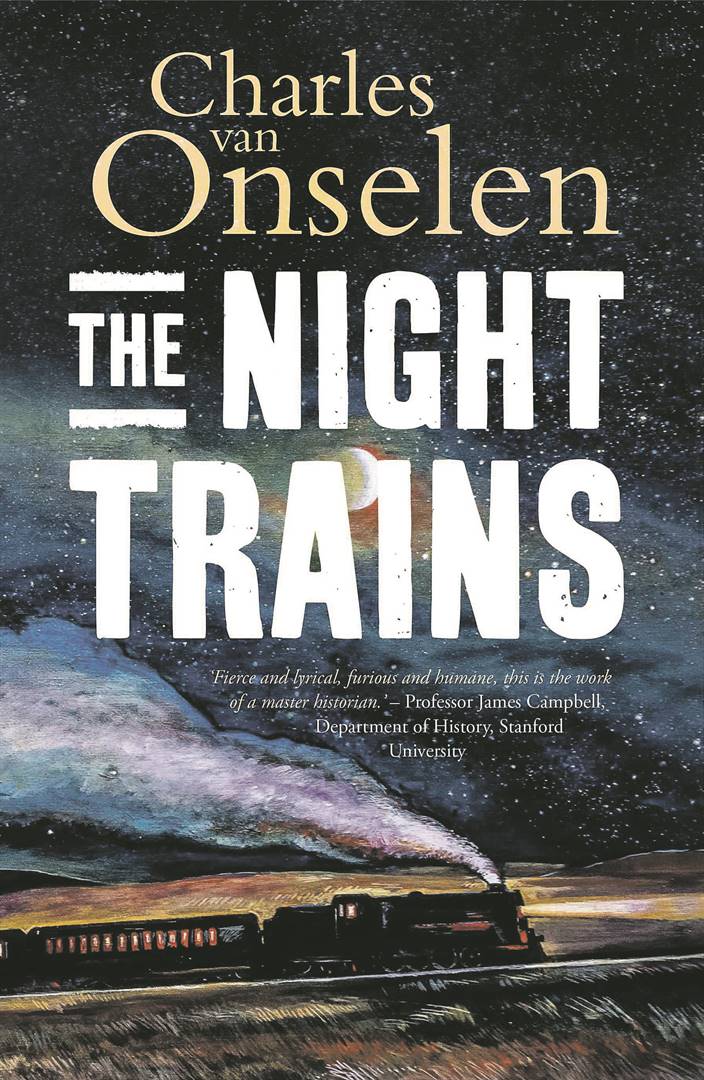

The Night Trains: Moving Mozambican Miners to and from the Witwatersrand Mines, 1902–1955 by Charles van Onselen

Jonathan Ball Publishers

256 pages

R260

A new book by celebrated social historian Charles van Onselen explores the human cost on the Mozambicans who came to work on the mines of the Witwatersrand. This extract explores the link between the mines and alcoholism.

In South Africa, as elsewhere in the developed world during the first half of the 20th century, the gold mines were characterised by assaults on mind and body alike, with consequences capable of flowing in both directions. In the US and the UK, medical science was slow to come to terms with the ways in which abnormal psychological stresses encountered in the collieries in Scotland or the US might impact on the health of mineworkers.

On the Witwatersrand, it would appear that the only people who were slower to recognise the importance of the links between the mental health of black migrants and their physical well-being were the doctors at the time and, later, medical historians. These links are only now beginning to be explored, but much more research needs to be done before we can come to a more precise understanding of the experience of black Mozambicans on the gold mines.

Until we have more professional studies, many of the stresses arising from accidents and deaths will have to be inferred indirectly from the behaviour of the migrant miners.

Throughout history, new mining towns – where men often outnumber women – have been associated with masculine excess and the release of pent-up tension through aggressive behaviour, fighting, heavy drinking, compulsive gambling or the purchase of sexual services.

Over time, such frontier-like indulgence tends to recede, if not disappear, as the composition of towns in terms of age, gender and sex ratios comes to assume a more familiar social profile.

On the Witwatersrand, however, the mining industry’s insistence on the compound system as an instrument for the control of most black migrant workers ensured the perpetuation of a family deprived, high stress and frequently loveless environment for half a century.

There was no “normal” industrialisation in what was an abnormal society.

The three-way link between South African mines, the Sul do Save – district of Mozambique – and excessive alcohol consumption dates back to the discovery of diamonds in the late 1860s.

The Thonga were among the first long-distance migrants to seek work on the Kimberley mines, and back in Mozambique, Indian storekeepers and Portuguese colonists were quick to note an uptick in disposable cash income in Lourenço Marques and the rural hinterland.

In metropolitan Portugal, the news came as a godsend for a country that lacked a broad-based manufacturing sector and struggled to sell its wine surplus in increasingly competitive and discerning European capitals. The already rapidly developing market in southern Mozambique positively boomed once gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand in the mid-1880s.

Between 1889 and 1898, wine imported into Angola from Portugal increased by 17%, but over the same period the amount of Vinho Para O Preto, “Wine for Blacks”, imported into Mozambique – with the overwhelming bulk of it adulterated and destined for the Sul do Save – increased by a whopping 1 123%. A growing dependence on alcohol and outright alcoholism became an increasingly prominent and depressing part of black social life on the mines and in southern Mozambique from the 1870s onwards and, in the latter case, remained a prominent feature until well into the early 1920s.

Predictably, an increased physiological need for alcohol – as opposed to developing a consumer centred taste for wine – eventually translated itself into a preference for spirits.

For the men of the Sul do Save, a marked shift in taste towards strong spirits in the early to mid-1890s coincided with a move from labouring on outcrop mines to working at far greater depths in the more dangerous and stressful deep-level mines. The mine owners, sensing a chance to recoup some of what was being spent on black wages and an opportunity for improving the skills and productivity levels of the workers by reducing their personal savings and prolonging the time that migrants spent on the Rand, initially opposed prohibition and invested heavily in a local distillery – Eerste Fabrieken – supplied with fruit and grain by the otherwise God-fearing Boer farmers.

By 1895, there were seven other distilling companies operating along the border around Ressano Garcia. The idea behind the unrestricted sale of alcohol to off duty black miners, however, had a few inherently contradictory outcomes, and the logic behind the scheme unravelled when large-scale drunkenness led to a reduction in the size of the pool of sober and productive black workers available to the industry on any one day.

The official estimate was that 15% of the workforce was incapacitated at any time, but unofficial estimates put the figure as high as 25% – one in four – a number that tallies, more or less, with the number of increasingly opium-addicted, incapacitated Chinese miners who worked on the same mines between 1902 and 1910.

The history of the first 20 years of the Rand mines – arguably the most dangerous decades ever experienced in the industry in terms of death rates – was characterised by foreign workforces that were significantly drug addicted.

It was, and remains, almost impossible to uncouple minds from bodies in the industry.

As the mine owners came to realise during the 1890s, any gains to be made indirectly, via shares in the distillery in Pretoria, from the sale of alcohol to the numerically predominant migrants from the Sul do Save were outweighed by what was lost through the loss of a sober and productive workforce. So they became champions of prohibition, which duly became the law in 1896. This was followed, in 1900, by a ban on the production and distillation of spirits within Mozambique itself, but not on the sale of wine.

For the better part of 30 years, from around 1890 up to about 1920, with the odd interruption such as that occasioned by the Anglo-Boer War, the Chamber of Mines, mine managers and the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA) agents helped sustain, and unashamedly made use of, the pernicious primary link that the Portuguese had forged between alcohol, the Sul do Save and black miners on the Witwatersrand to control the mine owners’ favoured pool of cheap and captive labour in southern Mozambique.

When the production of cheap spirits destined for the African market was progressively dismantled on both sides of the border, between 1896 and 1902, the Chamber of Mines, reluctant to forego the link entirely, persisted with a low alcohol “kaffir beer” ration in mine compounds.

As late as 1917, the WNLA agents were still making use of dance and wine parties in remote Sul do Save camps to groom potential recruits, and until at least the World War 2 seriously or terminally ill migrants on the 307 down train were provided with brandy to ease their pain – a concession never granted legally to other black workers.

In several respects, then, when it came to the well-being of black industrial workers, as opposed to that of white miners, the mining industry in South Africa and Mozambique was either beyond the immediate reach of the law or the beneficiary of strategic exemptions and a studious, state-tolerated blindness.

As elsewhere in the world, Mozambican miners probably used alcohol to help cope with work induced stress, or simply as a reasonably familiar lubricant to sustain social relationships in an overcrowded, potentially volatile, all-male and generally oppressive environment.

For much the same set of reasons, one imagines, recruits used the up train to smuggle in large quantities of cannabis for personal use in the compounds – yet another part of an age-old rural tradition bent to help meet the stress imposed by a brutal form of modern industrialisation. In the case of alcohol, however, the point is that nowhere else in the civilised world was the link between the producers of beer, wine or spirits and a mining industry spread over two neighbouring countries as closely and consciously fostered, or for so long a period, as it was on the Witwatersrand.

But, as importantly for our purposes here, we will never know the full cost in mental or physical terms that alcohol dependence or heavy use exacted directly on the men, and indirectly on the women and children, of the Sul do Save.

Nor is it always helpful to distinguish so clearly between the mental and physical manifestations of addiction, because they were often closely intertwined.

It is, for example, now well established that there is often a link between alcohol abuse and what today is regarded as post-traumatic stress disorder. In industrialising South Africa, the mining industry was party to a sustained attack on the characters, minds and bodies of African men.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners