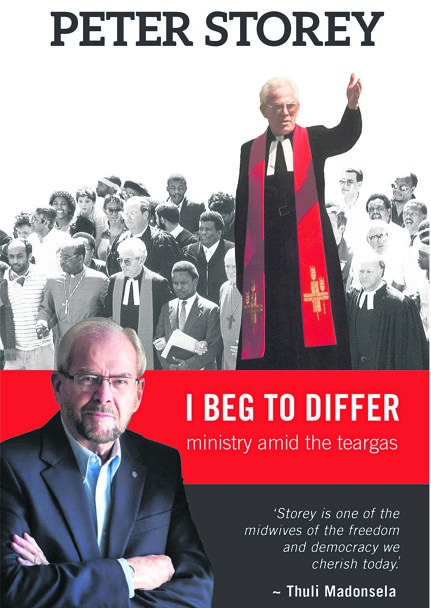

As a former bishop of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa, Peter Storey defied white prejudice enforced during the apartheid era.

In this edited extract from his book, I Beg to Differ, he speaks of his visits with Pan Africanist Congress leader Robert Sobukwe on Robben Island and how the time spent with Sobukwe affected him

I Beg to Differ by Peter Storey

Tafelberg Publishers

496 pages

R320

By the time I visited him, Robert Sobukwe had already earned the grudging respect of his gaolers.

My driver, a tough non-commissioned officer in his 50s, remarked that none of the baiting by bored young guards around the perimeter had succeeded in evoking a reaction from him.

“Every morning, this man comes out of his house dressed as if he is going off to work,” he said. “He is very dignified.”

As we approached the weathered hut, I wondered what kind of welcome I would receive. The SABC and the press had portrayed Sobukwe as a dangerous black nationalist with a hatred of whites.

Would he want to see me – a young white minister?

Sobukwe met me on the steps of his bungalow. I was immediately struck by his handsomely chiselled features and patrician bearing.

Tall and wiry, and dressed in neat slacks and a white shirt and tie, he offered me a guarded but polite welcome, inviting me inside as if this was his own home and I was a guest coming for tea.

The room we entered served as both bedroom and living space, with a neatly made bed, a simple bedside cabinet, a table and chair, and a small bookcase.

It was spartan but adequate.

Sobukwe gestured to the only chair and sat on the edge of the bed. Conversation was desultory at first. I knew he was sizing me up and didn’t blame him.

I said that many Methodists would be excited to know that one of our ministers had got to see him. We swapped names of mutual acquaintances and stories of Healdtown, the Methodist college both he and Nelson Mandela had attended.

It was the year that Reverend Seth Mokitimi was about to be elected the first black president of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa, and he spoke admiringly of Mokitimi’s influence as a chaplain and housemaster at Healdtown.

Our conversation soon warmed and, after that, each time I came to the island we were able to have about 30 minutes together.

He had a consistent aura of calm about him, sucking contentedly on his pipe while we talked. He chose his words carefully, spoke quietly and had a gentle sense of humour.

Our discussions were perforce circumscribed, always in the presence of the guard, who stood near the door, pretending to be uninterested. Even so, it was possible to engage something of the depth and breadth of his thinking.

His Christian faith was informed by wide reading and it was quite clear that he saw his political activism as an extension of his spirituality.

He was excited by Alan Walker’s 1963 preaching campaign in our country, and the furore around Walker’s challenge to the apartheid state.

This was the kind of witness he expected of his own church leaders, only to be frequently disappointed.

He was impressed when I told him I was hoping to go and work under Walker for a year.

I was later permitted to bring him a few theological books, and included all of Walker’s writings.

Both of us being pipe-smokers, I could also bring his favourite tobacco and we used to chuckle that both this Methodist minister and lay preacher had a taste for Three Nuns blend.

Robert Sobukwe impacted me very powerfully. For all my contact with black South Africans, here, for the first time, I was engaging with somebody risking all for the liberation of his people.

The calibre of this man, the cruel waste of his gifts and the silence of most South African Christians around his incarceration, touched me to anger.

On his part, he always expressed genuine appreciation of our times together, but even though I was one of the only people, apart from his captors, ever permitted to see him, I sensed that he would never put too much trust in these visits.

Why should he place faith in this white man, any more than any other? I always came away angered and ashamed.

Once, when leaving him, I expressed my shame that I could depart the island so freely, leaving him a prisoner. His response was quick. Gesturing toward Cape Town, with its Houses of Parliament occupied by his tormentors, he said: “I’m not the prisoner, Peter – they are.”

Every visit made it more evident to me why the apartheid government feared Robert Sobukwe so much, but the years of virtual solitary confinement later began to break even this man.

Benjamin Pogrund, biographer and close friend of Sobukwe, tells that, by 1969, he was near a breakdown.

“The government took fright and hastily sent him off the island, to banishment in Kimberley, which included house arrest and bannings.” Sobukwe qualified as an attorney and practised law in Kimberley, enjoying the admiration of the local people there.

Activist Joe Seremane spoke with wonder about the “Prof’s” magnanimity, telling of how, when passing a police van with a flat wheel, Sobukwe stopped to help the white cops fit a spare.

In October 1975, 12 years after our first meeting on the island, I had a last visit with him in his Kimberley home.

A security police car was parked outside as usual, indicating that he was still being watched.

With John Rees, then general secretary of the SA Council of Churches, who had helped support Sobukwe’s family for a number of years, I had an hour with him.

The flame still burned within him, perhaps with an even brighter incandescence. We prayed together and parted.

Two years later, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe was diagnosed with lung cancer and died in 1978 at the age of 54.

Spiritually, Robert had travelled a bumpy journey.

After I left the island, the chaplaincy was taken over by the Reverend Theo Kotze, who was later to become Beyers Naudé’s right-hand man in the Christian Institute.

Theo was a seasoned minister, and could offer far more to this remarkable man than I.

After Theo, however, there was an encounter with a very different, legalistic religious approach, which put Robert off chaplains for good. I believe that he refused further ministry.

I was also the first chaplain to Nelson Mandela and his fellow Rivonia Trialists.

When they arrived in mid-1964, they entered a period of extreme hardship and very tough manual labour in the island’s lime quarry.

I, of course, saw nothing of this, because Sunday was the one day of rest granted them.

They were incarcerated in the squat, Maximum Security B Section, with its ugly watchtowers, cold grey passages and grey-painted barred doors.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners