlier in one of our confrontations – that he would crush me.

That night, I was in a state of great agitation. My colleagues and I had sustained almost a year of high-powered pressure and tension – but we sacrificed. We were jailed, beaten up, shot at and literally fed on teargas – but we survived. Journalism as we had known it over the years had taken a dramatic change – for the better.

At about 2am on the 19th my telephone started ringing. I ignored it. It went on and on and in the end – to save my children from punishment of those awful sounds – I answered it. It was, according to the caller, a certain Major AJ Visser, head of the Security Police.

Many people know Major Visser.

He was one of the nastiest human beings I have ever had the displeasure of meeting. He said, in a very sneering manner, that my newspapers, The World and Weekend World, had been banned under the Internal Security Act.

“Could you ensure that no copies of the paper are on the street corners this morning?” he asked.

I told him it was humanly impossible.

He answered that it was my problem, but if just one copy of that paper was seen anywhere in Soweto, I would have a gigantic headache for disseminating a banned publication.

I told him to get lost. At 2am I am an animal, as the good major found out.

Unknown to me was that at the very same time, the major was having a ball of a time – my friends, colleagues and leaders all over the country were being hauled out of their beds and sent packing to John Vorster Square. It was a military type of operation, carried out with military precision.

At 5am, I headed for my office. I was filled with glee when I saw hundreds of bundles of The World being offloaded on the street corners of Soweto. At my offices, there was a council of war going on. The newspaper group’s executives – who had also received the sinister telephone calls – were sitting there with company lawyers devising a new plan and strategy to get the papers unbanned.

It was impossible to answer and give the many callers an interview over the phone. My secretary arranged that we give interviews at a press conference at 12.30pm that day. What we did not bargain with was that they had bugged our phones.

As national and international media people converged at The World offices for that press conference, they made their move. At precisely 12.20pm they arrived – in carloads. They arrived as if they were coming for the most dangerous criminal alive. They bundled me into a car and took me to John Vorster Square for a photograph and fingerprints.

I was then bundled into a car and taken to Modderbee Prison – which was to be my home for the next five-and-a-half months. In retrospect, I get very angry – angry that I went in that jail because they dared lie to this nation.

They did not take me to court because they knew that all the insinuations and “skinner-stories” they were telling to this nation were a pack of lies. They closed down the newspapers because they told the truth. They told the truth without fear or favour.

At the time of the ban, Kruger had in fact filed a complaint with the Press Council against us and we had informed the council that we had every intention of fighting the complaint – which was based on nothing but a vendetta to discredit us. Instead of facing us at the Press Council hearing, Kruger decided to ban the paper instead. Even where he sits in Pretoria today, he knows deep in his heart that he would never have succeeded in going through the legal processes to test his case against me and my newspapers.

The continued ban on The World and Weekend World stands today as a shameful monument to the extent to which press freedom is gagged in this country.

Qoboza and company could be detained for long periods without being charged because South Africa’s security laws allowed for indefinite detention without trial at the time.

Banning orders and other forms of prohibition on individual civil liberties were the order of the day and meted out against those perceived to be enemies of the apartheid state.

Fellow journalists also taken to Modderbee at the time included Aggrey Klaaste, Willie Bokala, Godwin Mohlomi, Moffat Zungu, ZB Molefe and Duma ka Ndlovu. Joe Thloloe, Peter Magubane, Mike Mzileni and Gabu Tugwana joined them later. Many, including Mathatha Tsedu, Thloloe and Don Mattera, were banned upon their release.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners