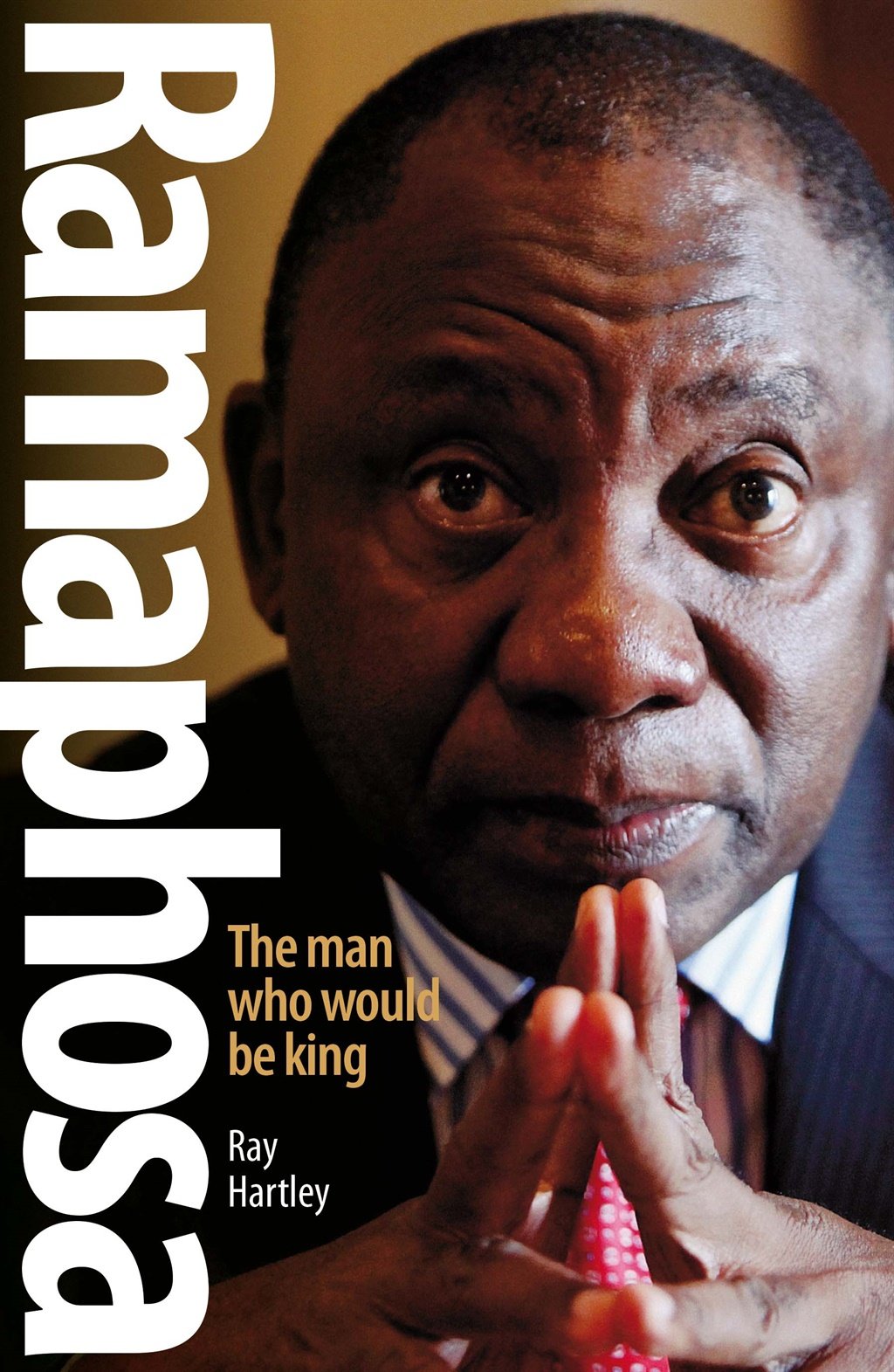

Ramaphosa: The man who would be king

Jonathan Ball Publishers

222 pages

R240

One of the keys to the success of the talks was the relationship that developed between Ramaphosa and his National Party counterpart, Roelf Meyer. Meyer was one of the party’s promising young leaders from its verligte, or enlightened, wing. He had encountered Ramaphosa before. As a deputy Law and Order minister, he had been the point man for the state during the 1987 mineworkers’ strike. It is fair to say that the relationship had not exactly blossomed, as Ramaphosa had been adamant that the state had initiated violence against striking miners or else ignored it when it was perpetrated by the mine owners.

The circumstances had changed by the time they encountered one another again. In 1992, after just nine months as Defence minister, Meyer was transferred to the portfolio of Constitutional Development, which involved him more closely in the talks between the government and the ANC. Meanwhile, Ramaphosa had systematically demolished the man who sat opposite him at the negotiations on the proposed Bill of Rights. Tertius Delport, the Deputy Minister of Constitutional Development, had been thrust into the limelight when the NP’s previous chief negotiator, Gerrit Viljoen, had taken ill and retired from public life.

I saw Delport’s demolition first-hand, as I was the minutes secretary of this working group at Codesa. Ramaphosa had a habit of never addressing Delport directly. Instead, after driving him into a state of agitation by refusing to agree to anything he proposed, he would say: ‘Mr Chairman, Dr Delport is becoming very emotional. I would appeal to you, Mr Chairman, to ask Dr Delport to control his emotions.’ It was too much for Delport and, when the negotiations advanced to the next phase, Meyer replaced him as the NP’s leading man.

Meyer readily concedes that he was at a disadvantage to Ramaphosa in the talks: ‘He came with a lot of experience at that stage already, and built up his NUM experience when he was Secretary General of the National Union of Mineworkers for quite a long period of time during the 1980s,’ he said in an interview many years later. ‘So he had an advantage at the time that we started the constitutional discussions and negotiations.’

Ramaphosa knew instinctively that Meyer was a negotiating partner he could trust. To Meyer, he was a ‘reasonable person, very reasonable in terms of understanding where the other side is coming from’. An encounter between the two while trout fishing helped forge the trust.

The incident was recorded by the late Allister Sparks: ‘A friend invites the ANC’s chief negotiator Cyril Ramaphosa and his opposite number Roelf Meyer fishing. When Meyer embeds a trout hook in his hand, Ramaphosa is the only one who can extract it.’ That moment, when Ramaphosa fed Meyer a stiff whisky before removing the hook, was but one of many that built the relationship into a political game-changer.

According to Meyer, ‘[t]hat fishing incident was just one of many, but it was indicative of the kind of relationship that we succeeded in building, the friendship that we have succeeded finally to build, and the chemistry that exists between us’. But if Meyer saw a genuine friendship developing, Ramaphosa saw opportunity. His comments on trout fishing could just as well be a description of how he evaluated negotiation opponents: ‘You need to know what they are feeding on and how they are behaving, then decide on a strategy.’

Years later, he would tell Lesley Cowling, then writing for the Mail & Guardian, that ‘the only contribution trout fishing made to the negotiations was that he learnt how his opposite number looked when he was anxious and in pain’. The trout fishing raised eyebrows within the ANC, where it was viewed as a bourgeois indulgence, but Ramaphosa had Mandela’s permission to take up the sport. ‘Trout fishing teaches you patience and to accept failure, because you can go out there and not catch anything. It’s an important attribute in life – you may not always get what you want and trout fishing teaches you that’, he told Cowling.

When it came to the negotiations with Meyer, however, Ramaphosa got most of what he and the ANC wanted: a unitary state with a government of national unity for a limited term and a constitution that would relegate the NP to oblivion and allow parties of the non-racial centre, such as the ANC, to dominate.

Once Ramaphosa had established that Meyer was not going to support a dilution of democracy with the NP’s old ‘group rights’ message, he was prepared to deal with him. The moment when this occurred appears to have been when Meyer presented Ramaphosa with a draft paper by Francois Venter, an academic influential in Broederbond, and therefore NP, circles. Venter’s paper departed from the long-held NP view that group rights should somehow enjoy institutional protection: ‘Where such a process was legally institutionalised, however, as in South Africa, the natural process of group formation took on the characteristics of external and unacceptable force.’ According to Meyer, ‘Cyril’s eyes lit up’ when he read the paper. After that, ‘it was plain sailing’.

Ramaphosa’s relationship was Meyer served a practical purpose too. When the Codesa talks broke down after the Boipatong massacre in June 1992, it seemed that the constitutional negotiations might grind to a halt altogether. Four days after the massacre, Nelson Mandela addressed a large crowd in Evaton, saying that ‘the negotiation process is completely in tatters’. He told them: ‘I instructed Ramaphosa that he and his delegation will not have any further discussions with the regime.’

Ramaphosa himself issued a harshly worded statement on the government’s violent duplicity: ‘It pursues a strategy which embraces negotiations, together with systematic covert actions, including murder, involving its security forces and surrogates.’ He presented a long list of demands, including the creation of a representative constituent assembly to finalise the constitution. Until the government complied, ‘the ANC has no option but to break off bilateral and Codesa negotiations’.

Early in September, Ramaphosa was present when troops of the Ciskei homeland opened fire on demonstrators, killing 29. The decision to mount the protest was another of Ramaphosa’s ploys to demonstrate the ANC’s ability to mobilise in order to give him an advantage in the talks, when they resumed. After the shooting, the country was at a crisis point.

The public statements made by Ramaphosa and Mandela about all talks being off were a political white lie. While formal talks in the public spotlight had been called off, behind the scenes Ramaphosa and Meyer remained in close contact. Ramaphosa was at Mandela’s side when the latter announced the suspension of talks. Minutes later, Meyer’s phone rang. It was Ramaphosa, keeping the channel between the two parties open.

* This extract was taken from Ramaphosa: the man who would be kind, by Ray Hartley, published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners