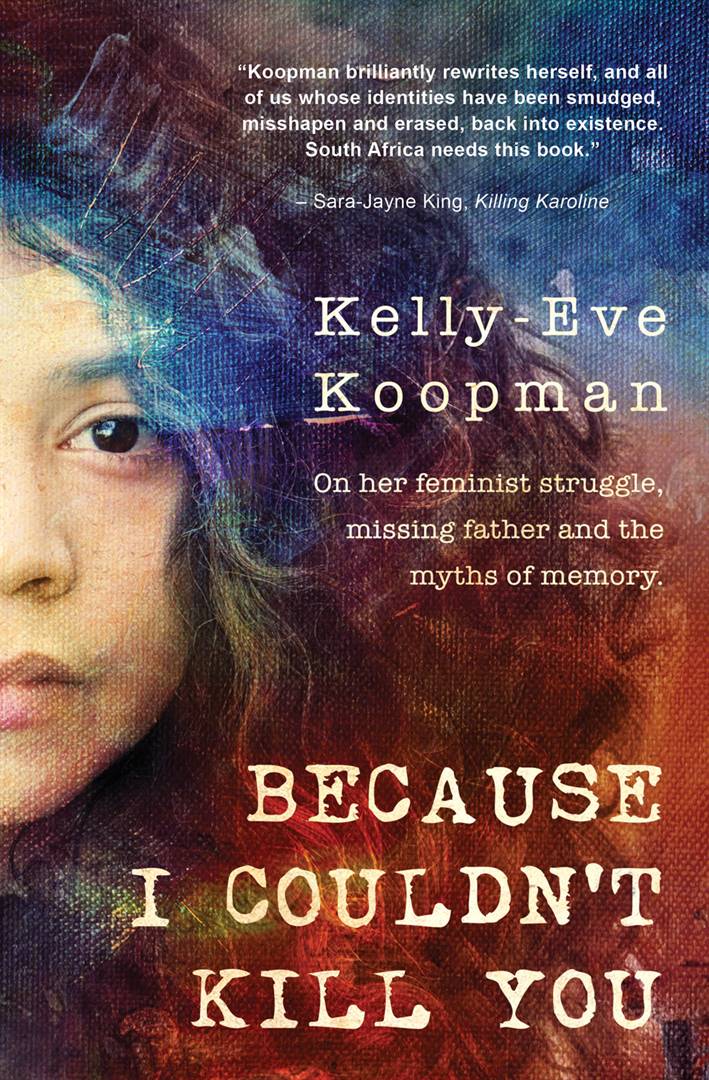

In this debut collection, feminist Kelly-Eve Koopman grapples with the complex beauty and brutality of the everyday as she struggles with her family legacy.

She tries unsuccessfully to forget her father – an embattled journalist and anti-apartheid activist, desperately mentally ill and expertly emotionally abusive, who has disappeared, leaving behind a wake of difficult memories.

In this extract, she speaks to her mother about her activism in the struggle against apartheid.

My mother wears a secret shade of red

My mother and I are lying next to each other in her bed. We’ve spent a lazy day napping, eating pancakes, watching cooking shows, talking about books.

My mother is slowly learning how to rest without feeling guilty about it.

Over the years, I have seldom seen her truly relax. To be fair, doing nothing was never a ready option for her.

She is a single mother who has supported three emotionally demanding children. She also has a doctorate and a master’s degree from Harvard.

My mother is beautiful, with an open oval face and a halo of beautifully greying natural curls; she has never worn even a smudge of make-up.

She has problems with her knees and ankles and so can only wear Green Cross pumps or Crocs.

She occupies a powerful position at a university and really enjoys her job.

She owns her own property and is smart with her finances, she gives incredibly generously and I know for a fact that she’s a mother/mentor figure to many of her students.

My mother is also an ex-con. Well, rather an ex political prisoner.

She’s wrapped up in a fuzzy pink nightgown. I’ve made her a cup of tea, which she says is delicious, the best she ever had. (My mother is incredibly liberal when praising others and very hard on herself.)

We’re chatting about the past.

Recently, I have been asking her all about my father and, in doing so, have erased the parts of her that existed before, beyond, after.

She is expansive and I have made her small by defining her by her relationship with a man. I suppose even in asking her about being imprisoned I am still attaching her value to her trauma.

But I want her to tell me, so I can honour her and her story, eclipsed by the men who would rather characterise women as the flowers of the revolution than its very roots.

We don’t know the stories of women in struggle with any kind of intimacy. We know the litanies of our male heroes, the mythologies of warriors.

But what happened outside the unmarked grave with the bloodstained underwear and the broken ribs of the woman cadre? Why does our history remain silent about them?

Is it because their stories are too messy, too difficult to hear?

Is it because we still want to pretend we do not know how these women were broken not only under the hands of the enemy but by their own comrades, treated as punching bags because, unlike the real enemy, they did not carry guns or, if they did, would not turn them on husbands and brothers?

Sons and daughters have a way of silencing and erasing our mothers in more intimate and loving ways than history and violence, but we erase them nonetheless.

For the first half of our lives we do not even use our mothers’ real names. They are not human, only ‘mommy’, defined by love for us and love for them, the ultimate symbiosis.

As I have grown older, I have wanted all access – to know it all, feel it all.

What was it like being pregnant, when did you first fall in love, did you ever have feelings for another woman? What was it like in prison?

By this time they have already learnt not to trust us, we who have fed off their bodies and ravaged their time and cannot be trusted with their personal intimacies.

The secret life of my mother will always be like this, the locked luxury drawer.

She is generous but cautious when she offers me things. And I have learned to be more gentle when I take.

My mother tells stories like I do, starting with the anecdotes, jumping around in structure, trying to piece together threads of moments, like playing Monopoly or singing in chorus the name of Shirley Gunn, 50-odd black women shouting the name of Shirley Gunn, an anomaly, this white woman of the MK locked alone, solitary in her prison cell with an endless loop of her tiny screaming child played over and over again to make her remember she is a woman, she is a mother, she has so many things that will be taken away from her.

My mother makes a point of dispelling any preconceived notion of activist, guns out, fists up – the violence, the drama, the glamour that my father oozed like a thick, hot musk.

She had been in and out of trouble with the police a couple of times, she tells me, but she was finally arrested and held after the Security Police came to her classroom where she taught at Kasselsvlei High School.

It was during the school strikes, she says: “We wanted to keep the kids in school even during the strikes, they weren’t safe on the streets, so some of us had what we called People’s Education.”

This was a retaliation against Bantu Education and a key component of the student struggles of the 1980s.

The strategy relied on teachers, workers, communities to co-develop a counter-hegemonic educational structure that would lay the foundation for students in the future South Africa.

This was what my mother believed in. And this is what she was doing when the boere invaded the school, brutalised some of the students and teachers, as was usual practice, declared her teaching materials treasonous and dragged her off to prison.

She laughed at one of the police officers who was almost moved to tears that she could possibly insult the brave South African troepies laying down their precious white lives for the nation, because of a poster on her wall that suggested that the border wars were an affront to freedom.

Whenever my mother speaks of her activism, she speaks of it by referring to her students, to those younger and more vulnerable than she was, although she was a young woman, younger than I am right now.

She was barely in her mid 20s, experiencing her first love, her first real job along with her first arrest and no doubt her first fears of death.

It was during the State of Emergency when political prisoners could be held without being charged and without a trial.

And of course the government was under no pressure to notify people’s families of the comings and goings and lives and deaths of prisoners.

My mother was rounded up with a male comrade, hosting a similar People’s Education session in his classroom, and another woman teacher.

A teacher who was not really political at the time but who my mom says attempted to protect some of the children at the school who were easy targets.

Many of them, suspected to be young radicals, had been mauled or killed by these tyrants in uniform.

When my mother speaks specifically about the trauma of this time, she does not speak about the prisons, or the raids or protests.

She speaks about all the funerals. The carrying of the coffins of children, and how she and other teachers linked arms to form a human chain at once holding back and holding on to swelling crowds of youth, screaming, crying, as more and more joined the crowds to the cemeteries.

Praying that a funeral wouldn’t turn into a bloodbath as the police force stood ready to shoot at the procession of crying, angry mourners.

She remembers this moment grimly, half leading, half corralling this crowd of mourning children, because my dad was there, she says, running up ahead. Taking a picture for the papers.

When she lets me in on these moments, I understand how their love must have worked, the importance of being present for each other’s tragedies and triumphs.

Extract taken from Because I Couldn’t Kill You by Kelly-Eve Koopman. Published by MFBooks Joburg. Available at all good bookstores. RRP: R240

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners