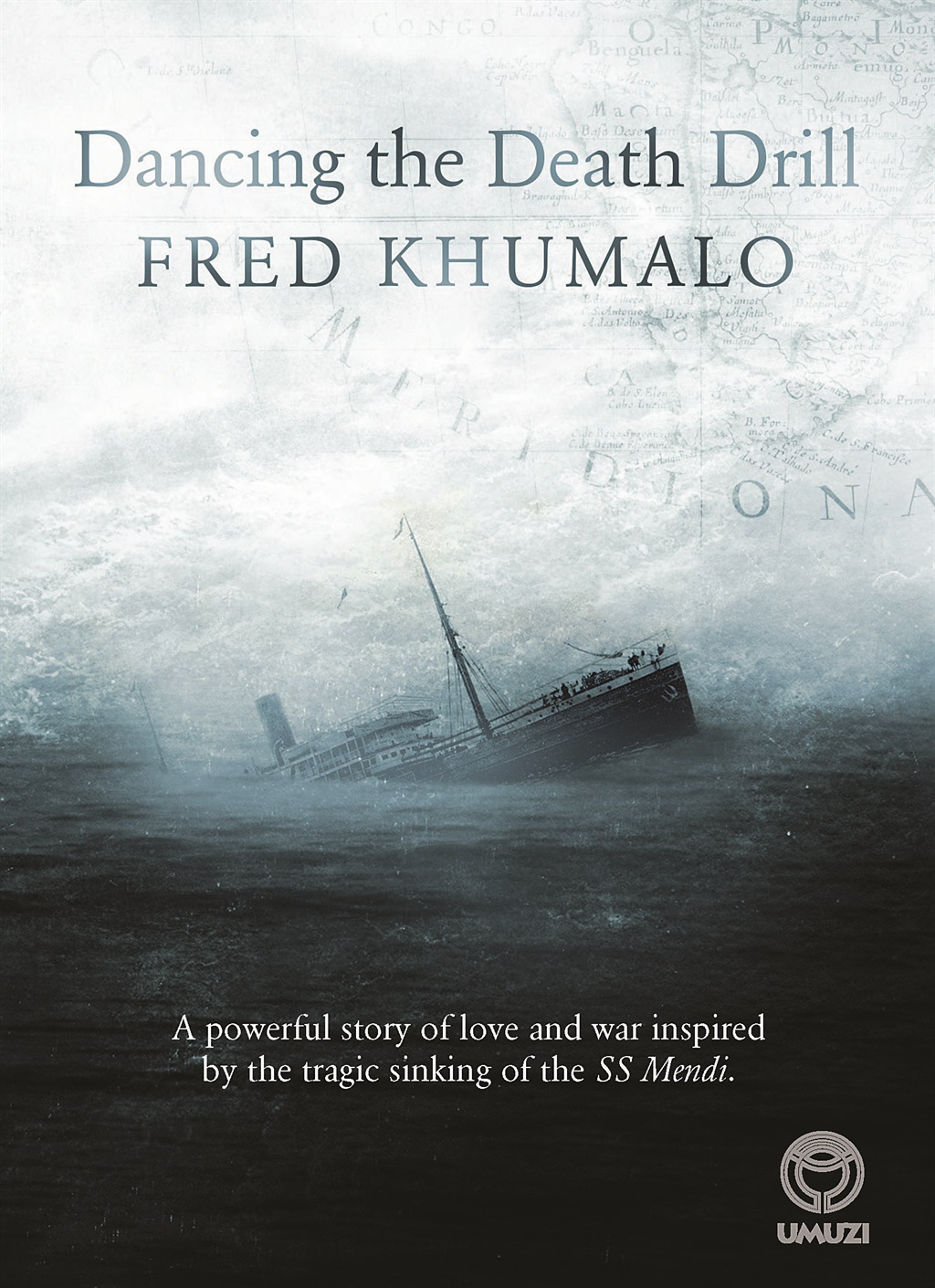

Dancing the Death Drill by Fred Khumalo

Published by Umuzi in South Africa and Jacaranda Books in theUK

R230

History is, to paraphrase the Indian novelist Arundhati Roy, like an old house at night – with all the lamps lit. The ancestors are whispering inside. But in order to understand history, we need to get inside the mansion, listen to what the ancestors are saying. Look at the books and the pictures on the wall. And smell the smells.

But what if, I ask, the doorkeeper won’t let us in? What if, when we are finally let in, our own ancestors are not, by some immutable law, a part of the whispering, part of the conversation? They are not even allowed to sit at table, let alone contribute to the whispering? Robbed of speech, they are wraiths skulking in the shadows, at the beck and call of the “chosen ancestors” who sit at table whispering about history, or, indeed, defining what history is. What then?

These are the inevitable questions that arose to me when I set out to write a book regarding an obscure little piece of South African history. A story which the chosen ancestors did not want to be spoken about in the mansion of history. This is the story about the sinking of the SS Mendi.

But what, you ask, is this SS Mendi? They didn’t tell you this in your history class at school, so let me fill that gap: World War One broke out in 1914. By 1916 it had reached a stalemate. Germany’s ambitious offensive of 1914 had overrun Belgium and run deep into France. But it had been neutralised by the Allies in Flanders, and on the Marne. German trenches and fortifications and outposts ran some 450 miles from the coast of Belgium to the borders of Switzerland.

Combined French and British responses to the German onslaught melted like snowflakes under a strong sun. The Allies were desperate for more manpower. Thus the Imperial Government sent out a clarion call to its subjects in all colonies. It should serve the reader well to remember that this country now called the Republic of South Africa did not exist then. We were still the Union of South Africa, subjects of the king.

When the call reached these shores, many black men stood up and said they were ready to serve. But white South Africans suddenly complained that arming blacks to fight against whites – under whatever circumstances – was repugnant and would set a bad precedent. There was a growing fear that this would break down what was then called the “colour bar”, and thus embolden the black man to demand true equality with the white man in South Africa once the war was over. A thought too ghastly to contemplate.

It was then agreed that the blacks would not be armed. They would be part of a labour contingent supplying services such as: wood-collecting, water-carrying, laundry, loading and cleaning of mechanical transport, camp sanitation and cleaning. Thus was the South African Native Labour Contingent born. Altogether, the contingent recruited 20 000 black men. That’s right; that figure is correct.

Now, our story concerns itself with the Fifth Battalion of this newly formed Labour Contingent. The battalion set sail from Cape Town on January 16 1917, on a ship called the SS Mendi. The ship travelled uneventfully until it reached Plymouth in Britain on 20 February. The ship offloaded some valuable goods in Britain, then embarked on the last leg of its journey, destined for France. There were 823 men on board. In the early hours of February 21, off the coast of the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, the SS Mendi was struck and cut almost in half by the SS Darro, an empty meat ship on its way to Argentina. Six-hundred-and-sixteen South African men (607 of them black troops) plus 30 British crew members perished.

The men on the ship came from a wide range of social backgrounds – some of them peasants, yet others educated men who included in their ranks traditional chiefs and men of the cloth. Many of them died on impact, while others were trapped below decks. Some of them, however, clung to the listing deck of their ship and were later saved by lifeboats from HMS Brisk, which had been sailing in convoy with the Mendi.

According to oral history, as the ship was sinking, their chaplain, Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha, ordered them to stand in formation as they had been taught on joining the army. He raised his arms aloft and cried out in a loud voice:

“Be quiet and calm, my countrymen. What is happening now is what you came to do ... you are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers … Swazis, Pondos, Basotho, so let us die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal. Our voices are left with our bodies.”

And so the men stamped their feet on the floor as they twisted and gyrated in a macabre death dance as was christened by oral historians.

It was this moment in particular that inspired me to want to revisit this story, to celebrate the valour of these unsung heroes. Research for the novel included reading Norman Clothier’s very useful Black Valour: The South African Native Labour Contingent, the only book, as far as I have been able to ascertain, that focuses entirely on the labour contingent. In addition to reading Clothier, I also visited the war graves in France. Using poetic licence, in this novel of mine, I probe the question of motive: why would black men, out of their own volition, go and fight in a war that was not theirs?

My new novel Dancing the Death Drill tells the story from the perspective of one of the survivors. Though the main protagonist is a fictional creation, in real life there were indeed survivors, as we have seen. The book tracks the life of the protagonist who, after the war, stays on in France and gets married to a French woman.

The book does not pretend to be a straight-ahead historical text. I use the Mendi as a springboard from which I launch a conversation on the subject of black men serving in wars that were not theirs. Artistic expression begins when we ask questions; when we scratch the surface; when we pull down the façade and find human beings behind it. When we insist on engaging Roy’s ancestors in debate, thus ensuring that the men of the Mendi are not reduced to numbers, to statistics; that their humanity is celebrated. That is the work of the artist as an activist.

I grew up at a time when the black South African writer faced the cruel dilemma of whether he should write or fight against apartheid, or do both equally. The poet Arthur Nortje tried to clarify the problem:

“…for some of us must storm the castles some define the happening...”

While the book challenges the orthodoxy on many fronts, it also seeks to celebrate the ordinariness of these extraordinary men of the SS Mendi. I wanted the book to be an evocation of life before and after World War One.

During my visit to the war graves in France, I was amazed and saddened that, even in death, the South African soldiers who served in France were racially segregated: the white soldiers are buried in one part of town, while their black compatriots have been allocated space at another location some 10km away.

As we commemorate the centenary of the sinking of the SS Mendi, it is only proper that we pick up this story and use it as a candle that lights the table around which all our ancestors are gathered, inside the all-inclusive mansion called history. Let us talk about who we are, where we’ve been, where we want to go.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners