VOICES

In a speech last year, FW de Klerk lamented the fact that he had never been fully credited for the apologies that he made on previous occasions.

Nkosinathi Biko, the CEO of the Biko Foundation, wrote a response to this. As we reflect on De Klerk’s role in South African politics, we republish Biko’s response, which appeared in City Press on February 24 2020.

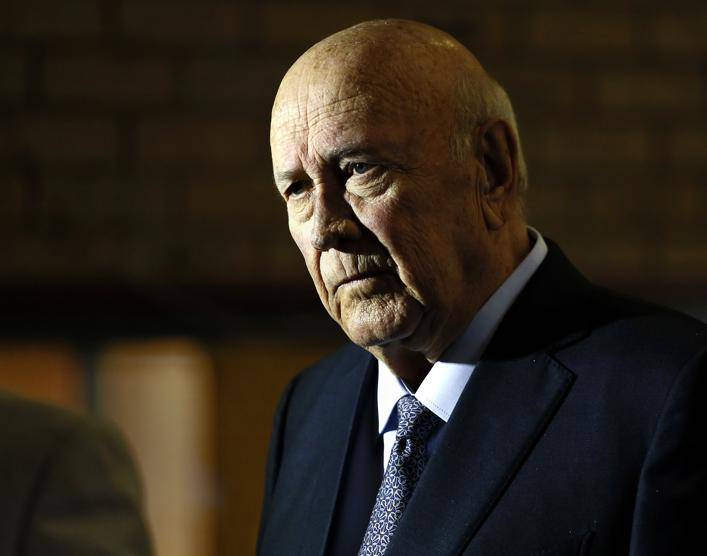

South Africans who are still nursing the raw wounds of apartheid found the recent utterances by the last president of apartheid South Africa, FW de Klerk, vile, provocative and reactionary.

The remarks were made in an interview with the SABC to commemorate the 30th anniversary of his historic state of the nation address (Sona) of February 2 1990, which heralded the unbanning of liberation movements as well as the release of political prisoners.

In the interview, De Klerk opined that apartheid was “wrong”, “had hurt people” and “was morally unjustifiable”.

READ: De Klerk dies

He then lamented the fact that he had never been fully credited for the apologies that he made on previous occasions.

Then his indignation boiled over: “But there is a difference between calling something a crime. Like genocide is a crime. Apartheid cannot be, for instance, compared with genocide. There was never genocide.”

A day later, the FW de Klerk Foundation weighed in with a convoluted statement akin to those of the Broederbond, arguing that “the idea that apartheid was a crime against humanity was and remains an agitprop project initiated by the Soviets and ANC/SA Communist Party allies to stigmatise white South Africans by associating them with genuine crimes against humanity, which have generally included totalitarian repression and the slaughter of millions of people”.

Grating as these utterances are on one’s every sense, they should not come as a surprise.

The abuse of our hard-won democracy in the name of freedom of speech is common among bigots.

In this instance, we have been gifted with an opportune window to the soul of a man whose proper place in history may be substantially lower that the sum total of his actions.

The recent anniversary of De Klerk’s speech coincided with the reopening of the inquest into the death of Dr Neil Aggett.

READ: Modidima Mannya | Zille and De Klerk are two sides of the same coin

I, like many others, attended the hearings on a few occasions, out of interest in the process of justice, but mostly because our humanity is conjoined.

As with similar incidents, which include the murder of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol, the pain of Aggett’s sister (Jill) and nephew (Stephen) should be our collective pain, given that Aggett fought for our freedom.

The history

To truly appreciate what brought us here we have to turn a few pages backwards.

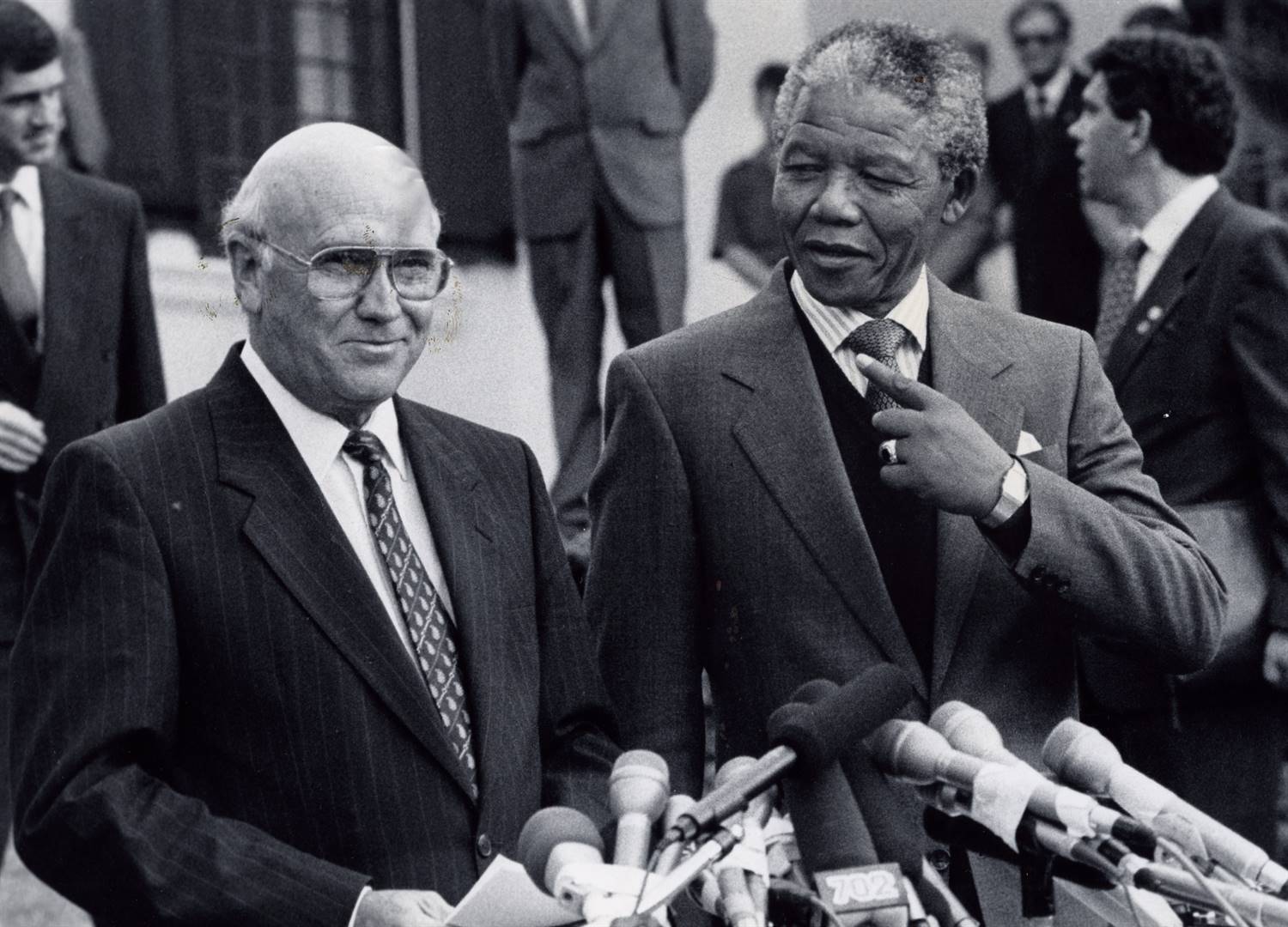

From 1990, former president Nelson Mandela took flak from the political left for daring to share a table with De Klerk and his ilk, and for leading the country to a negotiated political settlement on the terms and conditions he agreed to.

It is common knowledge that on December 20 1991, after requesting that Madiba allow him to be the last speaker, De Klerk addressed the nation at the Convention for a Democratic SA.

He used this privilege to launch an attack on the ANC, accusing it of failing to meet its commitment to abandon the armed struggle and to disband uMkhonto weSizwe.

At the end of what he must have thought would be a one-way tirade, Madiba rose from his seat to take the podium again, this time for an unscheduled response.

The disgust on his face and in his voice was palpable.

In his reply, Madiba admonished De Klerk, saying: “I am gravely concerned about the behaviour of Mr De Klerk. He has launched an attack on the ANC and, in doing so, has been less than frank.

“Even the head of an illegal, discredited, minority government, as his, has certain moral standards to uphold. He has no excuse, because he is a representative of a discredited regime, not to uphold moral standards.

“… If a man can come to a conference of this nature and play the type of politics which are contained in his paper, very few people would like to deal with such a man … I have tried very hard in discussions with him, [to show him] that, firstly, his weakness is to look at matters from the point of view of the National Party and the White minority in this country, not from the point of view of the population of South Africa.

“… I am prepared to work with him in spite of all his mistakes. And I am prepared to make allowances because he is a product of apartheid.

“Although he wants these democratic changes, he has sometimes very little idea what democracy means ... He can’t talk to us in that manner … This type of thing, of trying to take advantage of the cooperation which we are giving him willingly, is something [that is] extremely dangerous and I hope this is the last time he will do so.”

Apartheid is a crime against humanity

I was reminded of this admonition after hearing former president Thabo Mbeki comment on a brief exchange he had with De Klerk at the Sona last Thursday, wherein the latter had argued that he was not aware of the 1973 International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid.

Mbeki was statesmanly about it.

If true, a defence based on ignorance about a critical UN convention that was previously imposed on a system he later led would, on its own, be a worrisome lapse particularly for a Nobel peace prize laureate who attempted to cure the very ills of the system to which the convention relates.

It would be tantamount to De Klerk confessing that he does not know why he was awarded the prize.

But it is when taken together with the statement by his foundation that there appears to be much more that undergirds this matter than just a mere a lapse in memory.

It is apparent from Madiba’s observations of De Klerk that he is scant on goodwill and hesitant on democracy.

It is curious that De Klerk and his foundation have now positioned themselves as custodians of democracy and constitutionalism.

Madiba observed then what is clear now, that De Klerk is wont to embracing a narrow view of the world, at the centre of which is the preservation of whiteness.

But, despite his reservations, Madiba elevated De Klerk’s hand to jointly accept the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway in December 1993, and again to rehabilitate him by choosing him as one of his two deputies in 1994.

By so doing Madiba may unwittingly have unleashed unto us the best and the worst of a true “product of apartheid”.

Some have argued that at this point the liberation movement renounced the righteousness of its cause.

It had effectively created a path around inconvenient but necessary truths, equating the sins of apartheid with the response to the sins of apartheid.

It gave a pass even to the unrepentant.

The current generation of student activists who describe themselves as fallists have been scathing in this regard.

The right answer

What then is a more appropriate response to the De Klerk saga and the emboldened voice of conservatism?

We must revert to fact.

Each year between 1952 and 1990 the UN condemned apartheid as a violation of its protocols, using articles 55 and 56.

It is reported that the UN General Assembly dubbed apartheid a crime against humanity through resolution 2202 as of 1966, which was later endorsed by the Security Council in 1984.

But in between it was the Apartheid Convention of 1973, which consolidated the furthest reaching denunciation of apartheid.

The Apartheid Convention also provided for criminal action against offenders, including for acts committed on or against foreign territories such as Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Lesotho and Swaziland, if such actions were in furtherance of apartheid.

De Klerk knows of activities of the apartheid regime that qualify for prosecution under this provision.

He expects us to believe that he, a lawyer, entered into political negotiations, including on the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, without grasping his worst-case scenario under the Apartheid Convention.

It must, therefore, be by sheer happenstance that the former undercut the latter.

Despite what De Klerk refuses to remember, or how his foundation chooses to remember, apartheid was a crime against humanity.

Given that De Klerk has used up the last of his many free passes, we must not equivocate.

The apartheid state established organisations, institutions and a network of supporters through a predominantly white electoral system, which, apparatuses combined, promoted the commitment of a crime against humanity.

For a significant part of his political career, De Klerk was no mere appendage to the apartheid system.

He was at the helm of the commission of a crime against humanity.

Madiba was more than kind in describing him merely as “a product of apartheid”.

Even ubuntu has a deadline. The UN convention requires us to be more candid.

Criminal-in-chief of apartheid

Whereas some of his senior roles render De Klerk somewhere on the scale between culpable and liable, what is recorded in blood is that for the period he was the state president of apartheid South Africa, from 1989 to the first democratic elections in 1994, De Klerk, by virtue of being the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, was the criminal-in-chief of apartheid.

He was personally responsible for some serious atrocities.

This should be the start of the debate on the legacy of De Klerk, and not whether or not apartheid was a crime against humanity.

That debate, and its facts, was settled 47 years ago.

Thanks to Mbeki, De Klerk has come to discover this ancient fact, sadly long after Madiba warned him to “never again”.

Madiba invested enormous political capital on the question of national reconciliation by betting on, if not batting for, De Klerk.

Last week De Klerk betrayed that investment yet again.

But how I wish that after the drama National Assembly Speaker Thandi Modise could have pronounced on the despicable nature of De Klerk’s utterances before refocusing the House on the agenda of the day and the rules of attendance.

This test was about more than just the rules.

As I watched Sona, I wondered which of the parliamentary cultures was more agreeable for us, given the balance of our challenges.

The world recently witnessed extreme clumsiness on the Brexit issue as it was before the British Parliament.

Then there was the moral impoverishment of the impeachment of US President Donald Trump as the process went through the US Senate.

Is it the archaic stiff upper lip and grey suit culture of De Klerk’s Parliament or is it the colourful, jovial and somewhat tumultuous theatrics of our present that should define us?

Decorum has never looked out of place in Parliament. It is perhaps not so much the aesthetics, but the tenets that matter.

Our Parliament must bemoan the deferral of our people’s dream.

It must never convene for the purpose of making and of enforcing a crime against humanity, against our people or any other peoples of the world.

And if any representative should ever be so be inclined, one continues to trust that someone in our Parliament will make it their duty to out them, even if it takes a song and a dance.

Biko is chief executive of the Steve Biko Foundation. The full version of this article is available at http://www.sbf.org.za/home/category/press-statements/

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners